Beethoven's Little Song

- By Ashish Xiangyi Kumar

Taidō Shūfū, Ensō (19th century) (Detail). Hanging scroll; ink on paper, 11 1/16 in x 24 5/16 in. Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Taidō Shūfū, Ensō (19th century) (Detail). Hanging scroll; ink on paper, 11 1/16 in x 24 5/16 in. Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Let’s talk about the last movement of Beethoven’s last piano sonata.

This is a very, very difficult thing to do.

One, because you’re already thinking of this piece as a masterpiece, because who wouldn’t, faced with the connotations of that first sentence? And there is nothing that burdens music like knowledge of its greatness. In fact such an extensive mythos has accreted around the final movement of the Op.111 Sonata—re: its sacredness, its expressive power, its nibbling at the boundaries of what we think of as the sonata, or even art—that it’s sometimes very hard to listen to this piece as music, as opposed to civilisational artefact. By writing this I too risk contributing to precisely this problem—of people treating this work as an object, something to be either regarded from an awesome distance or reduced to its constituent parts, instead of something to be encountered, and lived with.

Two, because you just can’t talk sensibly about this music, sitting right in the heart of the classical tradition, without also talking about jazz (swing! shuffle! boogie-woogie!), minimalism, the musical limitations of the piano, the puzzling rite that is today’s concert experience, and even power, in its ordinary social dimensions.

That is a lot. But there’s also something pleasing to the thought that you have to write about Beethoven the way Beethoven wrote music, with a sense of grand and necessary overreach. So it’s worth a try.

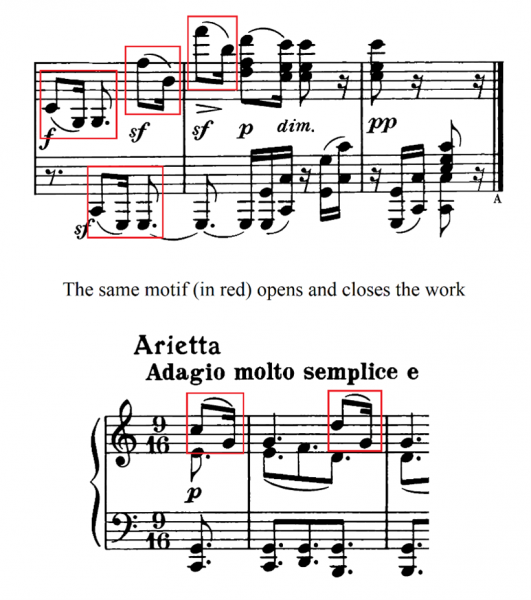

At base, this movement has a simple structure: a theme followed by six variations. Beethoven calls the theme an “Arietta,” a little song—which, frankly, is a terrible name for it. To my ear, there’s really just one way in which the theme is songlike: it’s simple. It comprises one refrain in C major, repeated, and one in A minor, also repeated, and neither contains any real dissonances or harmonic forays. But the music is otherwise not very songlike at all. The melody is slow, rapt, confessional; the notes are presented processionally, with a texture much closer to chorale than song. This is still music: a huge pool of emotion, yes, but nothing on its surface moves.

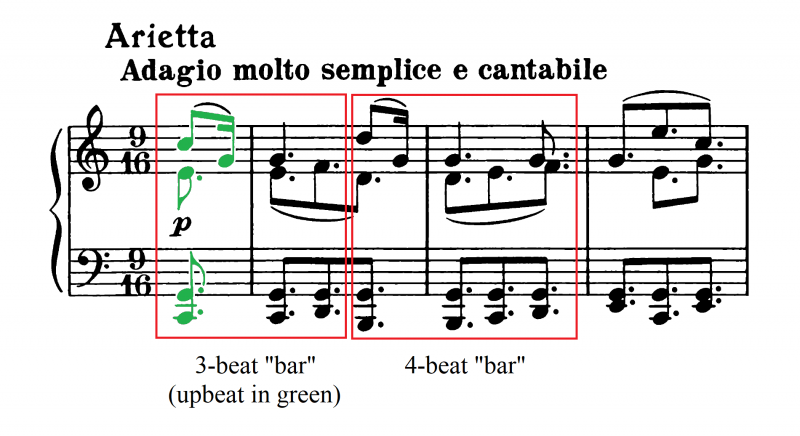

Although there is a fixed quality to this theme, an expressive reticence, it is not frozen: it isn’t the titanic, glacial mass of the Hammerklavier’s third movement, or even the sedate self-obsession of the Appassionata’s. There are small freedoms here. For one, the Arietta begins on an upbeat—a musical intake of breath that prepares for the proper entry of the theme—that is impossible to hear as an upbeat.[1] With the result that, instead of hearing one upbeat followed by two bars with three beats, you hear one bar with three beats, then an off-kilter bar with four beats, before the music returns to the correct three-beat pattern.[2]

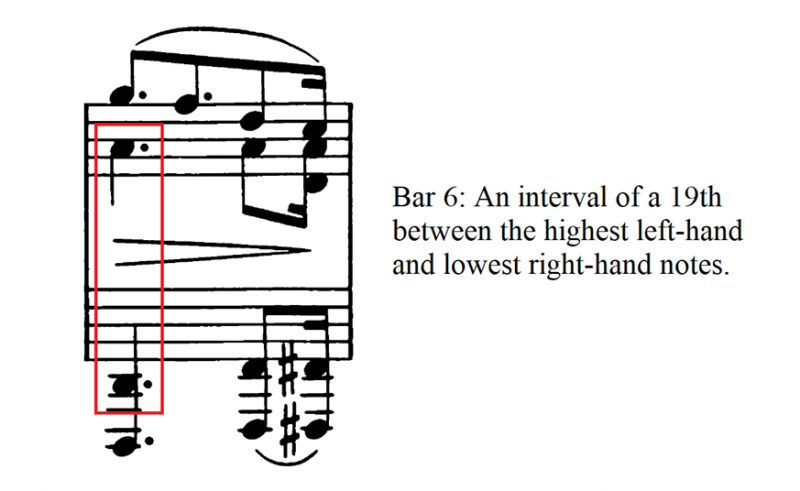

This rejiggering gives the melody, poised as it is, a kind of phrasal freedom; it sounds like speech, like breath. There’s another thing: in the Arietta the hands at times drift very far apart, creating an aural gulf in the piano’s middle. The mind often fills this sense of space with whatever it wants: a sense of loss, for some, for others, a gesture towards the sacred. Take this especially poignant moment in the theme, when a bell-like dissonance in the right hand floats over a fathomless D:

