10 Questions for Adrian Blevins

- By Franchesca Viaud

Years after it was over and he was gone, I would think of the unfortunate woman

he was living with now and engaged to marry. Poor woman with the face

so pale and flat

like a slide down a mountain rock. Poor plus-fifty bride-to-be with the voice

too whispery

and the chin too jutty. The hair too thin and white, the thighs too big, the walk

so lumbering.

—from "Quiet Part Out Loud," Volume 65, Issue 1 (Spring 2024)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you wrote.

It’s so hard to remember! I started writing at 13 or so, and wrote terribly forever. Terrible poems, terrible stories. I think I was a sentimentalist. I took myself too seriously. I wouldn’t have known a cliché if it hit me over the head with a hammer. But eventually, something new or more authentic started to click. When I was 17 I wrote a story called “In My Grandmother’s Bathroom” in this Holden Caulfield voice that I actually published in a little magazine called Virginia Country. It’s the weirdest thing ever. It’s from the point of view of this sassy girl of some sort finding her grandmother dead. I think I have always been obsessed with death. And family.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

I started writing by falling in love with all the great southern prose stylists—William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, Eudora Welty. Welty and Toni Cade Bambara had a profound impact on my sense of the importance of voice. Welty’s “Why I Live at The P.O.” and all of the stories in Bambara’s Gorilla, My Love were so very important to me. I can’t even articulate how important—how profound my love here was. I also loved Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint. It is absolutely not au courant for me to mention Philip Roth right now or that book, but I was obsessed with learning about voice, and he was so smart, so daring, and so polyphonic. I wouldn’t have known the word “polyphonic” back then, but this just means multiple voices. And he sure could layer them. And so could these other writers. And I am just getting started here—I was really an obsessive reader starting at a young age. I was a lovesick reader.

What other professions have you worked in?

I’ve been a babysitter, a waitress, and a teacher. That is truly it. I had my first child at the age of 22—I was a senior in college; it was 110% intentional—and therefore we can also say that I was a mom. I was a sister—I am a sister—and a daughter. I have been a wife at various times. Are these occupations? They’re not. But the work of my life can be understood by thinking about these relationships.

What did you want to be when you were young?

I wanted to be a hippie mom and live in the mountains of Virginia and write and just hang out and make homemade yogurt and granola and read Annie Dillard and wander around the countryside like her and know the difference between cinquefoil and dandelion, bellwort and buttercup. My dad was a funny man, and taught my sister and me to say that we wanted to be purple telephones when people asked us what we wanted to be when we grew up. We did say that, and people did laugh. But I didn’t want to be a purple telephone, really, though I did want to grow up. And so grow up (way too fast) I did.

What inspired you to write this piece?

What inspired you to write this piece?

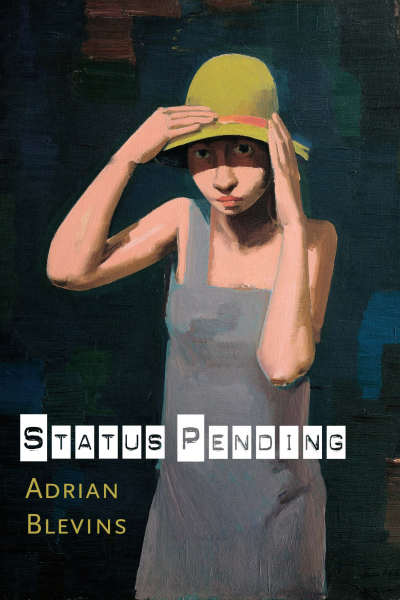

This poem tries to wrestle with a beauty problem, an idea I got many years ago from Elaine Scarry’s On Beauty and Being Just. The idea is that it is horrifying—beyond fucking horrifying—to discover that something you thought was beautiful is not. It is a humongous shock to learn that you did not know someone you were married to for more than two decades. When my ex-husband left in the dark of night when I was at the AWP (doing a panel with Diane Seuss about rural spaces being a “wrecked Eden,”), I felt like I’d been literally shot. It was so shocking that I actually had a small heart attack two weeks later, and now need a pacemaker to keep my heart rhythms steady. The shocking thing is to realize that I had been wrong for so long about who this man was. The cruelty he was capable of was really beyond my comprehension, as I would never have married him if I had understood that he was the person he turned out to be. And it is shocking to learn that you can be so dumb. The women whose husbands end up being serial murderers must feel this way. It’s like you wake up one day and some old hag from hell has drained the beauty out of your husband (to butcher that great book by the magnificent Anne Carson). This beauty thing I apply to various other figures in the whole dumb story of my recent divorce (which is taken up also in my new book Status Pending), the problem meanwhile being that I too am being ugly to point out the ugliness of others. So, there it is: the beauty problem in a nutshell.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

I’m from what we call the mountain south, so those Blue Ridge mountains are where I’m from and who I am and how I talk and what I mean and how I feel and think. I want my kids to scatter my ashes over some high ridge when I die if it wouldn’t be too much trouble. I love the rural spaces in Maine also, where I’ve been now for twenty years. All of this I take up in my third book, Appalachians Run Amok, which is meant to be a defense of rural spaces. I also joke about not liking cities all that much in that book. It’s not that I don’t like cities, though. It’s that I don’t understand them.

Is there any specific music that aids you through the writing or editing process?

No—I have to have silence to hear this hum in my head. It drives people crazy, but it’s true.

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

My father was a painter, and a great permission-giver: he really did teach us all—his kids and his students—to be their own authentic selves via the art they made. I have the visual skill of a blind stone. But I would paint if I could. Still, my love for the medium of English—and it is a medium—has sustained me for almost all my life; I don’t think I would honestly trade it in for paint.

What are you working on currently?

My fourth book of poems, Status Pending, just came out, so I am not all that far along with new work just yet to be able to name it. “The Quiet Part Out Loud” is not a Status Pending poem, though, so maybe it’s the beginning of the new thing. I’ve been tossing the words Last Blasphemies around in my head. Do you think I should work more on this beauty problem issue? I am also interested in breaking taboos. George Orwell says in review of a novel by Henry Miller, “Good [writers] are not orthodoxy sniffers, nor people who are frightened by their own unorthodoxy. Good [writers] are people who are not frightened.” People who’ve read my work would say that I have been breaking taboos since the minute I started writing, but I don’t know—this poem seems to cross new boundaries.

What are you reading right now?

I just finished Edgar Kunz’s Fixer. Great book! Kunz is a master of working outside the gutter, or whatever they call in cartooning when you let things happen off the page. In poetry and prose it’s implication, which is the opposite of tell-it-all-now-and-loudly, which is how I seem to operate. Could I write poems that broke taboos but also left a sufficient amount unsaid? Could I build more silence in? That would be fun. I will try.

ADRIAN BLEVINS'S fourth book of poems, Status Pending, is forthcoming this fall from Four Way books. She is a professor of English and Creative Writing at Colby College in Waterville, ME, where she directs the creative writing program.