In Memoriam, Gianni Celati (1937-2022)

- By Patrick Barron

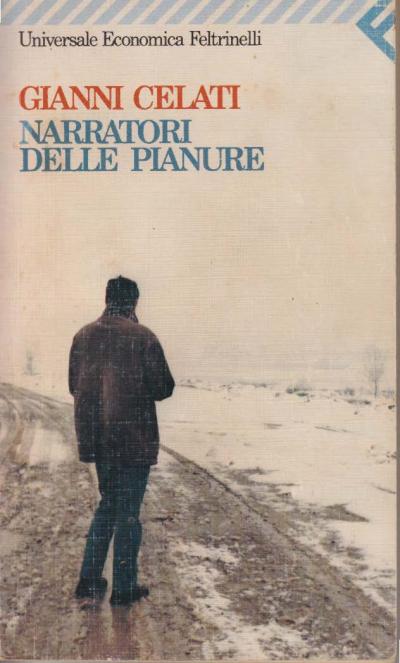

I came to know Gianni Celati through his writings (if knowing a person in this way is possible), beginning in the late 1990s when I found his book Narratori delle pianure (“Storytellers of the Plains,” translated as Voices from the Plains) in a shop in Ferrara, a town in northern Emilia Romagna not far from the Po River, where I was living at the time and working as an English teacher. On the cover is a photograph of Celati by Luigi Ghirri, a lone figure facing away from the camera and standing on a muddy road that curves to the left across a vague expanse of snowy land, slightly crooked and bent over something immediately at hand. I imagine that Celati is taking notes, trying to describe his surroundings—the seemingly nondescript expanse of wintry plain that envelops him—as Ghirri describes him and his location, a photographic frame around the frame of words Celati is writing. None of this was apparent to me at the time, but I found Ghirri’s image haunting, strangely inviting yet also difficult to interpret, and the title of book promised insights into the very same plains in which I was living and attempting to know (yet finding somewhat inscrutable).

As I read this book and others by Celati, then began to translate his work, I was repeatedly impressed by his deep affection for and passionate interest in literature, film, photography, the visual arts, theater, everyday stories, other people, other places, a seemingly endless series of adventures of the mind and body, always tapped into a great sensitivity for an encompassing immaginario, or collective imagination, not restricted to the so-called high arts or letters, but very much also engaged with the everyday life, places, and tales we all constantly share. Many have spoken of how generous he was with ideas and suggestions, imbued with the underlying sense of a connective flux of shared thought. Ermanno Cavazzoni mentions in an interview published in the Corriere di Bologna not long after Celati had died, that many writers and artists owe something to him, but without strings attached of any sort, and without any stylistic diktats. As someone else very close to him said to me, he remained in many ways a man of simple pleasures who often surprised himself by what he had written, not driven by pride but rather a sense of wonder.

Celati was certainly not interested in fame, literary prizes, or prestige, and was in fact repelled by the conceit and bigheadedness that often accompany them. I think he was rather taken aback by all of the attention that his work attracted. He was instead drawn to that intense meeting place of ideas and identities wherein anything is possible and the sense of the individual self fades to the background. In an interview with Rebecca West he speaks of what he most admires in books: “allegria (light-heartedness, mirth), a kind of exuberance that can be mixed with pain, desperation, dreariness, even thoughts of death. The circus clowns Fellini filmed show that allegria in its mature form goes hand in hand with the acutest melancholy. Allegria is an expansive urge that does away with the gray indifference of the world, and few phenomena show so clearly the tendency of the individual human to project oneself beyond the self. In other words: allegria is a vital and basic way to go beyond the self, towards an exteriority of everything that we are not: things, stones, trees, animals, the spirits in the air and the darkness inside our bodies.”

Celati has certainly helped many to leap into various vivacious flows of ideas, places, and stories, and to feel part of a vast collaborative thought process that is never the work of any one person or small group. As he puts it in Verso la foce (Towards the River’s Mouth), “every observation needs to liberate itself from the familiar codes it carries, to go adrift in the middle of all things not understood, in order to arrive at an outlet, where it must feel lost. As a natural tendency that absorbs us, every intense observation of the external world carries us closer to our death—and perhaps also lessens our separation from ourselves.” Although Celati has died, his work contains a variety of mediations on death as an opening rather than a closure, something we often hide from or mask with kitsch or cheery appearances, and something inevitable that can bring us together, being that death too is part of our collective imagination. His work is full of an exuberant yet also understated courage, of an errant and insatiable curiosity, of an undying affection for others and other places. He will be missed by many, and his writings will undoubtedly continue to find new and varied readers, walkers, and thinkers.

I only wish that I had had the chance to spend more time with him, wandering who knows where and talking about who knows what, along the random mental and physical paths one stumbles upon with close friends, with small wonders at every turn. One of the few times I met Celati was in Cork, Ireland. His health had already started to decline, but he still had a slightly impish air about him, walking around the city with a sense of joy at simply being there, at one point crooking his arm around a light post and swinging slowly around to look back at me, the street, and us, smiling with wonder, a smile the vestiges of which I feel now on my own face.

It seems fitting to end with a few more of Celati’s words, drawn from the short reflective piece “Andar verso la foce” (“Heading to the River’s Mouth”): “If while wandering around I felt all day in a void, isolated from other people, in front of those forms of daily ritual there was born instead the fantasy of a connection with others—a connection even without approaching them, out of the idea that one can be connected to others despite also being completely isolated. It is the idea that everything that we do or think is part of a web that ties us to others, and that determines my gestures, the ways that I behave, what I want and what I don’t want. And the greatest connection lies in the fact that everyone I see out and about, everyone with whom I speak, is moving towards death, as if we were keeping each other company on this path.”

PATRICK BARRON is Professor of English at The University of Massachusetts, Boston, and has published a number of books of translations from Italian to English, including Celati’s Towards the River’s Mouth (Verso la foce): A Critical Edition (2018, Lexington/Rowman-Littlefield), Haiku for a Season, Haiku per una stagione, by Andrea Zanzotto (2012, Chicago), The Selected Poetry and Prose of Andrea Zanzotto (2007, Chicago), and Italian Environmental Literature: An Anthology (2003, Italica), which offered for the first time a comprehensive selection of Italian environmental literature from the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He has also published numerous scholarly articles, reviews, and poems, as well as the edited collection of essays, Terrain Vague: Interstices at the Edge of the Pale (2013, Routledge.) His collection of poetry Spooring was published in 2020 (Unsolicited Press).