Zen and the Art of Actualizing Fiction

- By Ruth Ozeki and Michael Thurston

Editor’s note: On Wednesday, December 7, in the Paradise Room of the Smith College Conference Center, Ruth Ozeki gave a lecture titled “The Book of Form and Emptiness: Zen and the Art of Actualizing Fiction.” Provost Michael Thurston introduced the speaker, and his remarks follow here, as does Ruth Ozeki’s sabbatical report, mentioned in the intro.

Good afternoon.

For the last few years, I’ve begun introductions of speakers by introducing myself as “Michael Thurston, Provost and Dean of Faculty at Smith.” I am still provost and dean of faculty, but today I think it’s important that I introduce myself as a faculty member in the Department of English. This is because it is my great honor to introduce my department colleague, Ruth Ozeki, Grace Jarcho Ross 1933 Professor of Humanities.

I first got to know Ruth when she joined our department in a visiting capacity, as the Elizabeth Drew Professor. It was immediately apparent, to me and to my colleagues, that she brought something very special to the teaching of fiction writing, and when, after Ruth had been with us for a couple of years, we saw a path to welcoming her into the tenured faculty, we pursued that possibility with real enthusiasm. One of my first acts as incoming chair of the English department was to begin the process of a tenure review for Ruth. It’s hard to explain how easy and pleasurable it was to provide names of external evaluators for that case. I mean, we could survey the cadre of reviewers who had praised Ruth’s novels over the years, from My Year of Meats in 1998 to A Tale for the Time Being in 2013. Or we could tap the juries and committees that had considered her work and named her novels as New York Times Notable Books, finalists such prizes as the Man Booker and National Book Critics Circle award, and winners of prizes like the American Book Award, the LA Times Book Award, etc. We ended up hearing from an international array of esteemed novelists and critics, all of whom told us what we already knew: Ruth Ozeki is a simply brilliant weaver of narratives in which themes of crucial importance are developed by captivating characters and compelling prose. Hire, tenure, promote to professor? Slam dunk.

None of us who had read Ruth’s novels or witnessed her talks were surprised by this, but the ones who really just nodded and said “yeah, yeah, we always knew” were colleagues who had come to know Ruth not as an accomplished novelist but as a Smith College English major. It was a truth universally acknowledged, they said, that Ruth’s narrative and linguistic brilliance had already been on display when, as a graduating senior, she won pretty much every award the department gave for writing. And it is a legend that still reverberates around Seelye 105, where the department has met for years, that she spent her prize money on a motorcycle.

It is the productive tension crystallized in this anecdote that I think accounts for much that is so great about Ruth’s fiction. Her novels wonderfully balance the careful planning, plotting, and patterning attested by those prizes with the adventurousness and risk associated with that motorcycle. Think of the risks involved in giving objects voices, in focusing a narrative on a protagonist who hears and responds to those voices, on taking the existence of those voices, of that dispersed sentience, seriously (and not reducing them to symptoms or pathology). This is the risk Ruth takes in her most recent novel, The Book of Form and Emptiness, and she makes that risk pay off big through the care with which she constructs the character of Benny Oh, the relationship between Benny and his mother, Annabelle, and the plot that works out the problems established by and around these characters. Readers (and the judges for the Women’s Prize for Fiction) were moved and impressed by Ruth’s negotiation of the story prize vs. the motorcycle. If we all were not anxious to hear Ruth herself, rather than me yammering on about Ruth, I’d go into more detail about how we could analyze each of Ruth’s novels through the lens of the department prize and the motorcycle, but I want to get one more vital aspect of Ruth’s career into this introduction.