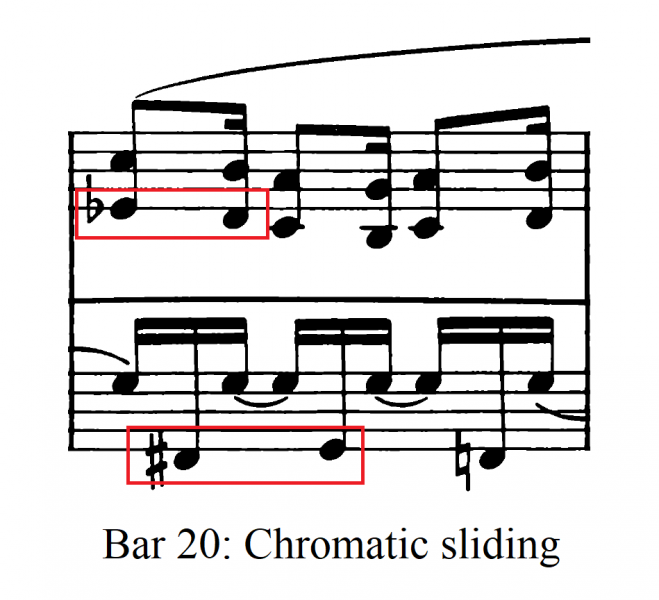

Almost unnoticeably, Variation 1 slips in, performing the simplest of alterations to the theme: borrowing the Arietta’s upbeat, it unfurls each beat in the bar into three notes, and adds chromatic touches to the voices as they shift around. The theme starts to move, and by that I really mean it starts to swing. It’s a real puzzle to me why people tend to describe this variation as lullaby-like, because it’s altogether too coy, especially with its chromatic colour—the effect is more wry, relaxed, discursive.

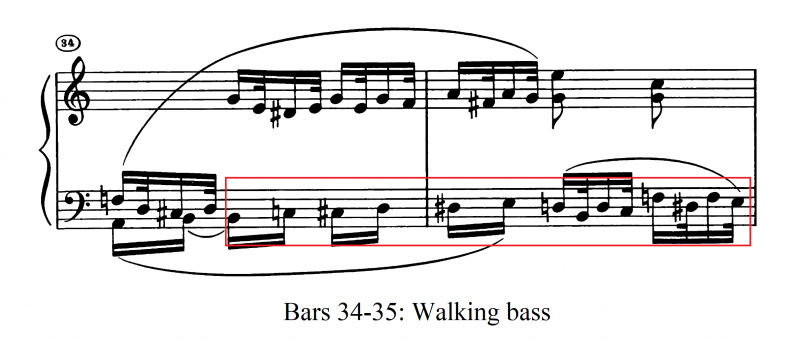

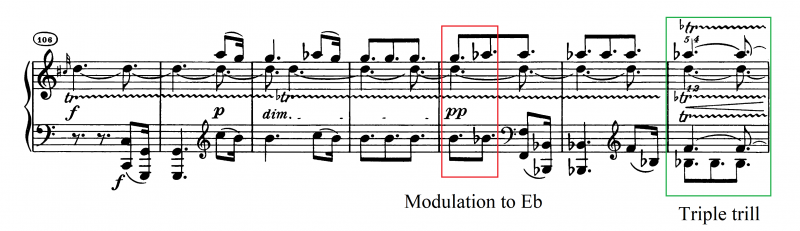

Variation 2 effectively doubles the perceived tempo by stuffing two swingy triplets into each beat, where the previous variation managed just one. The music takes on, slightly improbably, the character of a shuffle. At bar 34 we are treated to a walking bass:

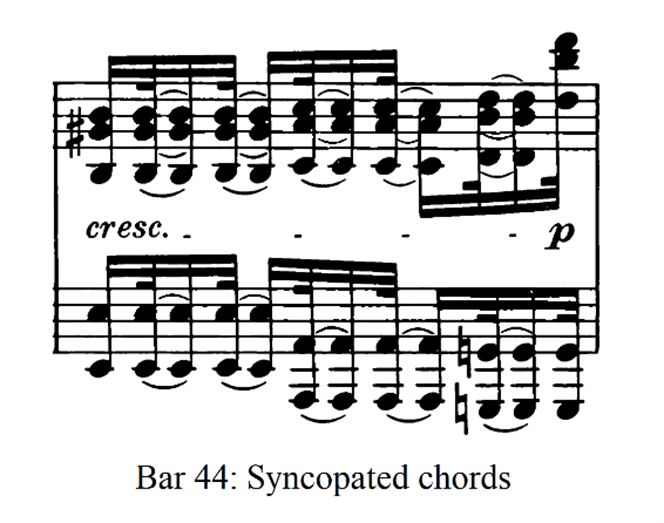

And, at the exact moment the music leaps back into C major from A minor, we’re served a full fat bar of syncopated chords, so that the music suddenly judders like a live nerve:

