Virtuosity: I Know It When I See It

- By Ariel Osterweis

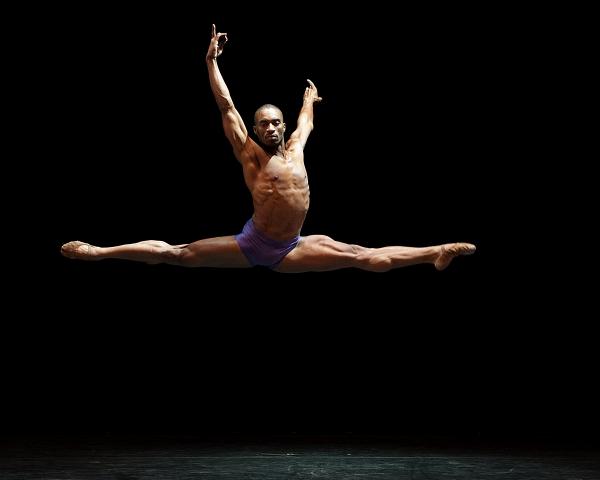

Photo: Desmond Richardson. Photo credit: Gene Schiavone. Courtesy of the photographer.

Photo: Desmond Richardson. Photo credit: Gene Schiavone. Courtesy of the photographer.

Excerpt from Body Impossible: Desmond Richardson and the Politics of Virtuosity. Forthcoming from Oxford University Press, 248 pp., April 2024.

Flung out and dispersed in the Diaspora, one has a sense of being touched by or glimpsed from this door. As if walking down the street someone touches you on the shoulder but when you look around there is no one, yet the air is oddly warm with some live presence. That touch is full of ambivalence; it is partly comforting but mostly discomforting, tortured, burning with angered, unknowable remembrance. More disturbing, it does not confine itself to remembrance; you look around you and present embraces are equally discomforting, present glimpses are equally hostile. Art, perhaps music, perhaps poetry, perhaps stories, perhaps aching constant movement—dance and speed—are the only comforts. Being in the Diaspora braces itself in virtuosity or despair. —Dionne Brand[1]

A virtuoso for the ages, Desmond Richardson (b. 1968) is a dancer renowned for delivering commanding performances over decades in contexts ranging from the stages of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT) and Ballett Frankfurt to featured appearances with Michael Jackson and Prince. He was born in Sumter, South Carolina, to a Caribbean mother from Barbados and an African American father and was raised by his mother in Queens, New York, where he would dance at house parties with his family of artists. Richardson set his dance practice in motion as a B-boy, popping and locking in Queens before attending Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts (the "Fame” school) in Manhattan and earning a contract with Alvin Ailey in the 1980s. In 1994, he co-founded Complexions Contemporary Ballet with choreographer Dwight Rhoden. Richardson is one of the most visible and admired African American dance artists and played a significant role in inaugurating what I call in this book the “virtuosic turn” of 1990s and 2000s concert dance in the US. He modeled his career after acclaimed Black dancers Alvin Ailey, Carmen de Lavallade, Arthur Mitchell, and Judith Jamison, continuing a tradition of soloism and individual artistry, and the height of his fame just preceded the popularity of ballerina Misty Copeland.[2]

It is unusual, if not unheard of, for a dancer to possess the breadth of technical expertise necessary to dance with companies as rooted in classical ballet as are American Ballet Theatre (ABT) and San Francisco Ballet (SFB) and to also have the chops to breakdance, pop and lock, and star on Broadway in Fosse numbers with equal aplomb.[3] The New York Times refers to Richardson as “one of the great virtuoso dancers of his generation.”[4] In addition, he has appeared as a guest artist on the television show So You Think You Can Dance, reaching audiences who would not otherwise have access to concert dance. Richardson’s personal style epitomizes the idea of virtuosity as—and of—versatility, allowing him to define and exceed the vast expanse that lies between the popular and the avant-garde. Especially before the ubiquity of social media, concert dancers who focused their time on proscenium stages (and not film and television) rarely attained star status. As indicated by the freedom and mobility to freelance and guest star with multiple major dance companies, he shares such status with a select group that includes the likes of Rudolf Nureyev, Mikhail Baryshnikov, and Sylvie Guillem in the 1980s and 1990s, and Copeland in the 2010s.[5] As his repertoire expanded, Richardson gained more control over his career, seamlessly traveling between commercial and concert dance settings. For aspiring dancers training in a variety of institutions, from nonprofit conservatories to for-profit studios, Richardson’s dancing has become the prototypical example of a predominant contemporary strand of the stylistic mode that is virtuosity.