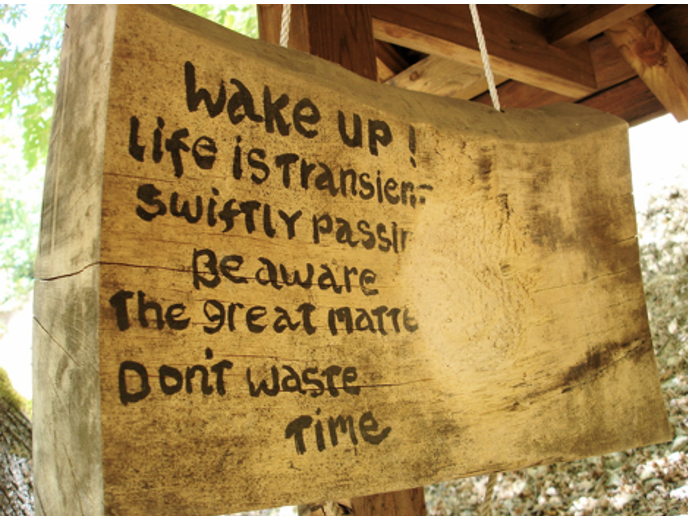

Another anecdote: as provost, I get to read every faculty member’s report on their sabbatical activity. Often, these are accounts of lab work completed, papers finished, manuscripts submitted, etc. They are impressive reading. Ruth’s report on her most recent sabbatical took a different approach and ended up being a ten-page illustrated essay on the experience of a Zen retreat in preparation for a next stage in her development as a priest. As much as any text I have ever read, this sabbatical report captured the real and often grueling difficulty of focusing on what is, on being fully present. It turns out that enlightenment involves a lot of carrot peeling and wood chopping. The challenges of presence are fully explored in Ruth’s nonfiction book, The Face, but I think her dedication to Zen Buddhism also informs Ruth’s approach to fiction. In her novels, we find exemplified and enacted a commitment to a mode of attention – constant, careful, compassionate, open, non-judgmental, detached from desired outcomes – that is a model and resource for any of us. I am grateful to Ruth for her work, for her career both before and here at Smith, for her presence, and for her example. Please join me in welcoming her to the lectern to deliver her chaired professor lecture, “The Book of Form and Emptiness.”

Professor Michael Thurston

Provost and Dean of Faculty

Smith College

July 21, 2020

Dear Michael,

I am writing to account for myself and my activities during my year-long Leave of Absence Without Pay. As you know, my vocational loyalties are divided between teaching at Smith, writing and publishing novels, and my practice as a Zen Buddhist priest. Over time, these three disparate callings have become increasingly congruent, so much so that at this point in my life, I cannot imagine one without the other, but while they are complementary and synergistic, they cannot always be practiced simultaneously. The year-long leave from teaching allowed me to engage with other two callings sequentially, to spend the first four months concentrating on Zen training, and then during the summer and fall, to switch my focus to the writing. My plan was to complete the next phase of my Zen training and to finish and revise a draft of my novel, “The Book of Benny Oh,” by the beginning of the spring 2020 term.

The Zen training I undertook was a three-month monastic residency at Tassajara Zen Mountain Monastery. I was ordained by my teacher, Norman Fischer, in 2010, and have been studying and practicing with him as a novice priest since then. During that time, I completed many of the training requirements, including short monastic residencies and periods of teaching. The final requirement was the three-month winter ango, or practice period, at Tassajara.

Ango, an ancient Zen Buddhist tradition dating back to the rainy season retreats during Shakyamuni Buddha’s time, is a ninety- or hundred-day training period, when practitioners make personal and collective commitments to intensify their Zen practice. Norman was the guiding teacher of the Winter 2019 Tassajara ango, and he asked me to come. Additionally, he invited me receive shiho, or dharma transmission, which, in Western Zen, represents the ceremonial completion of training and would enable me to practice as a fully empowered priest in the lineage.

Tassajara monastery is a secluded place, and during ango, monks practice entirely within this monastic enclosure, with little access to the outside world.  The physical conditions are primitive, and the ritual requirements stringent, so I spent much of December assembling the necessary gear, which included rain boots, rain gear, work clothes, long underwear, woolen socks, a down sleeping bag, headlamps, medicines, assorted kimono, undergarments and priestly vestments, ceremonial eating utensils, and sewing paraphernalia.

