Birdsong

- By Keith Taylor

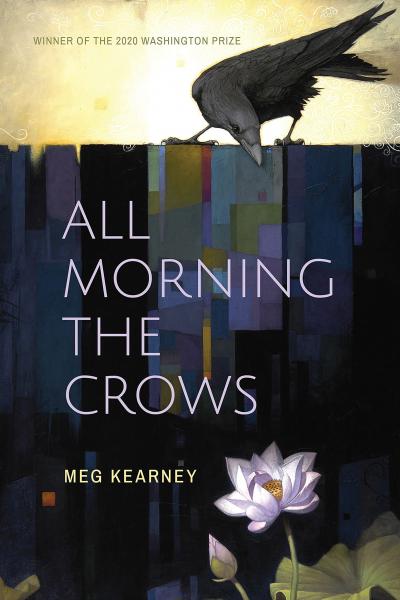

Meg Kearney’s All Morning the Crows (The Word Works, 2021).

Shelley begins his famous, “To a Skylark”: “Hail to thee, blithe Spirit! Bird thou never wert. . .” Then for the next few stanzas he works hard to show the “birdiness” of the bird, until he finally gives up in a series of similes (“Like a Poet hidden/In the light of thought . . .”; “Like a high-born maiden/In a palace tower. . .” etc.). By the end of the poem Shelley wants to learn to sing with the bird’s “harmonious madness” so the “world should listen” to him as attentively as he listens to the bird. He’s yet another poet desperate for an audience.

Even though “To a Skylark” has been easy to parody over the last couple of hundred years, I think it’s a wonderful poem and a marker that shows how poets have gone looking to the avian world for context and inspiration. Shelley wasn’t the first poet to do this, and, if anything, there have been many more poets since. After all, birds can fly! Most of them even build temporary and fragile homes and then seem to disappear! And, of course, they sing! They embody an ever present contrast to our industrialized world. We might be denying something essential in ourselves by not noticing the birds around us. If anything can be said for the pandemic lockdown, it might be that more and more people have been watching and studying birds. On my social media I’ve even seen bird posts and photos by hard-nosed, difficult poets who have laughed at bird poems in the past. Before our isolation, the recent attention paid to ecopoetry has often centered on birds and the threats we present to them (the poet Alison Swan has said that “maybe ecopoetry is just the cool kids’ way of saying nature poetry.”). And no one has been more attentive to the birds of her imagination than Meg Kearney.

Kearney was an adopted child, and the double emotional weight and history of two families have filled her poems. She writes of the dissolution of marriage and the re-emergence of love. She lived for a long time in New York City, even witnessing the attack of 9/11, before leaving the City permanently for a life in the forest of upper New England. That contrast is important to her work. There is a subtle formal accomplishment in her poems that is often disguised by the complexities of her syntax and the directness of her language. For instance, in the poem “Penguins,” I had to be a ways into the poem before the repeated lines registered for me, and I realized I was reading a pantoum:

They looked like little children

standing upright on the shore

the sailors said, still at sea.

All were hungry under that frozen sun.

Standing upright on the shore,

a cluster of fathers and their chicks—

all were hungry under that frozen sun

waiting for the mother penguins’ return.

Just as I was typing that out and wondering why it took me so long to recognize the form here, I realized that the irregular rhymes, even rhymes within lines (“The stunning tails of killer whales. . .”) distracted me, in the best possible way.

Regarding Kearney’s formal abilities, it is certainly worth mentioning that two years ago she published a chapbook, The Ice Storm (Green Linden Press, 2020), a royal crown of sonnets that is extraordinary. It centers around the dissolution of her marriage in the City during the days following the attack on the Towers. I was so absorbed in the material of the sequence that it wasn’t until a later turn that I could see how closely Kearney stuck to the rigid rules of a classical crown, even down to the fifteenth poem, a cento that is made up of the first lines of the previous 14 poems. She might give herself a few small liberties in meter or rhyme, but not many. It is a wonderfully elaborate puzzle, yet the sequence is so much more than that.

But the images that have dominated her poems, that unify them, are avian. In the preface to All Morning the Crows, Kearney tells us that she is “technically not a ‘birder.’” She goes on to make the point absolutely clear, “I am a bird lover who has written a book of poems inspired by—though technically not about—birds.” Yet we see the gorgeous cover of an ominous (or loving?) crow sitting on a fence staring down intently at a flower illuminated by a stray shaft of morning light. We see the title emblazoned on the crow’s fence—All Morning the Crows. And we go to the table of contents to find that every poem is named after a bird, most of them quite common.

The birds in some of these poems are clearly symbols of ideas or emotions that preoccupy the poet. I prefer to call them “symbols,” because they feel weightier, more deeply attached than “metaphors,” although the poet might prefer that more easily defined label. “Scarlet Tanager,” for instance, retells the famous story of Dvorak structuring his “American Quartet in F major” after the harsh call of this brilliantly colored bird:

from an oak’s green canopy

came the high, interrupting strain of a violin

on fire. Next came the second violin, a viola,

a cello, a gapped pentatonic composed by nature,

a scarlet-plumed opus, folk-like but stranger;

next came an American Quartet in F major.

Kearney may not be a birder, but she has listened closely to the bird, as well as the string quartet. Like Dvorak, she is connected to her place through the song of the bird. The bird is symbol of the place, perhaps even the continent.

The most effective poems in this wonderful collection are those that work best when Kearney associates the inner life of the poet with the presence or habits of the bird in her title. These associative jumps might be understood as metaphors, but there is something deeply visceral about them. “Loon” begins

I bought a cassette tape of loon calls so I could speak

their language that summer I camped on Russet Pond.

This was the eighties so cassette tapes were the thing—

side A was for where-are-you-I am here or I-am-hungry

calls, meaning hoots, wails, and peeps; side B was for

aggression and distress—yodels and tremolos, the latter

a kind of alarm laugh that led to the saying “crazy

as a loon.”

She moves easily through bird-lore, popular culture and personal history. The tone seems almost jokey, until we remember that the poet has come alone to camp by a pond. This could be either a search for some kind of nature-transcendence, or an escape from personal trauma. Or both. The end of the poem makes the choice clear—". . .I found I preferred wails to tremolos, wails being the kind of call I’d perfected myself by then.”

This kind of metaphoric juxtaposition is particularly powerful in an elegiac poem like “Pheasant.” She tells us “This pheasant won’t be shot/by fat men after breakfast./This pheasant’s etched in stone,” part of the decoration on her father’s tomb. She tells us: “All morning the crows/have behaved badly,” a kind of distraction around the grave, as well as a delicate and interpretive placement of the title of the whole collection. The poem ends,

Who will save you now?

mock the crows, pulling plastic

tulips from the ground. Not

the pheasant, bound by stone

into silence. Not his brother crow,

that clown, who has staked a claim

to the fresh earth mound where

my mother lies, so newly arrived

she’s still saying her hellos.

There is a surprise here at the end, but it doesn’t feel contrived. The poet has connected her grief to the birds in that place, giving an unforgettable presence to both the birds and the poet’s quiet lament.

KEITH TAYLOR's most recent chapbook is Let Them Be Left: Isle Royale Poems. His last full length collection, The Bird-while was published by Wayne State University Press. He has published many book reviews over the last 40 years, here and in Europe, in newspapers, magazines, and literary journals. After a series of mostly menial but formative jobs, he worked for most of 20 years as a bookseller, before teaching for a few years in the writing programs at the University of Michigan.