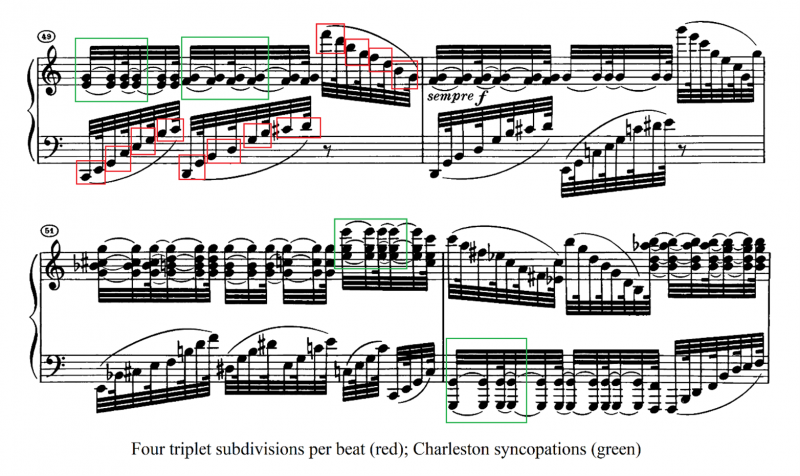

Variation 3 erupts onto the page and in the ear. For those hearing it for the first time it invariably comes as a huge shock, because it sounds overwhelmingly like boogie-woogie. Each beat in the bar now contains four triplet units, driving a swing so intense you feel it in your teeth. Both hands bubble with Charleston rhythms; even the occasional chromatic deviation sounds quite a lot like ragtime decoration. On the page the music looks like terror; in the ear it is a joy so fierce it reaches frenzy.

Let’s talk about jazz.

By which I mean, let’s talk about the fact that no one who discusses this variation seems to want to talk about jazz. Among the more well-known guides to the Beethoven sonatas, Tovey, Rosen, Fischer, and (of course) Schenker don’t mention jazz at all; Stewart Gordon, in his 2016 handbook, does, but in a way that places the observation at a cool distance, scare quotes and all: “The rapid division of three-note units in this variation has generated the frequently encountered observation that this variation sounds ‘jazzy.’”[3] We are meant to understand there is something suspect in the modern listener’s gut reaction to this variation, and that the listener who really appreciates this music should stop hearing jazz in it.

And, in one sense, this is entirely right. This music does not come from the jazz tradition at all: it is, most fundamentally, not improvised music. Neither is it influenced by the confluence in 1860s America of European musical sensibilities and vastly different musical traditions ferried across the Atlantic by the slave trade—as, for example, many of Ravel’s or Stravinsky’s works are. As an analytic fact, it’s easy to show that Variation 3 is far from a miraculous discovery of a new language: it’s just the logical result of a process Beethoven has set up in the previous two variations, viz. more finely dividing each beat into triplet units (in Variation 1, each beat contains one triplet unit; in Variation 2 two, and in Variation 3 four).

The accusation, in short, is that hearing jazz here is anachronistic.[4] But this claim is as meaningless as it is trivial: it suggests that we must listen to this music as Beethoven heard it, whereas we tend to think that the best composers speak across time—and thus that anachronism and displacement make their work stronger, not weaker. More fundamentally, there’s just no way that any of us can extract ourselves from the now, constituted as we are by it, so all artistic consumption post-moment-of-creation is anachronistic. But this is where the fun is. There is something disarmingly wonderful, something so serendipitous as to be anything but, about how as Beethoven reaches for ecstasy he constructs a sound that anticipates and intersects with a radically different musical tradition. Jazzy inflections are not at all new in the classical tradition (the French Baroque had its own tradition of improvised swing[5] and Bach uses some very jazzy syncopations in the second fugue in The Art of Fugue[6]), but here they are pushed with typically Beethovenian single-mindedness to new extremes. If you’re like me, and your ear can be dulled by familiarity, listening to Variation 3 can be a brute aural reminder of how radical and powerful even the earliest blues forms were, how they said things that other musical languages could not capture. And in the context of this movement, Variation 3’s power is heightened immensely through contrast with the surrounding material: in some recordings (Michael Korstick’s) this variation is like a magnesium fire, so metallically white-hot it is nearly unbearable, and in others (Mitsuko Uchida’s) it is a jubilant trance.

There’s one other thing worth pointing out: Variation 3, despite the swarms of densely feathered notes flooding the page, is slow music. All the variations in this movement take as their subject not the Arietta’s melody, but its harmony: and the underlying harmonic changes have not changed in speed at all (Beethoven even marks Variations 2 and 3 L’istesso tempo—the same speed—to underscore this point). It takes a bit of effort, but if you abstract your ear from each individual note, you can hear the long arc of the chorale humming away tectonically underneath it. A disorienting and mentally taxing experience, but worth the effort: when you do manage it, the feeling is both deeply pleasurable but also weirdly disembodied, as if your soul is leaving your body.

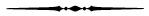

Variation 4 is two variations rolled into one. In the previous variations, both strains of the theme (the C major and A minor) are repeated exactly, giving each variation AABB form, but here each repeat is radically different, creating an A1A2B1B2 structure.