The physical conditions are primitive, and the ritual requirements stringent, so I spent much of December assembling the necessary gear, which included rain boots, rain gear, work clothes, long underwear, woolen socks, a down sleeping bag, headlamps, medicines, assorted kimono, undergarments and priestly vestments, ceremonial eating utensils, and sewing paraphernalia.

In early January, I flew to San Francisco and walked into a barber shop to have my head shaved. The barber was a middle-aged man with purple hair, dressed in a floral shirt, a vest, and bellbottoms. When I asked him to shave off all my hair, he refused. I explained the circumstances, that I was going to a monastery and that they wouldn’t let me in unless I severed my ties with the secular world by cutting off my hair, and finally he relented.

Tassajara monastery is located in Carmel, California. It is a small cluster of buildings clinging to the banks of a gushing creek at the bottom of a steep ravine, which can only be accessed on dirt roads in a four-wheel-drive vehicle. We traveled there in the middle of a torrential rain storm, which pretty much continued unrelentingly for the next three months. During this period, we lived in a community of seventy or so monks, getting up at three-thirty in the morning, sitting zazen for hours, studying Zen texts, listening to lectures, and training in the monastic practices that are necessary for a monk to know. Every aspect of monastic life is ritualized, with special forms required for the religious services held several times a day, the frequent and more elaborate ceremonies for memorials and special occasions, the sewing and wearing of robes and vestments, as well as for the daily activities of cooking, cleaning, bathing, using the toilet, and shaving the head.

What stays with me now is the rigor and totality of the practice, how isolated these communities are, and how physically demanding. There was no heat in most of the buildings, and the winter weather was extreme: torrential rains turning to snow, frequent flooding and landslides, and pervasive bitter cold. We could see our breath at night when we went to bed, and again when we woke in the morning. I slept fully dressed in a down sleeping bag, cocooned in layers of long underwear and scarves, with a woolen hat pulled down over my shorn head. In the zendo, where we spent most of our time, hats weren’t allowed.  I wore seven layers of undergarments beneath my Zen robes, which weighed about ten pounds when dry, but most of the time were heavier and wet from trudging up and down the flooded paths, shin-deep in mud. We washed our clothes by hand, wrung them out in an old-fashioned crank wringer and hung them up on a line, where often they froze.

I wore seven layers of undergarments beneath my Zen robes, which weighed about ten pounds when dry, but most of the time were heavier and wet from trudging up and down the flooded paths, shin-deep in mud. We washed our clothes by hand, wrung them out in an old-fashioned crank wringer and hung them up on a line, where often they froze.

Most of each day is spent in strict silence. We had no access to email or the Internet and there was no cell phone reception in the valley. We were allowed to line up to make short calls from a satellite phone during the rare periods of scheduled free time. The rains washed out the roads, so we went for weeks without receiving mail or supplies from the outside, including food staples like fresh vegetables, eggs, and dairy.

“What is Zen?” a young monk asks. “Just do the schedule,” his teacher replies. This is accurate. The monastery is the schedule. Monks live, breath, eat, sleep, and shit the schedule. Every minute of the day as assigned, from the first wake-up bell at 3:30 a.m. to the final bells at 9:00 p.m., with a few short scheduled breaks during which we could change our clothes or use the bathroom. Days of the month with four or seven (the 4th, 7th, 14th, etc.) were personal days, when the zazen and work schedule was reduced, and we received a few extra hours to sleep and exercise.

