Stories We Tell Ourselves about Ourselves

- By Jim Hicks

“Stories we tell ourselves about ourselves”… I’ve always liked that phrase, from the anthropologist Clifford Geertz. Even more so because these days I regularly come across suggestions that the self itself may be nothing but story. “Nothing but” – I must insist – is a far cry from “just” or “merely.” Readers of MR, or any serious readers at all, ought to read this first qualifier as a lever, and start their heavy lifting. If identity is nothing but narrative, we’d all better think seriously about what stories we’re telling, and why.

In late October, the Mass Review will deliver a special double issue called Casualty, filled with reflections of just this sort. A decade after the attacks in New York and D.C., and after the start of the U.S. war in Afghanistan, our goal is to remind folks that wars don’t end just because we stop paying attention. The intent of this volume is to document – through art, fiction, poetry, and engaged nonfiction – the ongoing toll of this war and others on minds and bodies that have seen combat, or suffered from it.

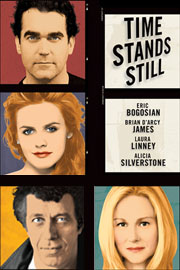

Maybe it’s just me, but I think most war stories in U.S. today are decidedly different. Take, for example, Donald Margulies’ Time Stands Still, a very well-made play about the lives of a couple of war reporters, a photographer and a writer. As the play opens, both are back from Afghanistan, or Iraq, or some damned place: the writer returned traumatized after witnessing a particularly gruesome bombing; his partner limps in from a military hospital, bearing the scars of an I.E.D. attack. When I saw it last winter in New York, the play was masterfully staged, and the cast was top-shelf (Laura Linney, Brian d’Arcy James, Eric Bogosian, and Alicia Silverstone). The script no doubt deserves its comparisons to the work of David Hare. So why was I furious for weeks? Why do I still feel it’s worth a rant?

different. Take, for example, Donald Margulies’ Time Stands Still, a very well-made play about the lives of a couple of war reporters, a photographer and a writer. As the play opens, both are back from Afghanistan, or Iraq, or some damned place: the writer returned traumatized after witnessing a particularly gruesome bombing; his partner limps in from a military hospital, bearing the scars of an I.E.D. attack. When I saw it last winter in New York, the play was masterfully staged, and the cast was top-shelf (Laura Linney, Brian d’Arcy James, Eric Bogosian, and Alicia Silverstone). The script no doubt deserves its comparisons to the work of David Hare. So why was I furious for weeks? Why do I still feel it’s worth a rant?

Here’s why: The play is a pitch for isolationism, that form of conceptual blindness whick belies U.S. political realities. The moral center of Margulies’ story is the Alicia Silverstone character, a ditzy youngster who waxes lyrical about stay-at-home momming, and complains about bummer photographers who show us bodies in pain – whether in war or nature. In this drama, civilian casualties are a lesser form of the suffering incarnated by an baby elephant separated from its mother. (Because suffering is what happens in Africa, don’t you know, and, though not species specific, it is at least exotic and distant.) By the play’s end, we know what to think and do: the journalist has left the photographer, and has found himself a family. Only Linney’s character, the photographer, will return to the front, and we know why. She’s addicted to adrenalin, and addicts like her are either criminals or candidates for rehab, whatever. They certainly aren’t like us.

I realize that, if you haven’t seen it, this tirade may seem to be shooting up a straw man. The audience for serious theater in NYC or LA is even less than the percent or two of our nation’s families that supply our war efforts. But never fear, you do know this story. It’s also the bottom line of the only film about Iraq that an audience did come out for – Kathryn Bigelow and Mark Boal’s enthralling action pic, The Hurt Locker. What did those seven Oscars enshrine, after all? A damn good time, certainly; a tremendous performance by Jeremy Renner, no doubt. But also a punch line, one which tells us just what we want to hear. That boy is only home in a war zone. In short, he’s majorly fucked up.

a straw man. The audience for serious theater in NYC or LA is even less than the percent or two of our nation’s families that supply our war efforts. But never fear, you do know this story. It’s also the bottom line of the only film about Iraq that an audience did come out for – Kathryn Bigelow and Mark Boal’s enthralling action pic, The Hurt Locker. What did those seven Oscars enshrine, after all? A damn good time, certainly; a tremendous performance by Jeremy Renner, no doubt. But also a punch line, one which tells us just what we want to hear. That boy is only home in a war zone. In short, he’s majorly fucked up.

As a story we tell, this one certainly lets us off the hook. War gets subcontracted to a subclass of sickos, people that we may understand and sympathize with, but only insofar as they’re nothing like us. Nothing like the citizens, that is, of a country that has military bases in well over a hundred other countries, not to mention hundreds here at home. This country’s spending on what we usually call “defense,” at last reckoning, came in at roughly forty-three percent of the entire planet’s military budget. And is it possible that we’ve forgotten who started these wars?

Isolationism is a mindset that enables our government to do whatever, so long as it isn’t our bodies that suffer. And if we want to talk addiction, well then, it certainly isn’t as if a few bad apples have somehow hijacked our history. The addiction, if there is one, is national.

How many tickets would that sell?