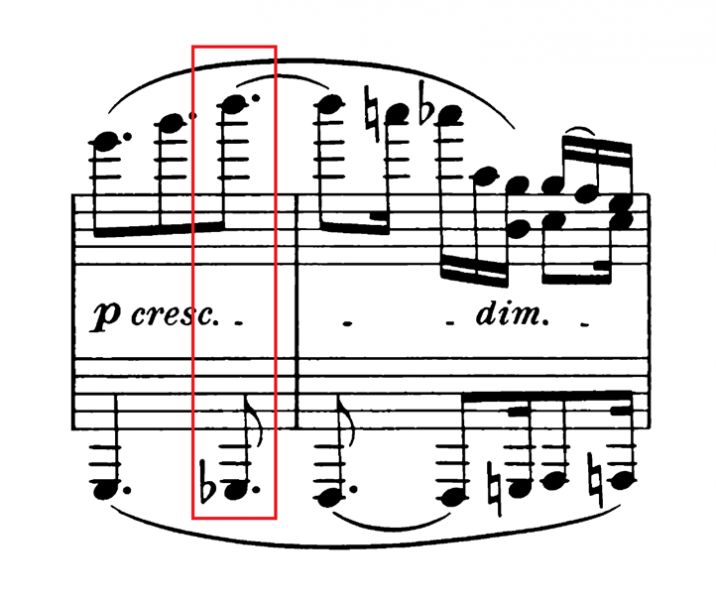

In the first subvariation, the theme is deconstructed: it collapses into a set of indistinct pianissimo chords, each of which enters lagging behind the beat. Low in the piano, these chords sound over a C/G drone[7] which rubs up almost imperceptibly against the changing harmonies above. This is the first time we hear the theme in a genuinely reduced form, and the first time the movement sinks into darkness. As a result this subvariation is both frozen and transitional; dull, yet drawn tight with unbearable tension.

The second subvariation is an exercise in minimalism. The music climbs into the high registers; the left hand picks out wafer-thin chords, while the right unspools a crystalline chain of scales that obsessively circles around itself, seeming to repeat but never quite doing so. This unusual feature of the music—the way it changes while not seeming to change at all, the trick through which perpetual movement is used to generate stillness—makes it of a kind with the work of the great minimalists who would come much later: Glass, Reich, Riley.[8] It’s infuriatingly hard to describe how vulnerable[9] this music sounds, how tiny and breakable, especially when you reach the devastating A minor strain.

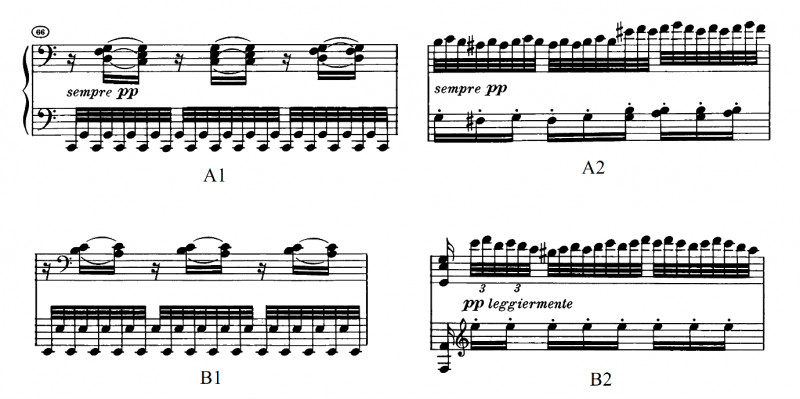

Something strange, even violent, happens here. Up to this point, every single bar of music has been derived strictly from the main theme. But at bar 96, almost unnoticeably, the music comes untethered from the underlying harmonic scheme:

Ask any pianist familiar with this work about this passage, and their eyes will glaze over a bit, because this passage, without fail, makes your hair stand on end. Why? The numinous halo of the high register, the tiny dissonance of the pulsing chords below? Well, yes, but there’s also something happening at an even deeper level, almost beyond the point of sensory experience: you hear the departure from the structure, the leave-taking that Adorno wrote about.[10]

Then the music drops an octave, and from what seems an impossible pitch of loveliness, it broadens into new deltas of feeling.

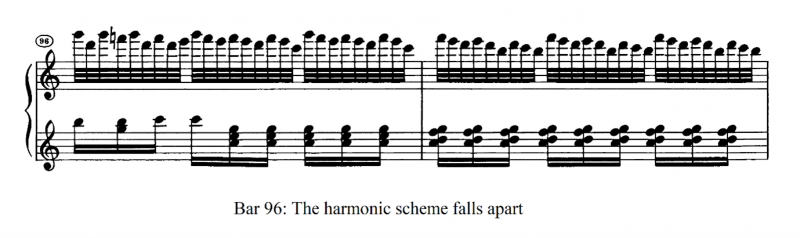

It’s worth taking a moment to realise how absurdly rare it is for a work to be this generous: to reach one expressive height, and then immediately top it, and then top it again. Music in the classical tradition, with its well-defined transitions and build-ups and climaxes, generally doesn’t admit this kind of indulgence. And yet here we have all of this happening, without any fundamental tension in the music. That passage above? It’s a stereotypically pop-ish I-vi-V progression, the kind that is quite happy to loop on forever in a chorus, but it’s made extraordinary by context and craft; it even introduces a new melody in the left hand that incorporates touching dissonances in its peaks.

Ordinarily, this rupture in the structure would signal that we are now in the coda, the concluding section of the work. And, true enough, the passage does finally comes to rest, rather self-consciously, on a supertonic trill.[11] This is typically a way of saying pretty decisively that the ending is here.

Except, of course, the ending doesn’t come.

Let’s talk about trills.

By which I mean, let’s talk about the piano.

The piano is a forgiving instrument: if a person who’s never touched a piano before strikes a key, they’ll produce just as beautiful a sound as Argerich or Cherkassky.[12] But the simple physical mechanism—hammers striking strings—which so neatly levels the aural playing field also brutally cripples the piano: once it makes a sound, that sound can only die away.

Beethoven hated this. I mean, really hated this. Perhaps the most obvious evidence for this is in some of his piano sonatas, where he writes dynamic indications that are impossible on the instrument.[13] But the trills—and his work is replete with them, whether violent (the Hammerklavier’s last movement) or lyrical (the Fourth Piano Concerto)—are another sign of his frustration at the instrument’s limitations. At root, trills are a way to make a piano do what it can’t: sustain a sound. But there’s something wicked about trills too, something multivocal and restless. By oscillating between two notes, they become dissonance, at once prolongation and interruption, a pinpoint mass of sound forced to shudder in one spot like a particle trapped in a field.

