10 Questions for Matt Donovan

- By Aviva Palencia

It could happen. Once it happens.

Earlier, later. Closer today

but not to you. You’ll survive

because you ran, because you hid.

Because you were first. Because last.

Because alone. Because the others.

—from “Mass Shootings Are Actually Pretty Rare, But Here’s What to Do If You’re Ever in One,” Volume 63, Issue 2 (Summer 2022)

What inspired you to write this piece?

For a few years, I’d been writing poems linked to guns and gun violence in America. While doing some online research into mass shooting preparedness, I stumbled upon an article in Self Magazine with a title that I borrowed verbatim for my poem: “Mass Shootings Are Actually Pretty Rare, But Here's What to Do If You're Ever in One.” I was stunned by the glib nature of the title’s phrasing (the implicit shrug of that “actually” is devastating, or at least it should be), as well as finding that article’s content in a mass-market health magazine accompanied by articles about firmer abs and weight loss. From the outset, the occasion for this piece became America’s normalization of our mass shootings.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

During the course of writing the poems in my forthcoming collection about gun violence, there were so many writers I turned to—John Murillo, Erika Meitner, and Matthew Olzmann, to name just a few—as well as the anthology Bullets into Bells. Because this particular poem focuses on survival strategies, I was reminded early on about Wisława Szymborska’s “Every Case,” an unforgettable poem about inflicted violence and the arbitrary nature of survival. With apologies to the Nobel Laureate, her poem’s strategies and fragmented syntax afforded a blueprint that I appropriated for my piece.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

I lived in Santa Fe for more than twenty years, so I’ve been looking at, and thinking about, the mountains of New Mexico for what seems like a long while. Meanwhile, I was born in Ohio, and still learning about all ways in which the Midwest and that place have shaped me. Somehow, your question also reminds me of a story about Brahms. He was once asked by a young apprentice about how to become a great composer, and Brahms replied “Take more walks in the woods.”

What did you want to be when you were young?

“Construction worker” and “astronaut” definitely topped the list when I was young, as well as any job involving a backhoe. When I was in high school, I was filled with romanticized ideas about being a writer of some kind, but after a lot of flailing attempts at short stories and even playwriting, I eventually found my way to poetry.

Tell us about one of the first pieces you wrote.

Those first poems I wrote were pretty miserable things—short-lined pieces cluttered with nothing but cloudy abstractions that must have sounded lush and “poetic” to my ear. I don’t really remember much about them, except they were all written to impress a girl at my high school. After I finally gathered the nerve to share them with her, she didn’t respond except to ask “In this poem, when you spelled ‘immense’ with two s’s, did you mean to spell it with only one?” I believe I had.

Do you have any rituals or traditions that you do in order to write?

I don’t really have rituals, except I’ve come to learn that, for me, continuity helps enormously. It’s as if I need to keep the piece churning in my mind each day to find the right path toward whatever it needs to be. If I’m lucky, taking some kind of swing at a piece every day will lead to a moment when I’m driving somewhere, not really thinking about anything, and out of nowhere I’ll find myself scrambling to find a pen and a stray scrap of paper in the car in order to write down some new line or approach. Whenever I’m endangering others from behind the wheel of my car, I know I may be getting close to finishing a poem.

Who typically gets the first read of your work?

My wife. I’m completely dependent on her insights and feedback whenever I’m drafting a piece.

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

When I was in college, I played tenor sax really, really badly, managing not much more than a lot of fierce squawking in the key of C. But despite my lack of skills, some of my musician friends would still let me play with them on the weekends, and I really loved those moments in jam sessions when the music seemed to cohere and could offer what felt like a cathartic release. As a writer who spends a lot of time alone while staring at the blinking cursor on my screen, I can sometimes still feel a little envious of those visceral moments of banging out music with friends.

What are you working on currently?

After writing a collection about guns and gun violence in America, I’m working on a number of different poems in which no firearms are mentioned, and no one gets shot.

What are you reading right now?

I tend to leap around in my reading and typically will have a number of books going at any one time. Right now on my bedside table, I have a number of poetry collections – new books by Ada Limon, Dana Levin, Erika Meitner – a graphic novel adaptation of Slaughter House Five, Srikanth Reddy’s Underground Lit, and Lily Hoang’s A Bestiary. I also just finished Lauren Groff’s Matrix, which I thought was such a beautiful novel.

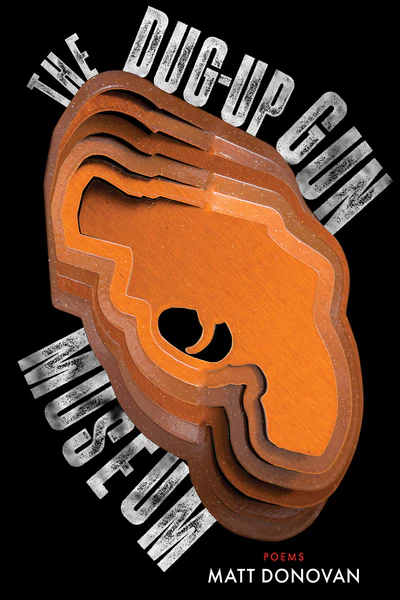

MATT DONOVAN is the author most recently of The Dug-Up Gun Museum (forthcoming from BOA in Fall of 2022) and the collection of lyric essays, A Cloud of Unusual Size and Shape: Meditations on Ruin and Redemption (Trinity University Press 2016). He is the recipient of a Whiting Award, a Rome Prize in Literature, a Creative Capital Grant, and an NEA Fellowship in Literature. He serves as Director of the Boutelle-Day Poetry Center at Smith College.