10 Questions for Valerie Sayers

- By Franchesca Viaud

Valerie Sayers

Valerie Sayers

"I tell Rudy that we really really need a new mattress and watch his mouth twist—he's never thrilled about buying anything, much less a mattress that might take as long to pay off as a new car. The old one was supposed to last twenty years, and Rudy's hell-bent on getting every last night. But honeybun, my aching back and the yellowing receipt agree: the twenty years are up."

—from "I Don't Need It, I Just Want It," Volume 64, Issue 3 (Fall 2023)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you wrote.

Like most writers, I’ve been at it a lifetime, but the first consequential work I produced came when a high school teacher assigned Light in August and then asked us to write in a Faulknerian voice. I don’t remember anything about the themes I decided to explore (pregnancy? racial identity?), but I do remember in every writing bone the exhilaration of channeling the Great Man in all his idiosyncratic glory.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

Faulkner, for sure; as a Southern writer, I spent years learning how to step out of his shadow and Flannery O’Connor’s, too. Eudora Welty, Toni Morrison. George Eliot, Dickens, Balzac, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Turgenev, Chekhov, Isaac Babel. Edith Wharton, E. M. Forster. Kafka. Vonnegut, Böll, Coetzee, Gordimer. Walker Percy, J. F. Powers, James Baldwin, Marguerite Duras, Manuel Puig. Hilary Mantel. Muriel Spark, perhaps more than anyone else on this list. But it’s impossible to stop there. Maxine Hong Kingston, Robert Stone, George Saunders, Louise Erdrich, Roberto Bolaño, Colson Whitehead, Elena Ferrante, Zadie Smith, Sigrid Nunez, Edward P. Jones, Jaimy Gordon, Kevin Barry, Alice McDermott, Melanie Rae Thon. So many good writers on this earth, and I’ve only just started on the prose writers. So many poets and playwrights and composers and visual artists and screenwriters and directors still to name, too, because they influence how I write too; so many more novelists and story writers I’ve gleefully imitated and stolen from.

What other professions have you worked in?

I’ve been a waiter (I was a klutz); a copy-taster for Reuters (don’t ask, though it was a wonderful job title, as interesting as sin-eater); an editorial type doing a little of everything; and a teacher. You might say I also worked in childcare as mother to two children who taught me a great deal about focus and delight.

What did you want to be when you were young?

What did you want to be when you were young?

An actor. I was the designated writer in my family and, though I secretly thought of myself that way too, I resisted a role that I thought would involve a lot of solitary and frustrating failure (I was right about that). I took off to New York bound for stardom, a notion that I was disabused of in about three days. Ironically, seeing how tough a life the theater is made me finally declare myself a writer, an art form wherein the odds of rejection are also, shall we say, high.

What inspired you to write this piece?

Online shopping for a mattress (on the web, American consumer culture is more stupefying than ever). And contemplating, as we all do now, the rising waters and our changing attitudes toward sex and gender.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

The town in this story, Due East, is where most of my novel writing, and some of my story writing, is focused. It’s a thinly disguised Beaufort, South Carolina, where I was born. I left Beaufort for New York when I was seventeen, and spent the rest of my adult life homesick. Largely because I’ve always felt so ambivalent about the beautiful, racist, warm, stratified place where I grew up, place has always been a big driver of my work. When I started writing about Due East in grad school, I grandly called it my “moral landscape,” though immoral may be more like it. I’ve also written about the struggles of making rent in New York, where I lived for twenty-odd years; the strange and scrappy Midwest, where I moved when I began teaching at Notre Dame; various spots in Ireland, my ancestral home and dreamscape; and places that just intrigue me, like New Orleans.

Do you have any rituals or traditions that you do in order to write?

I almost always take a long walk before I write—the free-flow of language that walking releases in my mind often becomes the first hour of writing.

Who typically gets the first read of your work?

I send stories and essays out directly to an editor or agent without giving anyone else a look. I hope that by now I’m my own toughest critic. But for longer manuscripts I sometimes rely on another writer for help, and no two have been more helpful than my lifelong friend Liz Dowling-Sendor and my Notre Dame colleague and friend William O’Rourke.

What are you working on currently?

I’ve written a lot of stories in the last year (a lot for me, anyway) and I’m also working on a manuscript called “Sin, Sex, and Segregation,” about growing up in the Jim Crow South and leaving it. The title comes from the great Southern gadfly Lillian Smith, one of the most forceful white writers of her time and one of the few who consistently highlighted racial injustice.

What are you reading?

I’ve just finished Quitman Marshall’s wonderful Swampitude, a mesmerizing meditation on swamps and family history. I alternated chapters with poems from Kevin Ducey’s new collection, Gravity’s Angel, a series of wild and sublime poetic commentaries on Simone Weil’s activism and thought. Before that, I tore through four Anne Enright novels, all deft, all deceptively light as they begin but complex and satisfying by their endings. I am just dipping into Colson Whitehead’s Crook Manifesto; I found Harlem Shuffle delightful. I sometimes feel I’m most myself when I’m immersed in a novel, whether I’m writing it or reading it.

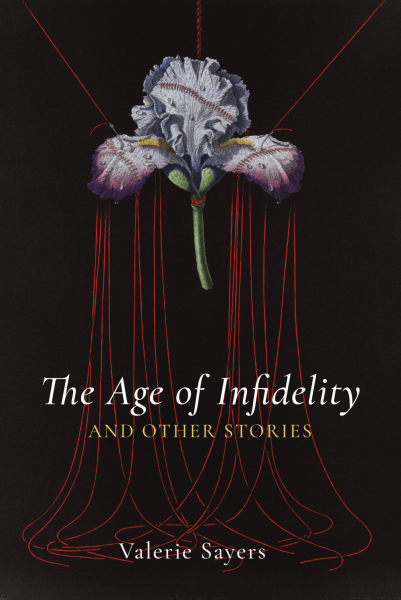

VALERIE SAYERS is the author of six novels, including The Powers and Brain Fever, and a collection of stories, The Age of Infidelity. Her books have been on many “Best of the Year” and “Editors’ Choice” lists, including those at the New York Times, Washington Post, and Chicago Tribune. Other literary honors include an NEA in fiction and two Pushcart Prizes. Her stories and essays appear widely. She taught for many years at Notre Dame, where she was Kenan Professor of English and founded the Notre Dame Review.