Living Documents: An Interview with Vauhini Vara

- By Chaya Bhuvaneswar

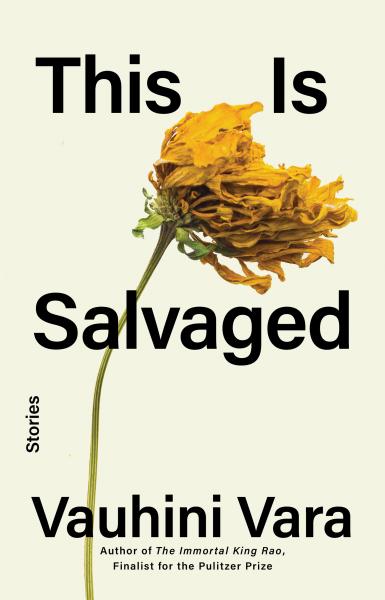

/index.jpg) Author Vauhini Vara

Author Vauhini Vara

Chaya Bhuvaneswar: Tell us the journey of how you came to write the stories in this wonderful, unsettling collection. Were there some that came quickly and others that took more time?

Vauhini Vara: For me, everything I write feels like a living document, up until the time it's published in a book, and I’m no longer allowed to change it. I love going back into the same pieces over and over, getting them closer to what they’re meant to be. I began writing about half of these stories in 2008, when I entered graduate school. At the time, I didn’t conceive of them as belonging to a collection because I was just starting out as a writer. The revision process was really long—ten to fifteen years—for all of the stories I started during that period. However, there are a few stories in the collection that I wrote more recently and more quickly. For example, “The Hormone Hypothesis” is the newest one; I started it last year.

CB: Buses, smells, disintegration, loss, and decay. Were you aware of these themes uniting several of the stories? Why do you think these permeate the book?

VV: With disintegration, decay, and loss: yes. With buses and smells: no. So I can speak more clearly, probably, to the first three as themes in my stories. I was interested in the boundaries between oneself and others, how those boundaries are porous. Writing about life—of humans, animals, plants—in decay was a method for manifesting the ways in which those boundaries can be dissolved (flowers literally lose their petals; humans literally lose our hair, our skin). And death is of course the most explicit possible form that this decay can take.

CB: What is your take on sarcasm, generally? In my reading, there is some kind of connection, in your stories, between sarcasm and the speculative. As if sarcasm somehow lightens the permanence or stability of what exists, opening up the possibility for objects and people that seem to expand reality. The cannibal stories. The child with the imaginary grenade. The burned and salvaged wood of the self-made artist. But on the other hand, sarcasm can be used as a defense—to hide hurt feelings, to hide any feelings. Do you feel it is deliberately used by your characters to do this too? Why are they afraid to show their unfiltered feelings?

VV: I don’t know that I have a particular take on sarcasm except to say that, as far as forms of expression go, it’s versatile—it can allow people to be honest and vulnerable while also self-protective to an extent. And I think that’s how a lot of characters in my stories deploy it.

CB: I loved how there was a sense of a continuum in your stories between the speculative and climate change. Recycling, salvaged, etc. This is a reminder of larger concerns elsewhere in your writing—where technology, consumption, science outstrip our capacity to cope. Can you talk about these ideas in your work across genres and what relationship, if any, your novel has to these stories?

VV: Yes, that’s true! Maybe because I have a background as a business reporter, or maybe just because I live in a world threatened by capitalism’s growth imperative, I can’t help but be aware, in my work, of capitalism’s pervasive influence. I’m glad you noticed that, because some readers have said they feel the stories in This is Salvaged don’t share The Immortal King Rao’s same preoccupations. I intended for the subject to be very present in This is Salvaged, but less explicitly so: while the novel’s titular character plays a major role in shaping capitalism’s influence in an imagined future, the stories focus on people living in a more-or-less realist present-day world under the influence of capitalism.

CB: In “You Are Not Alone,” I found the shifts in perspective extremely moving. What led to your writing this story from multiple POVs—little girl, father, father’s new girlfriend? It was also both subtle and striking how much of a contrast there was between the Brazilian girlfriend’s actual (deep and compelling) thought content vs. the trivial and irrelevant perspective that the girl attributes to her, for example, here: “The girl thinks the stranger might be the kind of person who thinks differently colored M&Ms taste different, even though they don’t.”

VV: That story is written in the third person. It starts with the close third-person perspective of a little girl visiting her father and his new partner—focusing on her own feeling of distance between herself and those around her—but then, toward the end, we enter the perspectives of her father and partner as well. My goal was to show how the human experience of that feeling, we can call it loneliness or isolation, is actually a shared experience. Sometimes when we feel alone, we imagine that everyone around us is interconnected and that we stand outside of all that. But it’s more likely that the others around us are experiencing a version of that feeling as well. It’s just that our own isolation prevents us from seeing it and reaching out beyond ourselves.

CB: Your characters are often deeply irreverent. Yet Buddhism and spirituality repeatedly surface. Is there a spiritual or religious vision that informs your work? I’m thinking, too, of the essay “Ghosts,” which to me (as an actively, deeply religious person) felt spiritual. Or at least, aligned with the spiritual.

VV: I’m not religious. But my stories, as well as that essay (which ran in The Believer), are absolutely interested in religion and spirituality as ways to understand the world. The narrator of the story “The Hormone Hypothesis” puts it well, “I love talking to people who believe in God. I love their perspective, it sounds like a poem to me, their religious language. I admire their willing submission to that which is most mysterious in life.”

CB: I found it so moving that your sister had written the poem included in one of the stories. On the level of craft, how is it different addressing the loss of her in fiction vs. essay? Are there details you would want to portray only in fiction, and do you think fiction affords emotional protection around that loss?

VV: I tend to be a private person and love being able to tell the truth under the guise of fiction; it does feel self-protective. There certainly are experiences from real life—and I won’t say what they are!—that I would never write about in my nonfiction but would fictionalize. That said, being a journalist by trade, I understand the value and appeal of nonfiction stories; specifically, the way in which acknowledging that a piece of writing represents the literal, actual truth (or a version of it, in any case) automatically raises the stakes. Personally, I love writing and reading both forms.

CB: What are you working on and reading now? What else can we look forward to seeing from you soon?

VV: At the moment, I’m reading The Patriarchs by Angela Saini, a work of science journalism that is blowing my mind. I just finished Blackouts by Justin Torres and Terrace Story by Hilary Leichter, both remarkably original, and A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Gríofa is up next! Speaking of nonfiction: I’m currently writing essays. My essay “Ghosts,” along with others and including this recent one in Wired called “Confessions of an AI Writer,” will be compiled into a collection of tech-related essays, edited by Lisa Lucas and published by Pantheon, in early 2025. My deadline is in January, not too long after my book tour!

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

CHAYA BHUVANESWAR is a practicing physician, writer and PEN /American Robert W. Bingham Debut Fiction award finalist for her story collection WHITE DANCING ELEPHANTS: STORIES, which was also selected as a Kirkus Reviews Best Debut Fiction and Best Short Story Collection and appeared on "best of" lists for Harper's Bazaar, Elle, Vogue India, and Entertainment Weekly. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Salon, Narrative Magazine, Tin House, Electric Literature, Kenyon Review, Masters Review, The Millions, Joyland, Michigan Quarterly Review, The Sun, The Awl, and elsewhere. She has received fellowships from MacDowell, Community of Writers and Sewanee Writers Workshop. She is currently at work on a novel.