Carl Hancock Rux: Marking History, Juneteenth 2021 at Lincoln Center

- By Ifa Bayeza

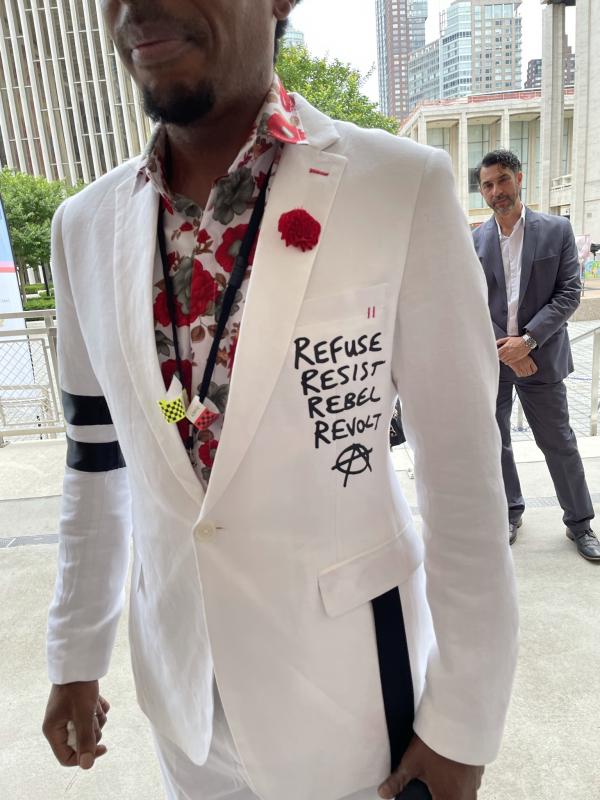

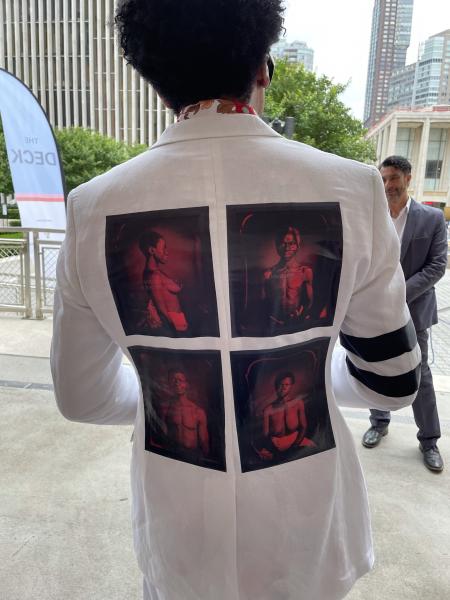

Director and curator Carl Hancock Rux. Photographer Ifa Bayeza.

Director and curator Carl Hancock Rux. Photographer Ifa Bayeza.

Carl Hancock Rux is a tour de force. We first met at a Theatre Communications Guild panel in 1998. That day, he invited me to his concert performance which launched Joe’s Pub at the Public Theater on October 16. I did attend that day, and I’ve been following Carl’s creative career ever since.

That first event was a concert reading of his opera, Blackamoor Angel, about the Sub-Saharan African Angelo Soliman, who in 1727 was kidnapped and enslaved at the age of eight and brought to Vienna, Austria. There he rose in stature to become tutor and chamberlain to princes, colleague to Mozart and Haydn, and confidante of the emperor. Yet, upon his death, his skin was flayed from his flesh and stuffed for display among the other African “beasts” in the imperial natural history collection, where it remained until destroyed by fire fifty years later.[1]

Elements emblematic of Rux’s later style were evident in the opera’s embryonic performance. As librettist and leader, he had assembled a powerful collaborative team, including composer Deirdre Murray, director Karin Coonrod, a full chamber orchestra with a chorus of powerful singers. The story of Soliman’s anguished history was conveyed with a sonorous lyricism that revealed a mind equally intellectual and poetic, as well as one keenly aware of environment. In this case, the loud cacophony and excitement of a club opening seemed to evoke the atmosphere surrounding Rux’s woeful protagonist in both his glory and ignominy. The space became part of the drama.