So that trill on the D? It doesn’t resolve. It’s a trill designed not so much to go somewhere as to suspend any musical movement, like a word repeated so often it loses meaning. And right when we’re on the brink of having the whole thing dissolve into noise, other notes creep in around the trill, giving harmonic context—and then, for the only time in the whole work, we modulate(!) into Eb major.

The trill, already by now one of the longest in the repertoire, implacably thickens into a shimmering triple trill.[14]

Now that we’re in Eb major, you’d really expect Beethoven to do something in this key. Instead the trill mounts upward (and we’ve been listening to a whole solid minute of trills now), until it dies away into single notes in the desolate Himalayan ranges of the piano. Out of nowhere the left hand growls out a note deep in the bass; this new line begins a descent as the right hand continues to climb.

At bar 118, a vast gulf opens up between both hands:

A lot has been written about this moment. Most commentators reach for religious metaphors: Schiff thinks the gap is the separation between heaven and earth; Seymour Bernstein thinks it enacts crucifixion (of all things!). Truthfully, what is extraordinary about this moment is how the huge chasm seems to express literally nothing at all. The notes are so far apart their frequencies do not interact in any sensible harmonic way; at those extreme ranges, all that comes through is the raw fact of the piano’s sound, bright and rigid at one end, a dark mineral clot in the other. The fact that the upper notes in bar 118 actually trace out a fragment of the Arietta melody doesn’t register. If I were forced to metaphorise this moment (and it really is too wonderful to be metaphorised), I’d say it sounds like possibility: this is one end of the piano, this is the other, and you are free to put anything you want between them. But the most honest thing to say about this moment is that it is a mystery. Something, as Wittgenstein might have said, to be deepened rather than explained.

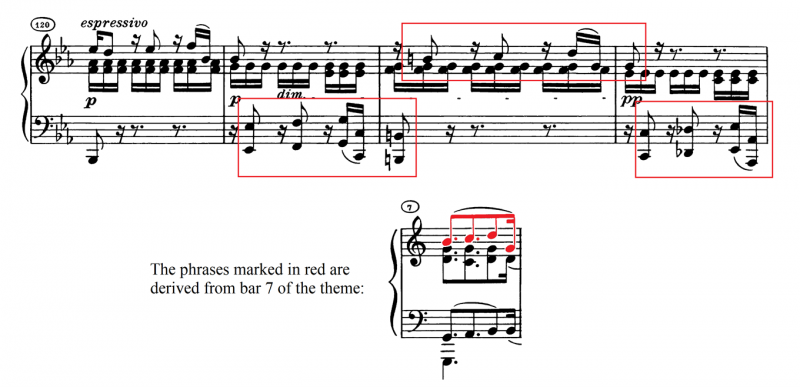

When the moment passes, we are left in a tonal crisis: we are in the wrong key, Eb major, and Beethoven must find his way back to C. And so there begins the most Delphic passage in the work, a long and agonising modulation, replete with bewildering syncopations (the melody notes land, with wilful perversity, in the middle of each beat) and keys drifting in and out of focus. Amazingly, this whole move to Eb has nothing, really, to do with the theme and its variations; it has no home in the formal requirements or typical structures of the form. Commentators struggle to label this passage: Gordon calls it an “interlude,” while Tovey calls it a “modulating coda,” which forces him to awkwardly conclude that a “da capo of the theme” and an “epilogue” are still to come. The motivation for this passage is entirely expressive and anti-formal. This explains why the closed universe in Eb never presents a restatement of the theme, or any real development of it.[15] This passage is not there to say anything about the rest of the work. It’s there to disrupt it, to put a fault in the architecture.

Variation 5 arrives with a sense of homecoming so powerful that it becomes a physical sensation: the bass notes start chromatically tightening around a G, a C major arpeggio swells out of the bass, and order returns.

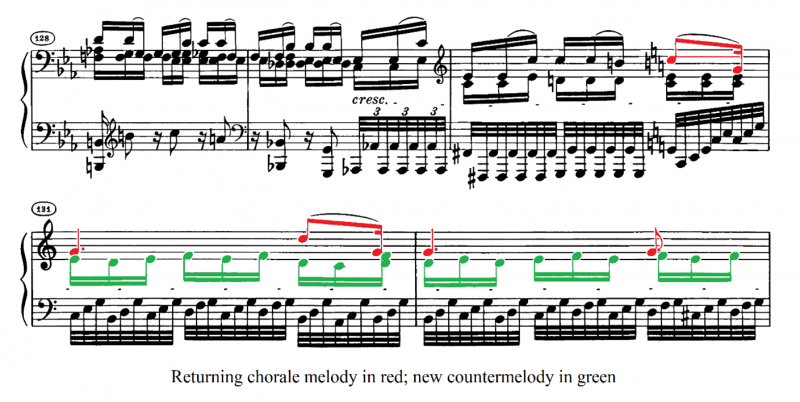

Almost universally this particular variation is described as expressing compassion or gratitude, which is both entirely correct and utterly senseless. Because compassion or gratitude aren’t really feelings, are they? They’re normative attitudes, other-regarding things, stances, positions that seem much too complex for instrumental music to express. And yet this music gets there. The why of this may never be fully parsible, but there are at least some sensible things we can say. There’s probably something in the fact that this music is returning after extended wandering in harmonic wilderness. But more strikingly, for the first time in the whole work the actual melody of the Arietta returns, although profoundly transformed. It’s no longer austere: the distance between both hands has been closed, the melody is hugged from beneath by a beautiful contrapuntal line, and the bass is a distant, benign rumble.[16]

The bliss of Variation 5 sustains itself for 29 bars—an absurdly long period to sustain this kind of emotional intensity, amplified by the fact that Beethoven actually introduces an extension to the theme for the first time—before we arrive at the last variation.