The han is the wooden time-keeping device that the monks strike with a mallet in varying rhythms and patterns to announce transitions in the schedule. From predawn to dusk, the rolldown of the han echoes through the valley. The day starts with several hours of zazen, followed by religious services and sutra chanting. Meals are served and eaten in the zendo to the accompaniment of drums and clackers and more chanting. The ritual of eating involves elaborate forms resembling those used in the Japanese tea ceremony. Every movement and gesture is choreographed: the way chopsticks are taken from their sleeve, the way a spoon is placed on the mat, the order in which the bowls are nested and the napkins folded. Servers come around at precisely timed intervals, and all communication is done in silence using specific hand gestures, meaning Yes, please, No, thank you, A little more, Enough. The meal itself must be eaten and the bowls emptied in six minutes.

The han is the wooden time-keeping device that the monks strike with a mallet in varying rhythms and patterns to announce transitions in the schedule. From predawn to dusk, the rolldown of the han echoes through the valley. The day starts with several hours of zazen, followed by religious services and sutra chanting. Meals are served and eaten in the zendo to the accompaniment of drums and clackers and more chanting. The ritual of eating involves elaborate forms resembling those used in the Japanese tea ceremony. Every movement and gesture is choreographed: the way chopsticks are taken from their sleeve, the way a spoon is placed on the mat, the order in which the bowls are nested and the napkins folded. Servers come around at precisely timed intervals, and all communication is done in silence using specific hand gestures, meaning Yes, please, No, thank you, A little more, Enough. The meal itself must be eaten and the bowls emptied in six minutes.

Four or five hours of each day are spent doing manual work of some kind. Upon their arrival at the temple, monks receive their assignments, which include kitchen work, groundskeeping, zendo maintenance, and general labor. I was assigned to the kitchen, where I washed dishes, scrubbed the floors, sorted beans and legumes, and chopped hundreds of gallons of carrots, celery, broccoli, cauliflower, kale, chard, brussels sprouts, cabbage, garlic, and onions. Always more onions. Sometimes I was allowed to cook. Once, for a special celebration, I made fifty pizzas. In the afternoon, at the end of every period of work, we had a blissful ninety minutes of time to exercise and bathe in the hot springs.

The Zen lifestyle is not what people think. Hot springs not withstanding, there is little in the monastic life that is relaxing, peaceful, or contemplative. Zazen is grueling. Work is grueling. Attendance is taken for every activity, and permission from a teacher is required to miss a meal or a period of work or meditation. Monks are sleep-deprived and hungry, and mentally, physically, and emotionally spent. Grievances simmer and interpersonal conflicts abound. Day after day, minute by minute, you are forced into confrontation with your resistance to what is happening. You are brought face-to-face with your likes and dislikes, your attachments and aversions, and eventually holding on to these is simply too exhausting and you give up. Then, for a brief moment, your preferences drop away, and you are left with a profound sense of peace and contentment with what is. Just this. Then the cycle starts again.

Just before I arrived at Tassajara, I spoke to Norman about postponing my transmission. In the monastic community, shiho is a big deal, the equivalent of receiving a graduate degree, and many teacher expect their novice priests to spend years in monastic residency before deciding they are ready. I felt grateful to Norman for his willingness to empower me, but I was having doubts. I wanted to experience the ango and monastic life without the pressure of shiho and all the consequent expectations and projections, my own as well as those of the community.  In Zen literature, Great Doubt is celebrated, and I needed more time to struggle with mine, including my doubts about the merits and dangers of organized religion, and the hierarchical and hegemonic institutions of Zen that are manifest even in laid-back California. Norman agreed and allowed me to defer. He invited me to join the study group with the other shiho candidates where we read the Dogen teachings on transmission, and to participate in many of the ritual preparations for the event. This gave me a chance to observe and understand a bit better what this ancient tradition entailed, and in the end, I was glad I’d deferred. I’m still grappling with my doubts and probably always will, but maybe during my next sabbatical, I’ll be ready.