My next encounter was his musing on James Baldwin for New York City’s 2014 Year of James Baldwin, a celebration of the pioneering writer. Rux’s tribute imagined an encounter between Baldwin and iconic musical genius Dinah Washington, played magnificently by Marcelle Davies-Lashley. A byzantine crystal chandelier lay on the floor while, at the nadir of her career, the famed blues singer talked to her reflection in her backstage dressing-room mirror. Then, in a documentary video clip of a contentious interview between Baldwin and an assaultive interlocutor, Baldwin riddled every question in a percussive, high tenor staccato, precise as artillery. Interwoven were scenes with prose spoken in Rux’s hypnotic baritone, delivered with his signature stillness. While the parts remain nebulous in memory, the impression of the whole lingers still.

Since that time, the two of us have had numerous collaborative adventures. On the eve of the publication of my novel Some Sing, Some Cry, co-authored with my sister Ntozake Shange, Ntozake and I gathered some friends to read sections of the book in her Brooklyn garden. Rux read a passage of mine. Upon discovering that a jolly bachelor party descends into a gang rape of the house maid, Rux expertly shifted his delivery with such profound abruptness, it took one’s breath. A few years later, as Distinguished Visiting Artist at Brown University, I invited him to direct two of my plays, String Theory and Welcome to Wandaland. More recently, in 2018, when I was Resident Artist in New Iberia, Louisiana, Rux came down to help mount my musical, Bunk Johnson. . .a blues poem, which made its debut the week after my sister died. Given the circumstances, it was the last place I wanted to be, but so many people were depending on me, I powered through, learning how to swallow my pain and exhale joy. That was Bunk’s story and mine, too, that week. Rux with his electric energy and insanely funny antics off-stage—so different from the gravitas of his stage persona—kept me buoyant. These prefatory remarks should serve as full disclosure: when it comes to Carl Hancock Rux, I am both a friend and fan.

It was with great anticipation that I made plans to see his production celebrating Juneteenth on Saturday, June 19, 2021 at New York City’s Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. By divine serendipity, only two days before, the date had just been declared a federal holiday and signed into law by President Biden. The declaration was sprung upon the nation so fast that there was little time to absorb the significance, let alone the facts behind the date: the final triumph of the Union in the Civil War, the acknowledgement, if not acceptance, of defeat by the rebellious Confederacy, and, in the “land of the free,” the liberation of four million people from state-sanctioned human bondage.

While the state of Louisiana and parts of South Carolina had been under Union occupation since 1862 and ’63, respectively, and though Robert E. Lee had signed the treaty of surrender to General Grant at Appomattox in April 1865, Texas—long cultivated as a laboratory for the slavocracy’s imperial ambition—was the last hold-out. Desperately clinging to their dream and “property,” slaveholders aplenty from Louisiana to Arkansas had fled with their caravans and coffles of Africans to the far reaches of the state. On the island of Galveston, just off the Gulf Coast, Union General Gordon Granger got around to announcing our emancipation to a small cluster of Black folk on June 19, 1865, two months after the war purportedly was over. On the balcony of the Alton Hotel, he read from a handwritten note, just ninety-three words:

The people are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, become that between employer and hired labor. The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.[2]

Banished to the post by General Grant, who disliked him, Granger seemed to have no grasp of the moment’s significance. While there is no record of the crowd’s response, such is the poetry of Black folk that someone put our jubilation into a contraction—Juneteenth! Ever since, African Americans have marked the day with celebration. First in Texas and then nationally, it has become a date of memory—collective joy—when we as a people may commemorate both triumph and deliverance, and if a bit qualified, the declaration of our independence and “absolute equality.” To mark the date, Carl Hancock Rux’s Juneteenth exposition at Mr. Lincoln’s Center was a Happening, in all senses of the word: a multimedia, multi-genre performance, traveling across space, time, and history.

Prelude

As I arrived, a medley of pre-show guests gathered under a huge white tent, pitched on the 62nd Street side of the Center. Though the sky threatened rain, Lincoln Center Executive Director and CEO Henry Timms, standing at the entrance, greeted everyone with elation. Rux’s presentation was to be part of the re-envisioning of Lincoln Center, democratizing the vast concrete plaza as the new public square. The repurposed environment, he explained, would include a voting center/vaccine center and the newly created green space—which, even under the ominous, greying skies, was filled with young families and children frolicking on the man-made hills. The Juneteenth program was one of Lincoln Center’s first public events, post-Covid, and though the attendance would be limited, the sense of release and relief defied even the few protean sprinkles. Everyone carried an umbrella tucked away. We weren’t going to miss this.