Let’s talk about variation form.

More specifically, let’s talk about a huge, even devastating problem which inflicts it, viz. its lack of any natural sense of order or finality. Most musical forms—binary, tertian, sonata, rondo—set out procedures which force an ending, so that every musical idea enters carrying the implied fact of its termination. But variation form has no natural end. Once a theme is introduced, you can, in principle, keep on varying forever, since no structural impulse checks the momentum you’ve built up. And so the history of the great works in this form is essentially a catalogue of ingenious solutions to this problem. A common one is to end a set of variations with a fugue, since a fugue’s relentless self-referentiality represents (you could convince yourself) the most internally rigorous way of examining a theme—you put a fugue at the end to say, basically, “Ok, now there’s really nothing left to be said.” Beethoven himself does this in the Diabelli Variations, as does Brahms in the Handel Variations. Another (terrifying, ingenious) solution is to superimpose a multi-movement sonata form over a variation structure. Rachmaninoff, who never shied away from dense, internally intricate structures, was particularly good at this. Yet another solution is to set up a cyclic structure and then interrupt it, as Bach does in his Goldberg Variations.[17]

The ending of the Op.111 does none of these things; it works its way into a far stranger conclusion. Essentially, Beethoven writes a work which has no end.

This needs a bit of explaining.

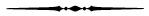

Thus far, each variation has used successively smaller note values. Variation 6 arrives at the terminal point of this process: the right hand takes up a trill on a high G, its individual notes now so finely divided that they have no particular rhythmic value at all.[18] Under this trill the right hand just about etches out the chorale tune, while the left hand vibrates in thirty-second notes which gently abrade the trill above.

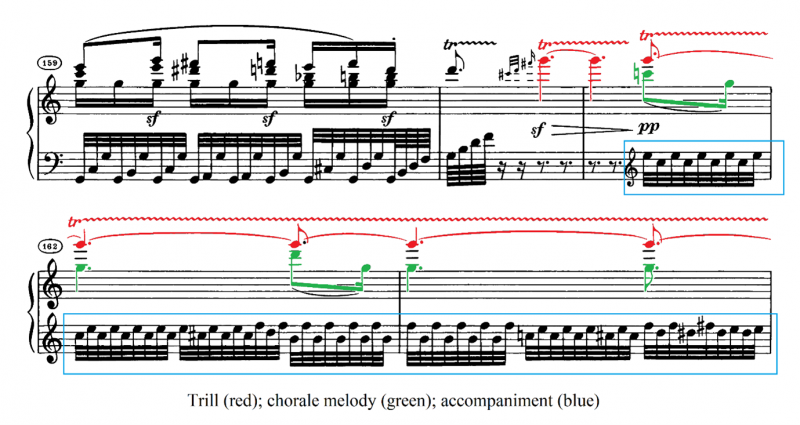

So far, so logical. But here’s the rub: Beethoven never completes this variation. We should expect, by now, to hear each strain of the theme twice in Variation 6—AABB form. But we get only A, the first strain, before the theme just cuts itself off with a new five-note figure.[19]

Immediately after this strain, a delicate set of scales, recalling Variation 4, takes us up and down the keyboard. And then, in the last three bars, the opening upbeat motif of the theme enters in quick succession across wildly different registers, bringing the work, abruptly, to a close.

I want to stress how aggressively weird this ending is: there is no real melody, or sense of the three-beat bar. The motif makes leaps so large its notes don’t properly connect to each other. The final chord is muted, throwaway, terse. If so minded, you could argue pretty persuasively that this ending, with its awkward phrasing and gangly harmony, is pathetically inadequate to what has come before—all that generosity, that heavenly length.

Yet all this happens because Beethoven, in this movement, treats variation form as a process of liberation. Every variation loosens the leash slightly, gives the theme a bit more freedom, until not only do we escape the idea of rhythm (the trill), the theme itself becomes liberated from its own structure. The work opens up, opens up, opens up, and then it is nothing.[20] In a sense, it trails off into infinity. The ending Beethoven writes, the one which registers as actual sense data, is a conceptual ellipsis: it gestures back to the opening and opens up, for the last time, that gap between the hands that signals the possibility of creation, as if the real music was still sounding.

Let’s talk about Covid-19.

I kid. Let’s talk about the modern concert experience.

It’s hard to imagine music less suited for the concert hall than Op.111’s concluding movement. For a start, it’s far, far too intimate, and even then not so much intimate (which implies contact or communication) as innermost. There is no point at which the work turns gestural,[21] in the epic manner at which Beethoven was wildly gifted (think: his symphonies, piano concertos, a good third of the sonatas). Its length, its spaces, its griefs, and joys, are all private. The idea of listening to the Op.111 resounding from a stage dozens of metres away while you’re seated among strangers, strikes me as a terrible transgression of this music. But more fundamentally, this piece just does not cohere with the idea of concert performance. The concert hall is basically a dictatorial space: we are at the command of the performer, and we are instructed into awful passivity. The music lays an ironhanded claim on our time; we cannot ignore it as we might a painting in a gallery. The usual procedures by which we try to construct community/ intimacy/understanding are (in traditional concerts, at least) forbidden. You cannot speak to those around you; you cannot ask the pianist to repeat a particular passage you either loved or didn’t really understand; nor can you ask the pianist why a passage was played a certain way. Even the most basic way in which we respond to music—with movement—is forbidden (although, perversely, this rule is applied only to the audience; the conductor is free to dance).[22]

Which isn’t to say that nothing rescues the traditional concert. Musicians take many more risks in live performance than they do on record; there’s a shared and indisputable vulnerability to concert-music. Nothing you hear at home will replicate the earth-shaking force of an orchestral climax experienced live. And, to be honest, lots of music really works, when presented in the imperious take-it-or-leave-it form that the concert hall demands. But for this Arietta, the concert hall does not suffice. This music is altogether insufficiently authoritarian. Its posture is one of vulnerability and confession; it asks for the option of being turned off at any time. Freedom is such a basic part of its meaning/organization/texture that it is deadened by live performance, reified.

