10 Questions for Lory Bedikian

- By Franchesca Viaud

%20web%205x7%20(1)/index.jpg)

After we make love, I think of the word obliterate

how it means the destruction of something. I think

hostile hands are everywhere. We should probably

nail it all shut. I don't have time to think back to

the fourteenth century because too much is tangling

roots this day and the day after.

—from "Manifesto,'" Volume 64, Issue 4 (Winter 2023)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you wrote.

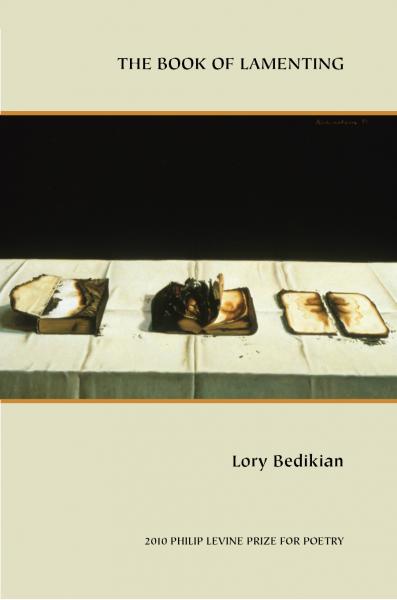

Well, I’ve been writing for decades so I wouldn’t be able to do that. Let me bring back a poem I worked on revising during my MFA. It was a century ago, the year 2000, and I presented something to the workshop group titled “Beyond the Mouth,” which is now the opening poem to my first collection, The Book of Lamenting. The reason I’m bringing up this particular piece has much to do with something that was said by a young man during the workshop and fortunately or unfortunately the statement has stayed with me these — wow — 23 years. He said the poem was not “believable.” This is because I put a dove on the back of every one of my family member’s tongues and the poem claims that the doves live and die there. Not believable? I look at the world today, 23 years ago, every day in the inner-cities, I look at poverty, sexism, ageism, racism, the beginning and end of each century, war for land, money…I almost forgot what I was talking about. Yes, I guess nothing is believable. Maybe the young chap was right.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

In order to avoid spiritual nausea, I want to patrol myself from unnecessary name-dropping, or “billboarding” so I’ll begin with those who have passed on — part of those in my poetic genealogy. When I first read Adrienne Rich I was good-afraid. I told myself if I could be that brave, it would be outrageous and wonderful, but I didn’t want to be disowned — back then — by my parents. I have always loved what Eavan Boland said in an essay once about the danger in writing from platforms. (I’m sure I got that wrong). I have always been in love with her quiet excavation of the ancestral/female voice. The teacher-poems come from Gwendolyn Brooks, Audre Lorde, Anna Akhmatova, Muriel Rukeyser, Wanda Coleman, Shushanik Kurghinian, Wisƚawa Szymborska. O.K. Khalil Gibran, Pablo Neruda, Philip Levine. And it’s not necessarily what they write about, style or irreverence but that they wrote despite what was going on with the outer and inner worlds. This is obviously not a complete list.

What other professions have you worked in?

So, I already said the word decades, so no one should be in shock or think that I’m making this up. I’ve had more jobs than professions. I was maybe 15 or 16 and I started working at a beauty supply store and beauty salon. I’ll mention what may interest readers because the filing jobs, the punch-in-the-numbers jobs where I’m at the water cooler talking crap about injustices in the workplace and in the world may not be as intriguing. I was a copyeditor, proofreader for a newspaper and worked the night shift while going to UCLA for my undergraduate work. For a while I worked at a photography studio answering phones, cleaning bathrooms, organizing film into envelopes, moving around papier-mâché columns, that type of stuff. After graduating, I worked at a newspaper group selling advertising, but moved to becoming a restaurant and theater reviewer. Things went wrong at the newspaper group. Fast forward to post-MFA. I was fortunate to receive a Graduate Teaching Fellowship at the University of Oregon which paid off my schooling. The trade was teaching the entire two years. I also applied to teach the summer session and was granted that job. I loved teaching. After the MFA, I moved back to southern California with a false hope that the two years of teaching would help me land the teaching job of my dreams only to find out that if I became a “freeway flyer” and turned my trunk into a makeshift office I could teach composition across the map of Los Angeles. The breaking point was when one college scheduled me for an 8 a.m. and a late afternoon class and there was nowhere conducive to meeting students, correcting papers and it would have taken an illogical drive back to where I was living…oh, this is not interesting, so I’ll stop there. My full-time professions now include motherhood and teaching poetry workshops independently. My full-time dream is writing poetry.

What did you want to be when you were young?

What did you want to be when you were young?

A poet. When I was eight I told my parents I was meant to be a poet. I told my mother if you want I can be an actress like Doris Day. I told her I have the talent. I told my father I can be an opera singer if you want. And then I wrote poems.

What inspired you to write this piece?

Beforehand, I want to thank Massachusetts Review for selecting, allowing these pieces/poems to be part of something so necessary: “Revisiting WOMAN: An Issue, 50 Years Later.” This special issue is a genius, stellar idea. I’m really honored to have these poems in the conversation.