In short order, Rux appeared, wearing a white summer tuxedo of his own design, with a red and black floral shirt, the pants Bermuda-length—Frederick Douglass meets Patrick Kelly. (A characteristic of Mabou Mines, where Rux has been a long-standing member: when the director arrives, the show begins.) His tailored white jacket’s breast pocket was emblazoned with the words “REFUSE, RESIST, REBEL, REVOLT,” and wound round the jacket sleeve were double black armbands of mourning. On the back of the jacket were silkscreened images of a quartet of photos from Carrie Mae Weems’s 1995 exhibition, mounted in response to “Hidden Witness,” the Getty Museum exhibition showcasing antebellum images from their archives of Black lives. Among her creations were four re-treated photographs originally made in Columbia, South Carolina in 1850 at the behest of Louis Agassiz, the celebrated father of American natural science. They are among the earliest known photographs of Southern slaves. In his dogged effort to disprove the fundamental equality of man, Agassiz had the four subjects stripped naked and posed, vulnerable and powerless. Weems overlays each image with plexiglass tinted a dense, fresh-blood red.

Director and curator Carl Hancock Rux and guest at

pre-show reception. Photographer Ifa Bayeza.

As Rux moved about greeting guests—Carrie Mae, herself, Lynn Nottage (who contributed lyrics for the event), colleagues from Mabou Mines—this quartet of Africans silkscreened to Rux’s back in that field of white, stood as sentinels, both shielding the wearer and silently alarming and assaulting viewers with their dignity, sorrow, and rage: their humiliation brimming from eyes glazed with tears.

His shoes spoke of another era: Platform, patent-leather with crepe ties, they were Cotton-Club-Cab-Calloway-Josephine dancerly! The pre-show costume was an overture, a condensed highlight of what was to come. The pain, the joy, Black taps and Taps.

A stunning young African-American couple arrived late to the gathering, dressed in matching white quilted fabric: the woman in a flowing sheath with an irregular hem cut on the bias, and the man in loose knee britches and tunic, their hair African crowns of natural spirals. They turned out to be our guides for the evening: Jamel Gaines as “Emansuh Patience, an escaped slave man” and Valerie Louisey as an "Anonymous Woman.” Later joined by veteran actor Stephanie Berry, playing "Ain'tGotNuhPatience,” the three together, through dance, gesture, and improvised prompting, would usher us through the multi-tiered event.

There was no printed program. The evening would demand our undivided attention without distracted glances at the page. Background information provided later allowed me to contextualize what I had experienced. In the moment, though, the absence of a program was part of the event. Untethered, I became kin to thousands of my forebears, freeing themselves by fleeing toward the Union lines. Largely nonliterate, for centuries as fugitives, they had made their way by reliance on the signs in quilts and nature, the coded lyrics of a song, patterns in the sky. Could they read the stars on a grey night such as this?

The evening was to be a sort of “station drama,” most often associated with both the medieval mystery play and German expressionist theatre. The clandestine stops of the Underground Railroad, commonly referred to as “stations,” also came to mind, as random parties of the audience moved sometimes warily from space to space, unsure of what was to come.

Rux’s work has enjoyed an ever-shifting traveling band of extraordinary collaborators. The Juneteenth Project was comprised of an ensemble of about fifteen performers and a dozen crew members, among them, in addition to Nottage, Rhythm & Blues Foundation Hall of Famer Nona Hendryx (better known now for her new age experimentation), singer-songwriter Toshi Reagon, and again Marcelle Davies-Lashley. Rux conceived the event and served as curator, researcher, and director. The evening, however, seemed a creative collective. Each of the component parts had a distinct flavor and scale. All possessed the vivid and intense sounds and colors of Blackness in simultaneous mourning and celebration.

The performance spread over three distinct settings across the center’s vast campus. One setting to the north would occupy the Hearst Plaza and the Olympic-size Paul MiIlstein Pool. Another performance area would run alongside 62nd Street and abut Damrosch Park. In front of the opera house on the walkway connecting the north and south campus sat a giant trapezoidal platform at least a story-and-a-half tall.