How to listen to this, then?

Answer: there isn’t a how. The music will justify itself to you, or it won’t. As basic and obvious as this point is, it bears repeating that nothing in what I’ve written above is not in the music. If it’s not there in the conscious mind it’s certainly there in feeling. This music makes no special claim to our time or attention; it’s too good for that.

The Arietta starts sweet and still, a little desolate, and grows intimate; it starts constrained and grows free. Our little song is something to keep close these days, where we’re each lodged in lonely, intimate spaces, wondering about small freedoms.

ASHISH XIANGYI KUMAR is a junior diplomat in the Singaporean Foreign Service. He writes on music and runs an eponymous YouTube channel.

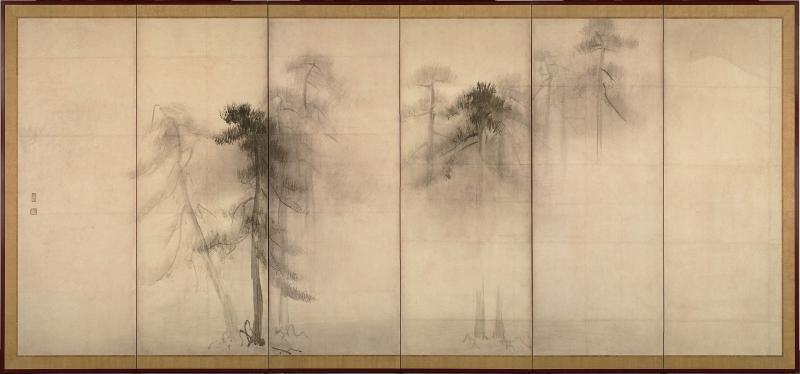

Hasegawa Tōhaku, Pine Trees (Sixteenth century). Pair of six-folded screens; ink on paper. 5.2 ft x 11.6 ft. Tokyo National Museum.

[1] Rhythm, and how we perceive it, is a ferociously difficult topic to write about. Thankfully, there’s a relatively simple reason why this particular upbeat is so hard to detect. An upbeat usually has a prefatory or unstable feeling—it cues in the music, after all (think: the “Happy” in Happy Birthday, or the “Oh” in The Star-Spangled Banner). The problem is that the upbeat Beethoven writes here is occupied by the most stable, complete-sounding chord you can write in this key: a C chord, in root position (i.e., with the C sitting contented at the bottom, not wanting to go anywhere), spaciously and beautifully voiced. Critically, this upbeat chord sounds just as rich and full as the music which follows, so that nothing distinguishes it from the melody proper. To get a sense of how an upbeat should work, listen to the opening note(s) of Chopin’s first six nocturnes. Chopin’s left-hand harmonies only enter on the downbeat, separating off the opening upbeats. There are no such rhythmic signposts in the Arietta. (I suppose we shouldn’t be too surprised, because the Arietta isn’t the first time Beethoven disguises an upbeat in his sonatas. An even more perverse upbeat opens the Sonata No.10, placed not so that you don’t hear it, but that you hear a longer upbeat than you’re supposed to. The result is that your sense of the bar lags behind the written music by an eighth.)

[2] There are some pianists who insist that the opening be played so you can actually hear the upbeat. This seems to be an instruction to expend a lot of effort to make a work sound less interesting, which baffles me.

[3] Stewart Gordon, Beethoven’s 32 Piano Sonatas: A Handbook for Performers (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 264.

[4] This might be charitable, because it’s sometimes hard to avoid the impression that (at least among some European commentators) the comparison to jazz is resisted because it’s seen as degrading to Beethoven’s work. András Schiff (never anything less than a superb interpreter of Beethoven) is unusually blunt about this; in his recital-lecture on this sonata, he insists that “…there is nothing jazzy about [Variation 3],” before cautioning his audience that “[t]his is the most spiritual creation of the most spiritual composer, so let’s not associate it with banalities.” I guess it shouldn’t be so surprising that white supremacy still scaffolds notions of the “correct” understanding of this work, given that it was on the continent that Beethoven first became co-opted—even by luminaries like Adorno (implicitly) and Schenker (explicitly)—into a project to demonstrate the superiority of (certain kinds of) European culture. It’s also worth noting that commentators tend to happily embrace anachronism elsewhere: there are no scare quotes when Bach is compared to Schoenberg, Beethoven to Shostakovich, or Gesualdo to Poulenc, though here we could make the excuse that at least these composers belong (however tenuously) to a common musical tradition.

[5] Called notes inégales (“unequal notes”). A nice example of how this sounds is this fantastic performance of Rameau’s “Les Sauvages.” The orchestra, when it enters about forty seconds in, plays what are written as ordinary eighth notes with a distinct swing feeling. At times the ensemble even comes very close to using the quintuplet swing much beloved of the YouTube jazz commentariat these days.

[6] See for instance Glenn Gould’s pleasingly motoric performance.

[7] People often describe the left-hand figuration here as if it’s a tremolo—a free oscillation between two notes—but it’s much more cunningly organised. The thirty-second notes in the left hand, as they alternate between C and G, are grouped into threes, with each group of three beginning alternately on a C/G. Three of these groups form each beat in the bar, and each of these beats also begins alternately on a C/G. And each bar, which contains three beats, also begins alternately on a C/G. Basically: the C/G oscillation has a fractal structure, self-similarity at different rhythmic scales. As a mathematical fact, this amounts to no more than the observation that no power of three is divisible by two, but as a textural feature, this gives the bass oscillation a kind of uncertainty and freedom you’d not find in an ordinary tremolo.

