10 Questions for Daniel Byronson

- By Franchesca Viaud

I would have liked to see myself going into the little room at the Café Boscán enraged and pistol in hand looking for his face facing some other face among the tables. He spoke wet, moldy words. I’d have stuck the barrel of the pistol to his forehead and, sublime as he ever was, he would even thank me for granting him the iron’s cool touch in the final moments of his life. Midnight sparrowhawks rose up, shaken, from the tables. Halfway through the foxtrot a shot rang out and when the lights came up they saw me, kissing the blood that ran across the shadow’s face. It tasted bittersweet and when I awoke from my dream I said so.

—from "Selections from Ballads of Sweet Jim," Volume 65, Issue 1 (Spring 2024)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you translated.

In college, was on an exchange semester in Montevideo, Uruguay, and the finals period was much longer than I was used to. I had something like six weeks without classes, and needed some kind of a project for my idle time. I translated a series of Juan Gelman poems called Carta abierta, which are twenty-five poems addressed to Gelman’s son Marcelo, who was disappeared and murdered by the Argentine military junta. I didn’t have any thought of publishing it, and I later found it had already been done [as Between Words: Juan Gelman’s Public Letter, translated by Lisa Rose Bradford]. That was the first time I translated a set of poems that all went together, and I caught the bug.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

I am inspired by Clayton Eshleman’s translations of Vallejo and W.S. Merwin’s translations of the Spanish romances (the medieval and Golden-age troubadour ballads). Both have written about how they began those projects in order to learn how to translate—if I recall correctly, Eshleman began translating Vallejo partly in order to learn Spanish, a choice that dazzles in its absurdity. Both have also written about how the first versions they produced were imperfect. Merwin writes of learning to choose which of the romances were good poems in the first place: some early versions fell flat because the source material wasn’t compelling. Meanwhile, Eshleman published revisions of his versions of Vallejo for the entirety of his career. I admire that he was not afraid to change his mind, and so to “reveal” that his earlier efforts were not infallible.

What other professions have you worked in?

My day job is in legal defense for immigrants to the United States. I have also worked as a bookseller, an elementary-school educational assistant, and a tennis coach. I teach English classes for adults on a volunteer basis.

What drew you to write a translation of this piece in particular?

What drew you to write a translation of this piece in particular?

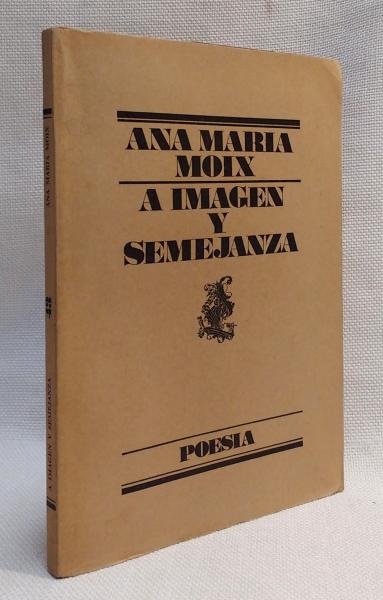

I picked up Moix’s book serendipitously, I think because it is such a beautiful object: it was published by Lumen, whose old-style paper wrappers are very appealing to me. I came back to it long afterward to translate it. I don’t remember what gave me the idea. Moix’s vision seemed, and still seems, totally unique. It is as if she is writing melodrama, but she doesn’t abuse her characters. She takes them totally seriously. I was also surprised to learn that Ballads of Sweet Jim was her only full-length work of poetry: she abandoned the form afterwards, and is remembered for her prose. So, I think I may be trying to do the poems a little bit of justice. I can’t read any new Moix poems, but I can make these ones “new” in English.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

I think the answer is every place that I have ever been.

Is there any specific music that aids you through the writing or editing process?

I do first drafts longhand, without distraction, outdoors if weather permits. While typing and revising, jazz or classical guitar works for me: for example, Christian Scott or John C. Williams.

Do you have any rituals or traditions that you do in order to write?

I’m sort of crepuscular. The first few hours of the day, I find my mind is flexible enough to read or write poetry. By noon, or even sooner, it’s too rigid. Some days I’ll get a second wind before bed. Going outdoors is fairly important, even if I go back inside to write, as one often must in Minnesota.

Who typically gets the first read of your work?

When I’m compelled by a poem, I read it aloud to a college friend by voice message. Helpfully, my friend knows enough Spanish to appreciate the phenomenon, but not enough to nitpick my versions.

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

Printmaking or music. Part of the way I stay connected to the Spanish language is by learning and playing music. Recently I’m proud of mastering “Verde,” which is an adaptation of the Lorca poem “Romance sonámubulo,” in the version released by Manzanita. I play lots of classic American folk as well.

What are you reading right now?

I recently finished the collected poems of Raymond Carver, which I recommend. I’m now reading stories by Clarice Lispector in the lovely edition by New Directions, and Time Without Keys, a volume of selected poems of Ida Vitale, translated by Sarah Pollack. I have previously read Vitale in Spanish: her poetry can be quite dense. The translations are very good and are helping me to unlock it.

DANIEL BYRONSON is a translator from Spanish and poet. He was raised in Minneapolis, MN, where he now resides. His reviews have appeared in Rain Taxi. By day, he works in immigration law.