Constructed by Diane Smith, the tower was skirted with undulating waves of ruffled paper that spilled onto the granite at its base. Atop sat the torso of a diminutive human, Helga Davis as “Statue of Liberty? (One Tall Angel),” her exquisite ebony face framed by the twilight and a very animated cerulean wig. She completed the ensemble with mismatched red and white evening gloves. In front of the opera house, she was delivering an absurdist Dada-inspired aria of the National Anthem. Beckoned by “Aintgotnuh Patience,” I proceeded to the next installation.

Station 1: Crossing the Water: Combahee

As if entering a history that had already begun, I was swept along into a scene in progress. I angled my way through the staggered audience gathered round the Paul Millstein Pool, now transformed into a Baptismal threshold. Three primordial figures, the Combahee River Angels, Nona Hendryx, Kimberly Nicole, and Marcelle Lashley, from the far-side, waded across the waters, singing Nottage’s elliptical lyrics, “The night is cold, but the flow is deep, tell me what’s on the other side, what’s on the other side of this desire. . .” Intoned by Rux’s trio, Nottage’s lyrics and the melody by Vernon Reid and Hendryx were possessed equally of the hope and apprehension within the desperate thirst for freedom … knowing not what it was, only what it was not:

Water. Clear Water. Tranquil Water. Healing

Water. Healing healing ‘fore we drown.

I’m trembling, trembling yet I’m still

I’m hungering, hungering yet I’m full Tell me,

What’s on the other side of this desire?

Kimberly Nichole, Nona Hendryx, and Marcelle Davies-Lashley as River Angels with

musician/composer Vernon Reid. Photographer Sachyn Mital, Courtesy of Lincoln Center.

As they sang, the women glided through the knee-deep water, coming together then drifting apart, always moving forward and beseeching:

Water calm. Long enough for me to get there. Water calm long enough for me to get there.

Combahee (pronounced kŭm-bē′ or kŭm′bē) is the name of the river which, from St. Helena’s Sound off the coast of South Carolina, makes its jagged way into the interior of the state. Rux recounted to me how in June, 1861, Harriet Tubman commanded a party of about 150 colored Union troops travelling up the river in three gunboats. There they lay siege to the numerous rice and cotton plantations, representing the rebellious Confederate nation’s “old money.” Upon hearing that Union forces were near, slaves headed toward the boats en masse, running toward the water and their liberators. “They came down every road, across every field, dressed just as they were. . .Women with children clinging to their necks, hanging onto their dresses, or running behind, but all rushed at full speed for Lincoln’s gun-boats,” and toward the siren call of the Combahee River Angels.[3]

Their voices now echoed off the granite, glass and water, creating a cathedral-like tintinnabulation, so I couldn’t quite hear Nottage’s elemental yet elegant words, but that too was part of the textured experience. We are never quite able to hear our song, or see our noble place in the story of this nation’s promise. As the lyrics say “we feel it, we can’t see it.”

The atonal chords and improvised outbursts recalled numerous Negro Spirituals and their coded messages of liberation. “Water, water, water, water,” they chanted in tight harmonies, evoking the wails of the Middle Passage. “Water, water, water, water,” summoning the will to brave the perilous threshold between slave and free. Chorale arrangements by Nona Hendryx, simultaneously muscular and ethereal, like water itself, drew you in. As the three singers seemed to glide against the currents generated by their own bodies, the cadence of their song swirled round us.

The costumes, designed by Dianne Smith, were constructed of paper. Each angel was adorned in a distinct, earthen-toned garment, a taupe-sienna wash of water colors, like the russet clay of the Georgia plains or the muddy waters of the Mississippi or the crests of the Red Sea. The dresses blended with the brown-skinned hues of the singers’ bare shoulders and faces, bejeweled in astral make-up by Christina Jones.

With Hendryx’s hydra-sculpted wig (designed by Rux and styled by Jhetti Rose) and Lashley’s glistening bald head, the trio seemed visitors from another plane—angels, indeed. Smith chose in the texture and detail of each costume to accent cross-currents of time. Each sculpted and fitted papier-mâché corset was matched with a scalloped skirt of unique design. The hems seemed to hover, drag, and submerge by their own will. Ms. Nicole’s fluttered just above the surface like a waterlily:

Water. Cold. Water. Angry.