[8] Perhaps a strange comparison, yet the steadiness of the left hand always reminds me of the hypnotic C pulse of Riley’s In C: there is something almighty about it, even in its tenderness.

[9] The one recording I know of that fully captures this unbearable fragility is Ivo Pogorelich’s; like Cortot, he seems able to find everything in a piece of music that is otherworldly and intoxicating.

[10] Theodor W. Adorno, Beethoven: The Philosophy of Music, ed. Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Cambridge: Polity, 1998), 175.

[11] This is nothing more than a trill on the note just above the tonic (“home”) note—a D in this case. To get a sense of how powerfully a supertonic trill can close a phrase, listen to how it concludes this phrase from the Kyrie Eleison of Mozart’s Great Mass in C Minor, or this one from the K.545.

[12] This is one of those surprising but mundane facts that a lot of writing about piano-playing tends (deliberately or otherwise) to obscure: the only possible factor that can affect the tone of a single note on a single piano is the speed with which the hammer hits the string. There’s no other variable available to the pianist to change: the weight of the hammer, its contact point with the strings, and the manner of the contact is fixed (setting aside the una corda pedal). In fact, it turns out that just before a hammer hits the strings, a mechanism called the let-off separates the key from the hammer, which means that at the exact moment a piano produces a sound there is no physical connection between the pianist and the mechanism producing sound. A pianist’s job consists therefore of—literally—throwing hammers at strings.

The implications of this are profound and depressing: for one, it means that there is no way to separate volume and tone on the piano; if you want a harsher tone, you’ve just got to hit the keys harder, and also produce a louder sound. It also means that no matter how caressingly or violently a piano’s keys are hit, the sound produced will be exactly the same so long as the keys are depressed at the same speed. Compare this to the violin, where you’ve got direct physical control over so many factors in sound production: which part of the bow you use, which part of the string it contacts (sul ponticello, sul tasto), the manner of the bow/string contact (sautillé, spiccato, martelé, ricochet), the speed of the bow/string contact, the weight of the bow, whether you use the bow at all, even the precise manner in which the string vibrates (as when you play a harmonic). All this isn’t to say that it’s meaningless to speak of tone on the piano. Different pianos have very different sounds, and some pianists (Krystian Zimerman is one famous example) even change the entire action of their piano mid-performance to get the tone quality they feel is appropriate for a particular piece. And on a single piano, there are miraculous illusions you can conjure once you start moving beyond single notes: the perception of tone can be hugely affected by voicing, phrasing, articulation, and dynamic variation (a chord with the top voice nudged slightly to the fore always sounds sweeter, for instance). But touch a single key on a piano for the first time, and it will give you the same sound it gives a virtuoso. The piano is impoverished; it is also generous.

[13] The Pathétique sonata opens with a chord that Beethoven instructs us to strike at forte, before immediately dropping several tiers of volume to piano, much faster than the sound can naturally die away. (Achieving this trick isn’t strictly impossible on the modern piano, if you resort to depressing the keys silently and using some sensitive pedalling, but it was impossible in Beethoven’s time.) In bar 252 of Les Adieux’s first movement, Beethoven does actually ask for something flatly impossible: a crescendo over a single octave C high in the piano. The same instruction also occurs in bar 39 of the Sonata No.4's second movement and bar 62 of the Sonata No.9’s second movement. These kinds of markings are really not meant for the audience, but for the pianist, as an internal guide to how they should feel the music. But they have no relevance in sound.

[14] Triple trills are rare in piano literature, but this is not the first time Beethoven uses one in a sonata. In the last movement of his Sonata No.3, he writes an absurd little supertonic trill that builds into a triple trill, refuses to resolve, and then slips (embarrassingly) into the wrong key altogether. In a similar way the supertonic trill here also leads into a modulation, although it is not at all funny.

[15] Actually, fragments of this passage borrow the melodic contour of bar 7 of the theme, but the context is so different that this thematic link is nearly unrecognisable:

[16] This last point is worth emphasising, because there are points when the bass actually turns strikingly dissonant, almost a Bartokian drone—but in the context of this variation it is warm and earthen, a sort of aural petrichor.

[17] The ending is heralded by the Quodlibet, which forcefully enters where there should instead be a canon at the tenth, which in turn clues you in to the fact that something special is going to happen (the return of the Aria).

[18] This procedure is not new to Beethoven. In the magical last movement of the Sonata No.30, the Op.109, Beethoven writes a set of variations on a tender sarabande/chorale (marked “with deepest feeling”). In the last variation Beethoven goes through the entire procedure of intensifying feeling by subdividing a recurring B until it dissolves into a trill. But this is all done in a single variation, while the Op.111 spreads this over twenty minutes of music.

[19] Again, not strictly new, because this too comes from bar 7 of the theme. But in context it sounds new.

[20] There is an alternative reading of the structure of this movement which says that the last two variations really constitute its coda. Some pretty powerful technical critiques could be lobbed at this notion (for a start, a coda is supposed to wrap things up, and this one very definitively does not do that; plus, since when did the entrance of a coda come accompanied by such a powerful and expansive sensation of homecoming?), but the real reason I think this interpretation is wrong is not that it’s wrong but that it’s boring.

[21] I have to emphasize that this comment does not apply at all to the first movement of the Op.111, which is a craggy, fiercely contrapuntal, ultra-gestural thing.

[22] You can add to this the fact that our experience of the music itself is divided. Someone who pays just enough to secure a front-corner seat hears a very different concert from someone seated in the dress circle, so that the traditional concert experience ends up enacting odious materialist hierarchies. In fairness, though, such class divisions—as well as fact that most (live) classical music audiences are old and white—are contingent on how governments and societies choose to fund and consume art, so hope springs eternal.

A PDF of this essay is available here.