Body Impossible: Desmond Richardson and the Politics of Virtuosity responds to the need for rigorous theoretical investigation of virtuosity in dance and performance studies. To that end, this book is not a biography and is, instead, a project focused on cultures and theories of performance, with Richardson’s artistry at the center of its inquiry.[6] Focusing on the decades approaching the millennium, this book brings dance into conversation with paradigms of race, gender, sexuality, and class to generate a socioculturally attentive understanding of virtuosity. Virtuosity obscures the border between popular and high art, and Richardson’s versatility epitomizes the demands on the contemporary virtuosic dance artist. I argue that discourses of virtuosity are linked to connotations of excess, and that an examination of the formal and sociocultural aspects of virtuosic performance reveals underrecognized heterogeneity in which we detect vernacular influences on high art. In doing so, I account for the constitutive relationship between disciplined perceptions of virtuosity’s excess and the disciplining of the racialized body in national and transnational contexts. In a media-driven culture devoid of systematic dance education, let alone dance education that focuses on racial and ethnic breadth and understanding, concert[7] dance audiences in the US tend to value Eurocentric aesthetics, and African American influences on ballet and contemporary dance either go undetected or are received as excessive. The paradox of audience reception is that perceptions are actively disciplined through a passive omission of non-Europeanist styles and influences by journalism and the educational system (thus critics and audiences themselves). Virtuosic modes often insist on speed, complexity, and seemingly unending climax. Virtuosic performance exposes a great deal about cultural taste: audiences are skeptical of inexhaustible movement while simultaneously expecting it of Black dancers. This ambivalence characterizes responses to virtuosity in dance emerging during the mid-twentieth century. Because virtuosity is as derogatory a designation in certain contexts as it is celebratory in others, it is important to examine the foundation and evolution of the concept’s instability.

I have selected six distinct performance contexts between the 1980s and the present through which to analyze Richardson’s contributions to dance and virtuosity. Keeping questions of identity in the foreground, I interrogate the racialized and gendered politics of dance, and the role of versatility in Richardson’s career. This book concerns itself with both the discourse of virtuosity and the mechanics of its production as a mode or quality. Richardson’s virtuosity is especially distinct in its mobilizing of multiple dance styles and techniques. Despite his overall signature style, one that privileges hybridity over singularity, Richardson knowingly emphasizes certain techniques in certain settings to respond to the call of the work in question. I place a great deal of focus on Richardson’s concert dance career, specifically on his work with the companies of AAADT, Complexions Contemporary Dance, ABT, SFB, and Ballett Frankfurt, and also look into his time at LaGuardia High School and his work with Michael Jackson. In doing so, I trace a dialogic relationship between ballet and modern dance techniques and black street dance styles such as popping and voguing. Such a study provides an opportunity to extend the scope of critical dance studies, performance studies, black studies, and gender and sexuality studies to include thorough investigations of virtuosity, race, and sexuality at the intersection of concert and popular dance cultures. After house and hip-hop dancer Jimmy “Cricket” Colter, I will adopt throughout this book the understanding that the larger category of “street dance” includes the following subcategories: club forms (house dance, punking/waacking, vogue), breaking (the first dance of hip-hop), freestyle hip-hop/hip-hop dance, funk styles (popping, locking), and dance hall. “Hip-hop” has become the umbrella term; so has “popping.” There are many forms that fall under popping (strutting, bopping, robot, waves, etc.).[8] While not inaccurate to refer to street dance as “black vernacular dance,” I will be culturally and stylistically specific when relevant.

Transcending boundaries of style, Richardson has attained a status of exception and experiences wide acceptance in the face of the exclusion of other dancers of color. We thus detect racialized cultural practices of consumption in which virtuosity cannot stand alone as such; audiences often expect of Black male dancers the fulfillment of athletic ability, charisma, and muscularity that reads as heteronormative virility. What emerges from my research is a close study of the relationship between aesthetics and politics as pertaining to queer black masculinities in dance. At the crux of this book’s exploration is the idea of the repetitive yet transmuting embodiment of the cultural: virtuosity is at once contained by and in excess of culture’s hold. Movement in its many iterations—of the body, through space, and across cultures—is central to Body Impossible.

Notes

This is a draft of the introduction that has been accepted for publication by Oxford University Press in Body Impossible: Desmond Richardson and the Politics of Virtuosity by Ariel Osterweis due for publication in April 2024.

[1] Dionne Brand, A Map to the Door of No Return (Toronto: Vintage Canada), 26.

[2] Ailey, de Lavallade, and Jamison were all important mentors throughout Richardson’s career.

[3] Richardson was nominated for a 1999 Tony Award for Outstanding Featured Actor for Fosse.

[4] Jennifer Dunning, “DANCE REVIEW: The Many Aspects of Complexions,” New York Times, August 1, 1995.

[5] Today one thinks also of Maria Kochetkova (b. 1984). All dancers mentioned here are principal ballet dancers, and the ability to earn “guest artist” status is most often bestowed upon virtuosic ballet (as opposed to modern/contemporary) dancers, largely due to the relative financial stability of major ballet companies and ensuing opportunities. Richardson’s excellence in ballet affords him increased mobility and notability.

[6] A biography, after all, would concern itself more with the poetics and psychology of the vicissitudes of life choices and the joys and anguish of everyday stops along an amply populated and narrativized journey.

[7] My statement here focuses on concert dance audiences; a different kind of argument could be made for/about, for example, social media’s dance audiences (and participants). For example, TikTok presents a different set of issues, wherein audiences and participants may be exposed to many black popular dances, but without much knowledge of their cultural foundations.

[8] “Black vernacular dance or vernacular dance are terms coming from academia; I use them if I need to, but I mainly stick to the language of the culture. That’s how I learned it, so that’s how I relate it.” Jimmy “Cricket” Colter, conversation with the author, October 2022.

ARIEL OSTERWEIS is on faculty at the California Institute of the Arts. Osterweis has worked professionally as a dancer and performer with Complexions Contemporary Ballet, Mia Michaels R.A.W., Heidi Latsky Dance, and Julie Tolentino, and as a dramaturg for John Jasperse and Narcissister.