Water. Pulling Water. Pulling Pulling us down.

Water. Water.

Water. Water.

Bits of the costumes occasionally floated away. I was reminded of Mose Wright in The Ballad of Emmett Till, our Utnapishtim. “All the time swept away, swept away. swept away. My people, my people, all the time swept away. Bound to the land, bound to each other, all the time swept away.”[4] Black folk have been bound by paper the setting seemed to say, our humanity trapped within ledgers, inventories, codes, bills of sale, judgments, rules, laws. The depth of deception and obfuscation of our histories manifest before me even as the voices in the wind rang out, it would not always be so. . .

The river’s wide The shore is steep I can’t hear you.

But, I feel you next to me. I feel you next to me.

Vernon Reid and Nona Hendryx. Costume designer Diane Smith.

Photographer Sachyn Mital. Courtesy of Lincoln Center.

Combahee was the name of a people, now extinct, a people who had once roamed that land, crossed that river, named it; the meaning is now lost. Only the beauty of the sound remains. . .

I could have stood there ruminating for ages, but as the River Angels neared our shore, “Anonymous Woman” lured me back to the installation I had initially passed. "If you wish to avoid capture, take The Drunkard’s Path," she seemed to say. "Do not travel in a straight line." Onto the next scene and movement, an exercise in history repeating itself.

Station 2: Statue of Liberty? One Tall Angel

“Anonymous Woman” delivered me to the “Statue of Liberty? One Tall Angel,” played by Helga Davis. She was still singing! A statue of liberty? How can one be both, a Statue and Liberty? Was the platform a foundation or a prison? Was she a gift from Paris or Paris Burning? Still resting in the reverie of the baptismal waters, I wasn’t prepared for the jolt of her jagged satire or the unsettling, unforeseen jostling and manipulation of speech (even though that is one of Rux’s trademarks.)

As my audience compatriots and I craned our necks to fully view Liberty’s wild gesticulations, at the base of the platform Jamel Gaines, as “Emansuh Patience,” calmly translated as if he were an ASL interpreter. His languid minimalist movements were a complete contrast to the physical onomatopoeia, fractured language, and absurd disproportion above us. As Black folk have so often done, Rux was employing the satiric mechanisms of humor to treat the insane pathology of race still afflicting our nation. His directorial hand was evident in the deliberately discordant alterations of pitch and rhythm, achieved through interjected, casual asides. The spoken words were pronounced with idiosyncratic detonation of odd syllables, while the sung parts were belted glissandos from a contralto’s high C to baritone D, the volume from murmuring to deafening. Still, like the occasional manic episode of a schizophrenic, it made sense.

Our experience of this pathology of race seems to have no beginning and no end, a recitative of constant interruption and repetition. Modulating every decade to a different key, forever shape-shifting, it is still grounded, bound to our heritage. I found myself wanting to escape the stridency, although that was its purpose. Davis’ absurdist improvised rift on the “Star-Spangled Banner” was subterfuge, uprooting another classic presumption of the American experience. This “Statue” with her disruptive “Liberty,” was free to say whatever the hell she wanted, but stuck there. As this was an exercise in the exploration of liberty, I prepared to take mine.

Helga Davis as “Statue of Liberty?” and Jamel Gaines as

“Emansuh Patience.” Photographer Ifa Bayeza.

Then I noticed that Gaines’s gestures were flat, not beautifully animated as I have seen in other signed performances, such as the work recently displayed at Public Theater‘s production of for colored girls. . . .I realized that Gaines wasn’t actually signing at all, but doing what seemed to be a faux ASL. The choice seemed disrespectful and, at best, in poor taste. While one might argue, so was slavery, this addition wound up being the only disappointing note in my experience that evening.

Gaines’s comedic repartee seemed a missed opportunity to interject some sobriety into an otherwise comedic scene, the point of which was arrived at rather quickly, and scant use of Gaines’s noted talent as a solo dancer and choreographer. I considered how Black Codes in the Confederate slave labor states had forbidden that any form of literacy be allowed among the enslaved. Veteran actress and scholar Tonea Stewart—best known to the masses as Mama in “In the Heat of the Night,” and a matriarch to hundreds of young Black actors—tells the story of her grandfather, who had been enslaved and who was still among the living when she was a child. He recounted to her how, in his youth as late as 1864, for daring to learn his letters, he had been blinded with a molten sword pressed across his eyes.

