Compose in Darkness

- By Michael Thurston

I was with friends at a conference in Britain when I got the news. “Heaney has died,” read Emily’s text. “So sad.” And as others at the conference heard over the course of the day, the reaction was similar: so sad. A former student who had studied the poet’s work with me and had written an essay on his work emailed to say that it felt as though a mutual friend of ours had died. My daughter posted as her Facebook status update the closing lines of “Digging”: “Between my finger and my thumb the squat pen rests, snug as a gun. I’ll dig with it.”

Heaney himself was at a conference—of poets—when he received word that his cousin, Colum McCann, had been murdered, another in the long line of Northern Ireland’s victims of sectarian violence. In “The Strand at Lough Beg,” Heaney’s elegy for his cousin, the poet imagines himself washing from McCann’s face the roadside mud he had fallen in when shot. Alluding to the scene in Dante’s Purgatorio in which Virgil cleans the filth of the Inferno from the poet’s face, Heaney writes that he would plait green scapulars from the reeds around Lough Beg, a place familiar to the cousins from childhood, and would give him back to nature, give him up to God.

Heaney was a brilliant elegist, and central to his brilliance was his ability to weave, as he does in the green scapulars of “The Strand at Lough Beg,” strands of personal experience, literary allusion, and historical significance, so that any individual death might be seen to ramify in numerous and complex ways. It is worth noting how Heaney’s elegiac practice is at once in and quite distinct from the main currents of the elegy in English poetry (and by “English” here I mean the language, not the nation). Typically, the elegy moves from the fact of loss through the heightening of the value and importance of the dead and, finally, to a shift of attention from the lost figure to a new one, a site in which poet and reader can invest the love whose object has disappeared. Heaney’s elegies register loss and remember attachment, but they do so in ways that complicate the acceptance of a new object. This is, in part, because the loved one often represents realities in which the poet continues to be enmeshed, whether the realities of family in his elegy for a younger brother who died while the poet was away at school, or those of nation, as in “Casualty,” his elegy for an acquaintance killed in an I.R.A. bombing, or those of poetry itself, as in his elegies for the likes of Robert Lowell and Joseph Brodsky. In “Clearances,” the sonnet sequence that elegizes his mother, the poet captures this difficulty with a peculiar and moving acuteness, likening his mother’s death to the disappearance of a chestnut tree that had been cut down, seeing it as an absence that cannot be filled, a hole whose real meaning is that we can never be made whole.

Brilliant as he was, Heaney was also among the most laceratingly self-critical poets of the twentieth century. In “Station Island,” a poem filled with Dantean scenes of confrontation between the poet and the dead, Heaney has the cousin he elegized launch a vituperative attack precisely on the aesthetic and spiritual consolations the poet himself had offered in “The Strand at Lough Beg.” To wash the bodies created by history in the dews and rushes of literature would be to deny the realities of blood and mud. In “Punishment,” a poem provoked by the bog-preserved body of a Neolithic woman who had been blindfolded and strangled, Heaney balances his desire to love and protect the woman (and, by extension, the young Catholic women in Northern Ireland who were humiliated for fraternizing with British soldiers) with his admission that he is implicated in the tribal outrage that produces such violence. Much of his strongest work of the 1970s and 1980s aimed to think through the poet’s position in a society riven by political and religious division, to parse the poet’s responsibility to his community and his moment, to set these against those he bears toward his art. His “Glanmore Sonnets,” written after Heaney decided to move with his family from Northern Ireland to the Republic of Ireland, weighs the martial bagpipes and slughorn against the songs of self, love, family, and nature that he feels compelled to sing. That balance was an impossible one to strike, but Heaney’s efforts, his scrupulous and self-critical and open and continual work at it, produced some of the century’s most powerful verse.

That can’t be enough, though. A difficult challenge and the visible effort of rising to it can explain neither the impact of Heaney’s work nor the profound sense of loss many of his readers have felt in the days since his death. Perhaps we take his death so hard because both man and poet were so warm and generous. In person, in print, in conversation and in poems, Heaney welcomed approach and held a curious and open mien toward the world. His essays, like his elegies, made clear the depth with which he loved (especially poets, especially Dante, but also a long list of others, from all over the world and throughout literary history). And it was not only people and poets and poems that the man clearly loved. It was words. What wonderful words he found and framed, what wonder he showed in how the words worked. I saw an actual gleam in his eye once when he talked about words like “glaur” and “fangle,” and the love of language is palpable in his poems, from the early “Anahorish” and “Bruagh” to his translations of Beowulf and Sophocles. It is a big loss: there are so few poets with his combination of ambition (to take on the very largest, hardest questions), humility (to recognize the shortcomings in his resolutions of these problems), and sheer linguistic, rhetorical, and poetic ability.

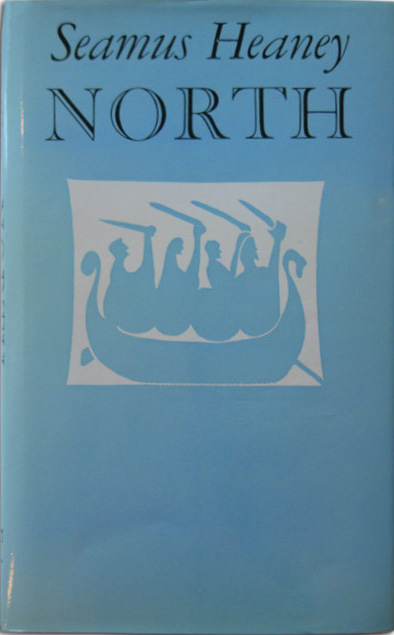

Many people this weekend have, like my daughter, like my spouse, like my friends, circulated their own favorite lines of Heaney’s. I’ll join that chorus. In the title poem of North, a volume wracked with the pressures of its mid-1970s moment, Heaney walks along the beach and hears, amidst the noise of the Atlantic, the tongue of the Viking long ship speaking to him, speaking directly to his crisis and dilemma. Rather than take sides, this voice from the past urges the poet to turn to language, to find in it the means of keeping connection with the world:

‘Lie down

in the word-hoard, burrow

the coil and gleam

of your furrowed brain.

Compose in darkness.

Expect aurora borealis

in the long foray

but no cascade of light.

Keep your eye clear

as the bleb of the icicle,

trust the feel of what nubbed treasure

your hands have known.’