10 Questions for Clare Richards

- By Edward Clifford

Five minutes later and I was already regretting going with him. I fell behind, uneasy. I hoped he wouldn't notice, that he'd carry on walking. But he stopped and turned around. It seemed he wouldn't move an inch until I was right beside him. His smile read catch up, quick. I told him to go ahead, that I'd follow.

—from "The Lake" by Kang Hwagil, Translated by Clare Richards, Volume 63, Issue 4 (Winter 2022)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you translated.

I first started out translating film subtitles. My most memorable experience was working on 1990 documentary Even the Blades of Grass Have Names, the first work by South Korean feminist film collective Bariteo. The film takes a very candid, yet humorous, look at the lives of female office workers and the labor activist movement in Korea at the time. It was screened two years ago in London, but I still often think about it.

I focus mainly on literature now. Once I made the move over into novels, I found the translation process so much more satisfying. With film and TV subtitles, information needs to be conveyed quickly and effectively in just a few words displayed on the screen for only a few seconds, which inevitably leaves you somewhat restricted stylistically. My urge to create perfect, beautiful sentences had to take second priority. With literary translation, I don’t find myself with these same constraints. That is, of course, no criticism to the art of subtitle translation, which is an incredible skill.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

If there were one writer I’d really like to emulate, it’d be South Korean novelist Kim Keum Hee. Every single one of her sentences is immaculate. I see her prose like a game of Tetris, with each part of the sentence as one of the blocks, which all fit together precisely and exactly, without leaving a single hole. Kim makes such intelligent and insightful observations on human nature, and she crafts her characters with so much depth and compassion. I’m pitching a translation of one of her novels at the moment, and her writing is a sheer pleasure to translate.

What did you want to be when you were young?

A vet—though I soon gave up on that idea once I realized it didn’t align too well with my squeamish side. I don’t have many grand goals in life, but my one hope is to eventually save enough for my own place in the countryside, with a few cats to keep me company.

What drew you to write a translation of this piece in particular?

There’s something about Kang Hwagil’s stories—they just stay with me. The Lake is one of those stories you can read again, and again, and it’s still just as eerie, and just as impactful. The way Kang captures the relentless tension between fear and self-doubt experienced by the protagonist—it’s almost suffocating. The Gothic is probably my favorite literary genre, and so I was inevitably drawn to Kang Hwagil’s work. Kang is heavily influenced by 19th and 20th Century Gothic women writers such as the Brontë sisters, Mary Shelley and Shirley Jackson, and she is (as far as I’m aware) the only South Korean novelist who writes explicitly within the genre

Is there any specific music that aids you through the writing or editing process?

I work in silence. Or, if I am forced to work in a noisy place, I wear my noise-cancelling headphones and listen to music without lyrics.

Do you have any rituals or traditions that you do in order to translate?

Autism, for me, means routine is everything. One of the things that works so well for me about the freelance lifestyle is the level of control it permits—over when, where, and how I work. I almost always prefer to work at home, where it’s quiet, I can wear my comfiest clothes, and can have the temperature, lighting, and so on, exactly how I like it. When I was living in Korea, I also liked to occasionally work in cafes (Seoul café culture is next level), but it’s very difficult to find places here that don’t have a problem with customers ordering a coffee and setting up camp for a few hours (which is completely the norm in Korea).

Who typically gets the first read of your work?

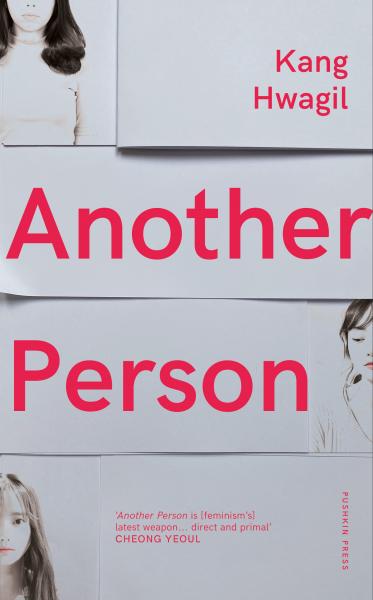

While I was mentee for the UK National Centre for Writing Emerging Translators Mentorship Programme, my mentor Anton Hur was always the first person to read my work. Since then, I often ‘swap’ pieces with other translators for editing. The process is so beneficial for my translations, as well as my editing skills, and is also wonderful in the community it builds (translation can otherwise be such a solitary endeavor). Arabic translator Sawad Hussain has read so much of my work, including my entire translation of Kang Hwagil’s novel Another Person, which will be published by Pushkin Press in the UK in June 2023.

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

Photography. I’m very much a ‘visual’ person, and have always loved taking pictures. I think it’s the way photography combines visual creativity with the technical aspects of the camera—you could say I have a very ‘logical’ approach to creativity. Rather than creating something from scratch, with photography you are taking what you see in front of you and interpreting it in your own way, before using the camera as a tool to represent that as best as possible. I find a similar appeal in translation—creativity, but with an existing basis or framework from which to create. A creation that is a reinterpretation of something that already exists. In the same way that ten different photographers will take ten different pictures of the same object or scene, ten different translators will produce ten different translations of the same source text.

What are you working on currently?

One of the writers I am currently translating is South Korean poet and novelist Lim Solah. I am working both on her most recent short story collection and her first (and only) novel, The Best Life. The Best Life tells the story of three young girls who decide to run away from home together, and is an untangling of the recurrent nightmare that plagued Lim (who ran away as a middle school student herself) every night for twenty years since her teens. I am very strongly draw to Lim Solah’s raw, stripped-back prose. Just like Kang Hwagil’s gothic tales, there’s an ever-present tension and foreboding, and there is a direct and confrontational quality to the writing that leaves the reader unable to escape the violent reality faced by the novel’s vulnerable young heroes. The book is still looking for a publisher, but I’m really excited to (hopefully) introduce it to English language readers one day.

What are you reading right now?

My currently-reading list is always a little chaotic. A lot of my reading is for research purposes—whether that’s for understanding the current English-language literary market and thinking about where to pitch my next translation, or for seeking out works in Korean I might like to translate—but of course I read for pleasure, too. I’ll also have at least one or two audiobooks on the go (for before going to sleep, and whilst I’m driving, cooking, cleaning, exercising, etc.). Then there are the books I’m reading for my translation swaps and editing work. I’m currently reading and editing Sawad Hussain’s translation of South Sudanese author Stella Gaitano’s novel Edo’s Souls, which won a PEN Translates Award and will be published by Dedalus Books in the UK in May 2023. It’s a historical multi-generational epic that follows one family through the coups and counter-coups of the seventies and eighties in what is now Sudan and South Sudan. It’s a truly sensational novel (and translation) that I cannot wait for people to read!

CLARE RICHARDS is a neurodivergent literary translator based in London. She has a particular interest in feminist fiction, and her upcoming publications include Kang Hwagil’s gothic thriller Another Person (Pushkin Press) and Park Min-jung’s short story "Like a Barbie" (Strangers Press). In 2022 Clare founded the D/deaf, Disabled and Neurodivergent Translators Network, and she also leads the UK Society of Authors Translators Association Committee Accessibility Working Group.