I find with this next half-generation behind me, the progeny of George Wolfe’s Colored Museum, efforts to self-empower through shock irreverence; however, I am not one so willing to play light with that depth of pain.

What an actual ASL interpreter might have made of that moment! There are many excellent, authoritative Black signers whose choreographic aesthetic and movement would have borne witness to a real dialogue instead of a faux one. Imagine the language of gesture going up against the language of words, laws, rules, and seductive songs of celebration. The image of someone speaking without sound, standing up to the loud-mouthed structure of slavery, the frustration at not being able to communicate, memorialize, or make permanent our truths, would have lent much to Rux’s metaphoric landscape, and as an authentic signer, much to Timm’s desired commitment to maximum inclusion.

I left that station agitated, knowing that, too, was energy which could be put to use, a necessary ingredient to “Refuse, Resist, Rebel, Revolt.”

Station 3: The Voice-Over

I wandered to the concert seating area in the South Plaza. Arranged in staggered pairs of chairs, the set-up could accommodate about two hundred. Small pockets of audience had already collected. A few had taken their seats. I wiped my rain-speckled chair with a tissue and got my umbrella handy. The audience was adult, generationally diverse, of mixed race and gender identity, coupled for the most part like the chairs. There were no children. Because of the rain, I suppose, the prep-work was still in progress. I didn’t notice until that moment that, besides composer, musician Vernon Reid and Gaines, the performers were all women, another nod perhaps to a shift in our understanding of power and the interconnected struggle of people of color and women.

The stage was empty. As the audience trickled in and we awaited Toshi Reagon and her band, BIGLovely, an audio recording played faintly in the distance, the voices drifting overhead. Rux, the director, curator, and researcher who had conceived the event, had also taken an apparently minor performance role for himself: a pre-recorded voice-over with Martha Redbone, that looped as the audience gathered. Playing a “little girl,” Redbone recited Lincoln’s original and full Emancipation Proclamation with a voice only the child’s parents could enjoy. This was intentional agit-prop, mocking every bad school assembly one ever attended (though none of mine ever included that magnificent transformational document). Redbone’s declamation was followed by a string of archived voices from the American past, in point and counterpoint, among them, Ayn Rand, James Baldwin, and Lyndon Johnson, as well as subjects from the 1930s WPA slave narrative project, some of the last living testaments.

And then came Rux’s tome poem, spoken in a soft, unmodulated baritone, audible only to those who chose to hear, the logos. Marking time, he mused on the irony of our having to celebrate a holiday that marks a delay:

The Emancipation Proclamation

did not prevent the lynchings

or stop Black Wall Street

from burning to the ground

or save the lives of the Scottsboro Boys

convicted

I mean convicted

who were convicted

of raping a woman

in a boxcar.

It didn’t

It didn’t

It didn’t

stand in the way

of bullets hurled at

Medgar Evers

or Malcolm X

or Martin Luther King, Jr.

resulting in at least

125 riots throughout the country

and

General Order #3

did not prevent

the Red Summer of 1919

during which

white supremist terrorism

and racial riots

took place in more

than three dozen cities

across the United States

as well as in one rural county

in Arkansas

nor did it prevent

the Red Summer of 1964

when racial tensions in Harlem

provoked serious racial disturbances

in more than

six major cities throughout

the United States.

It didn’t

save Billie Holiday’s life

or allow her to sing

the first protest song

or prevent

the Watts Riots in 1965

which left 34 dead.

I mean

it’s called

The Emancipation Proclamation

but what I don’t understand is

when we were proclaimed

or when Black People were

supposed to have been proclaimed free

what did freedom mean?

Station 4: BIGLovely

Toshi Reagon and BIGLovely at last appeared on the bandstand. Toshi Reagon, daughter of civil rights icon Bernice Johnson Reagon, founder of the legendary a cappella sextet Sweet Honey in the Rock, has long surpassed the dynasty label. She is a power in her own right. Sitting center stage with her guitar and wearing jeans and a pork-pie hat, she was flanked by vocalists Carla Duren and Josette Newsam in matching songbird yellow. The rest of the band in outfits of their own choosing included Alex Nolan on guitar, Ganessa James on bass, Kim Ordan on keyboards, and Allison Miller lighting up the drums.