In Zen literature, Great Doubt is celebrated, and I needed more time to struggle with mine, including my doubts about the merits and dangers of organized religion, and the hierarchical and hegemonic institutions of Zen that are manifest even in laid-back California. Norman agreed and allowed me to defer. He invited me to join the study group with the other shiho candidates where we read the Dogen teachings on transmission, and to participate in many of the ritual preparations for the event. This gave me a chance to observe and understand a bit better what this ancient tradition entailed, and in the end, I was glad I’d deferred. I’m still grappling with my doubts and probably always will, but maybe during my next sabbatical, I’ll be ready.

After leaving the monastery, I spent the spring semester working on my novel and growing my hair. In May, I did a writing retreat at Hedgebrook, a women’s writing center on Whidbey Island, where I have served on the Creative Advisory Council for many years. I taught at Vortext, their annual writers conference, for several days and then spent two weeks in residence. Hedgebrook was the opposite of the Tassajara, with nothing but unscheduled free time for writing, and lots of wine and conversation at dinners that I did not have to cook. I returned to Northampton, refreshed, and spent the rest of the spring and summer working on the novel, now titled “The Book of Benny Oh.” I finished a draft in August of 2019, sent it to readers and to my editor at Viking. Since then, I’ve been working on revisions based on the notes I received. It’s been slow going, made slower by the upheaval of the pandemic, but now it’s almost done. I hope to deliver the final draft at the end of August, 2020.

I didn’t plan to write a photo essay for this Leave Report, but I guess my role as a creative writing instructor entitles me to some artistic license as I reflect on the Leave and what I learned from it. During the monastic residency, I spent a lot of time contemplating the role of ordeal in a person’s life and what it can teach us. In traditional cultures, coming-of-age ceremonies often involve a ritual ordeal of some sort to mark important transitions in a young person’s life. I am not young, and I live in a secular consumer culture that looks at ordeal as something to be avoided at all costs. When something happens that doesn’t suit my liking, I can usually buy or otherwise obtain relief from my discomfort, and I do so unthinkingly. So what role does ordeal serve in my life?

The monastic residency was an ordeal, one of the hardest things I’ve ever done, but it was an ordeal that I chose. Its discomforts only lasted three short months, and by the end there was much I’d grown to love about the community and the lifestyle. Writing a novel is also an ordeal, especially when it drags on as long as this one has, but again, it’s a struggle of my own choosing, and not without its joys and pleasures. Like all ordeals, these two have had a tempering effect, by requiring a certain amount of resilience, forbearance, negative capability, and the wherewithal simply to be with what is. In the moment. Just this.

But that was then, and this is now. I’ve been thinking about the phrase “just this” a lot in recent months, as the COVID pandemic drags on, disrupting my easy assumptions about discomfort, struggle, and suffering. The pandemic is an ordeal none of us expected. We didn’t choose it. We couldn’t plan for it. It’s testing our resilience, forbearance, and our ability to be with uncertainty, and we are being found wanting. I hope this changes. I hope we survive this ordeal and it makes us stronger.

I wish I could say that as a result of my leave, I feel equipped to handle the challenges we face this fall, but I don’t. I don’t think anything could have prepared us for an ordeal of this magnitude, and my struggles have been minimal compared to what so many others are suffering. Still, as we move forward, it’s been helpful to me to mull over what I’ve learned during the past year, and I appreciate having had this occasion to do so, as well as the opportunity to express my thanks. I am very grateful to the College for giving me the time away, and even more for giving me a place, a job, and a community to come back to.

Michael Thurston is a former Prose Editor and Reviews Editor for the Massachusetts Review and Provost and Dean of the Faculty, as well as Helen Means Professor of English Language and Literature at Smith College.

Ruth Ozeki is a writer, Zen priest, and author of My Year of Meats, All Over Creation, The Face, and A Tale for the Time Being. Her latest novel, also described here by its working title, is The Book of Form and Emptiness. She teaches creative writing at Smith College, where she is the Grace Jarcho Ross 1933 Professor of Humanities.