After many renderings of “Ode to Illness: Rant in the form of monologue” the original draft finally found its voice when realizing I was doing to the poem what my familial construct had done to the little girl version of myself. The pattern repeated when as a young woman I was told not to tell the relatives of any diagnosis I may have been informed of. My voice for years had a feeling of being banned. One suddenly realizes there is a fine, weak thread between illness and being constantly silenced. The revelation allowed me to go beyond a mere ode of description to a public art piece that is both revelatory and necessarily ugly. The poem began as a reaction to being diagnosed with disease. The poem became art when it grasped at the collar asking “why was I made to be quiet?”

“Manifesto” was written post-intimacy, but then I suddenly realized I had read long, long before Galway Kinnell’s “After Making Love We Hear Footsteps.” I thought well, the man has spoken. This has been written before. Blah, blah, blah. Then I did research and found the Terrance Hayes poem “God is an American.” Maybe I was rushing, maybe I just needed to read more, but I couldn’t find a female voice speaking of the thoughts that arise in those after-love moments. I’m sure there are, and I’m sure they are being written as I write this. I mention all this to say, something kept me from giving myself permission to write my own version. Something elbowed me, brought up what I need to do, not do, a lot of brain-chatter, but I thought why am I orphaning this thing that I have written? Why am I ashamed to write and revise such things? Revising “Manifesto” toward what it is today was the way I allowed all the years of searching for a feminist perspective to take a bit of action.

Is there any specific music that aids you through the writing or editing process?

Not while I’m writing or editing/revising. I need complete quiet. I wear earplugs if possible. Noise pisses me off. That’s probably because I grew up sharing a three-bedroom home with seven people. I shared a bedroom with my grandmother and aunt until I was around 16. Two older brothers, parents. My grandmother and aunt were expatriates from Aleppo, Syria. There are so many of their sounds I miss now. To be precise, I miss my grandmother’s singing, her mumbling prayers and the clicking sound her dentures made. When I’m not writing…music is the major healer, the inspiration when coffee and the world stinks. R&B/Soul, jazz, classical, punk, Latin jazz, cumbia, folk, rock, crappy radio songs. I wrote a poem about radio songs, but it didn’t make the cut to be included in my second book.

Who typically gets the first read of your work?

No one. I (mistakenly) feel too confident and then I send the work out and nothing happens. I’m laughing as I type this. Then, when I reach for the humility canister, behind the cupboard of false-confidence, I read it to my husband, the poet William Archila. Basically, he’s honest. He’s not influenced by what everyone else is doing, thinking, writing. He’s real.

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

Punk rocker. Cellist. Acting, playwriting, photography, sculpting, painting, installation art, graffiti, gardening, garden design, public park design, clothing design, dancing, jewelry making, clothing, shoes, cooking (though I hate preparing meals), singing, bass guitarist. I really don’t want to stop this list. Pottery. Constructing monuments to activists. Reforesting the planet. Maybe a punk rocker who plays cello and plants trees full time.

What are you working on currently?

I’m working on the publication process for my second book “Jagadakeer: Apology to the Body,” which recently won the 2023 Prairie Schooner Raz-Shumaker Book Prize in Poetry and is forthcoming September 2024 from the University of Nebraska Press, for which I am immeasurably grateful. A group of phenomenal people gave these poems a chance. And then, you know, you just keep writing in response, in protest, in reaction, reflection. So, I’m working on a few things at once. I’m trying to mend something that can’t be mended by working on a series of poems attempting to protect the endangered Western Armenian language. But then I see women underestimating the natural beauty of their bodies, I hear children saying things they shouldn’t have to say and I respond in poems. I’m also trying to see what to do with the dozens of poems that weren’t used in the second book. I mean, here’s the math. My first book won the 2010 Philip Levine Prize for Poetry and was subsequently published in 2011. The second book won in 2023, is being published in 2024. Thirteen years. The reasons would fill a whole other interview! The main thing I’m trying to say is that because of that major delay, the second book was either going to be a selected, a collected, but I went with what truly is going on with my voice, the poems, the need at this moment in time. My need in response to my inner world, the outer world.

What are you reading right now?

Saving myself from reading toxic food labels, pharmaceuticals bottles, I’m going back and looking at Anatomy of an Illness: As Perceived by the Patient by Norman Cousins and currently I’m rereading Wanda Coleman’s American Sonnets. The books and poems are, gratefully, everywhere. I’m on page 49 of suddenly we by Evie Shockley and next will be Best Barbarian by Roger Reeves.

LORY BEDIKIAN has been awarded the 2023 Prairie Schooner Raz-Shumaker Book Prize in Poetry and the First Prize Award in the Pablo Neruda Prize for Poetry as part of the 2022 Nimrod Literary Awards and are featured in the Fall/Winter 2022 Issue of the Nimrod International Journal. Her collection The Book of Lamenting was awarded the Philip Levine Prize for Poetry. Bedikian earned an MFA from the University of Oregon. Newer work is published in Miramar, Tin House, The Los Angeles Review, Northwest Review, on the Best American Poetry blog, and Poets.org. Her poems have also been included in the anthology Border Lines: Poems of Migration, BOULEVARD, The Adroit Journal, Literary Matters, Orion, wildness, Poetry Northwest, and featured on Pádraig Ó Tuama’s Poetry Unbound podcast, and forthcoming in Gulf Coast, Guesthouse, and the Massachusetts Review.