BIGLovely! They describe their ensemble as “a congregational band.” “You should hear everyone you see on stage. Church and a heavy metal concert.”[5] It was all of the above. For a full hour they rocked! Exquisite harmonies, rousing calls for justice and compassion, sassy flaunts of full-body sensuality, and, as individual band members took virtuosic solos, an infectious camaraderie. The line-up of songs was a mix of their popular tracks, “Freedom,” “Beauty,” “Beautiful World,” “Tell Me How Great Is the Land Of My People / Or It’s Not Right” and “Anywhere I Can,” as well as renditions so new they were not available to be published. In keeping with the spirit of this Juneteenth inaugural event, it was a once in a lifetime performance. In between songs, Reagon preached, in a bemused concert banter, the gospel of Afrofuturist liberation.

Carla Duren, Toshi Reagon, Nona Hendryx, Allison Miller, Josette

Newsam and Helga Davis (L to R). Photographer Ifa Bayeza.

Though balmy, the rain became noticeable, still no one left. The entire evening’s ensemble gathered on stage for the finale. Nona Hendryx took the lead. The metamorphosis of Labelle alto into solo singer into revolutionary performance artist complete, this septuagenarian wonder in spandex tights and six-inch platform heels, strutted and defiantly tossed her black creole locks about, challenging and daring all:

Bring me your anger

And linger safe in my arms the sun will still rise

Love's not a prison Love's wisdom will help you rise above

Fear and Pride

Let's give love a try!

At Reagon’s call to the audience, Rux and the colleague beside him—veteran Alvin Ailey dancer Sarita Allen—got up and began to march in step toward the bandstand. Several rows behind, with my black umbrella in tow and my shawl the multi-colors of a seven-day candle, I got up and began to step in unison behind them. Moving to the groove of BIGLovely’s heavy metal, bluesy, Black funk, my feet found their rhythm in that classic syncopated three-step of the New Orleans second line. As we turned the corner in front of the bandstand, Carrie Mae Weems joined in, bringing her friends along. Before long, nearly the whole audience was a parade of black umbrellas marching counterclockwise to the beat, honoring with our footsteps the space between history and future, the sorrow and the promise, the dead and the living.

Station 5

During my slow walk back toward the train, the event continued to season in my mind. In two short hours, I had traveled a great distance: from ancestral waters to our dubious monuments to a Revival and righteous rally cry. Day had turned to night. The streets were filled with raucous crowds, exuberant in their release from COVID quarantine. The air, absent months of Manhattan traffic congestion, was still fresh. I wished more people had been there, but then I thought about those few hundred people, stranded on that other island, Galveston, weeks, months, years after their fellow Africans had been freed from the fate of the perpetual imprisonment that had been our lives. A wave of emotions swept over my body. A light mist kissed my cheeks. I could smell the rain.

[1]Carl Hancock Rux. Blackamoor Angel, composer Deirdre Murray, director Karin Coonrod, dramaturg Morgan Jenness. Joe's Pub, New York City, February 23, 2008. See also "Angelo Soliman," Black Central Europe, accessed September 8, 2021. https://blackcentraleurope.com/sources/1750-1850/angelo-soliman-ca-1750/.

[2]General Gordon Granger, quoted in Clint Smith, How the Word is Passed (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 2021), 173-74.

[3]Carl Hancock Rux, Interview by Ifa Bayeza. New York City, June 29, 2021.

[4]Ifa Bayeza, "The Ballad of Emmett Till." Goodman Theatre, Chicago, IL, 2008.

[5]Toshi Reagon, quoted by Carl Hancock Rux, Rux interview.

IFA BAYEZA is a playwright, author, director and conceptual artist. The Till Trilogy, her epic trio of plays on the life and death of Civil Rights icon Emmett Till will premiere at Mosaic Theatre of DC in the Fall of 2022.

Editor's Note: After this review was posted, we received the following response from the event’s producers: “Neither Carl Rux, Jamel Gaines, nor Lincoln Center had the intention of doing anything related to ASL. The project instead intended to amplify the voices of the oppressed, not to oppress others.” They also note that the review is “beautifully written and wonderfully thoughtful,” and that any discussions “of one small section ” shouldn’t overshadow the whole.