What's in a Name

- By Jim Hicks

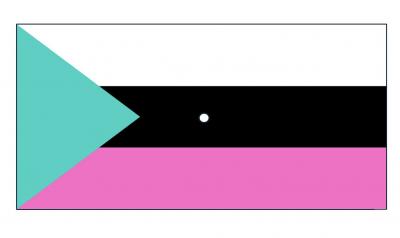

(Palestinian Flag, with bullet hole, pace Jasper Johns.)

(Palestinian Flag, with bullet hole, pace Jasper Johns.)

“Palestinians are one of the final reminders that a future without colonialism is possible.”

– Devin Atallah and Sarah Ihmoud, “A World without Palestinians”

In the time since we posted the call for our special issue, “The View from Gaza,” which will be guest-edited by Michel Moushabeck, we’ve received a number of queries, and criticism as well as support. Rather than reply individually, I thought it might be helpful to outline publicly my own reasons for supporting this project. Though I have asked for input from other editors, as I always do, I should emphasize that the ideas I express here, insightful or limited as they may be, are my own. Over my fifteen years as Executive Editor of this magazine, if there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that the opinions of our editors vary widely, and that our collective vision is strengthened by this diversity.

Our call is both concise and clear: we want to hear and amplify Palestinian voices. Also, notably, in just over three hundred words, we repeat the word “genocide” three times in describing the war on Gaza. We do know something about the history of this term: how it was coined by Raphael Lemkin, in response to Nazi violence during World War II, and how, in 1948, the United Nations General Assembly adopted, in its Genocide Convention, the definition, “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” And we are also aware that the ruling in January in favor of provisional protective measures by the International Court of Justice, regarding the genocide case brought by South Africa against Israel, is not a final verdict. We also note that, since the ICJ ruling, Israel, rather than comply with the Court’s orders, has continued its catastrophic assault.

War crimes can be obscene and massive and yet not be genocide: the killing fields of Cambodia, it was suggested to me, ought to have made this clear to everyone. However, when the entire population of a region is brought to brink of famine, the time for public discussion is over, and waiting for the criminal tribunals to conclude only aids and abets the killing. Other than Israel itself, only the US has the power to end the bloodshed now, and that is the only thing that matters. As Masha Gessen has memorably put it, “Never Again” must be a political project, not magic spell. This time, it can be stopped, and it must be.

If the stakes weren’t so high, it would be simply grotesque historical irony that Gessen, along with Judith Butler and Nancy Fraser—three of our leading public intellectuals—have been accused of antisemitism and singled out for sanctions in Germany (somewhere where you’d think someone might think twice before silencing Jewish thinkers). I would not be surprised if the Mass Review, in some quarters, comes in for similar criticism, despite the fact that it was founded and led throughout the sixties and seventies, its glory years, by a rather amazing cohort of progressive Jews, including Leonard Baskin, Lisa Unger Baskin, Jules Chametzky, Anne Halley, Sidney Kaplan, and Jerome Liebling. I feel certain that our ancestors would stand with and behind us in putting this issue together.

To some degree, I realize how hard it must be for the descendants of people slaughtered during the Holocaust to hear Israel accused of genocide. My understanding comes, in part, from a lesson I was taught during an earlier debate, after the late Archbishop Desmond Tutu had stated publicly that he considered Israel an apartheid state. (Human Rights Watch later demonstrated how Israel’s treatment of Palestinians did fit the description of apartheid, as established in international law.) This lesson was given to me by Adam Sitze, in a discussion we published back in 2014.

Here, transposed slightly from its earlier context, is what Adam had to say:

What, really, does it mean to listen to a voice we’re not prepared to hear? What does it mean to hear a word, such as for example “apartheid,” that we’re not prepared to understand—or, more to the point, that for a host of reasons we’re positively determined to misunderstand, to refuse to grasp and comprehend? […]

It’s not difficult to conjure up an answer: [some will reject] this word because it seems to be a word that stings, a word that hurts, a word that burns. It seems a word that matters primarily because of what philosophers of language would call its “performative force,” its status as a speech act, as an utterance more akin to an act than to speech. But perhaps precisely the opposite—to be able to hear, in this speech act, speech more than act—is what it means to be able to listen, to strain to hear what we don’t want to hear. To find sense and meaning in what at first seems to us a mere action, and a hurtful action at that—perhaps that’s what it means to hear the claim of someone who’s saying something we don’t want to hear, something we want to believe is not true.

That’s the first thing that I would want to say. For those who experience the word “apartheid” not only as a speech act, but more precisely as more act than speech, it burns the ears to hear Israel discussed as an apartheid state. But once we can hear the speech in this speech act, once we let the red burn of outrage in our ears subside, then we can hear in this discussion an important corollary, even a promising corollary.

If, in this earlier context, the word “apartheid” appeared as more act than speech, how much harder must it be today to hear, as we must, the word “genocide” echoing throughout this analysis, along with “apartheid.” And yet, as Sitze reminds us, “In apartheid South Africa, after all, we witnessed bitterly opposed enemies come to a negotiated settlement. We saw a new social compact and a new constitution whose appearance came as a surprise to almost all of the country’s closest observers.” Like Adam Sitze on this earlier occasion, I believe that to refuse to hear the word “genocide” in discussions of Israel today is to refuse the South African path as a possible future for Israel and Palestine. Indeed, such a refusal would belie the radical transformation of Germany itself, postwar and then again after 1989. Is it really impossible to imagine a democratic, egalitarian future for the land from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea?

In times like these one does need to state one’s position clearly, so, on a question that will inevitably be asked, I’ll echo my friend, the writer Tabish Khair: Yes, I support the right of Israel to exist, because it exists. I’ve spent a sizeable portion of the past quarter-century in Bosnia-Herzegovina, so I am certainly aware of what follows when the powers-that-be decide to eliminate countries or populations from the lands where they reside. That’s what we have to stop—never again, for anyone. On the other hand, I also agree with Thomas Suarez, who recently commented in a lecture at UMass that no state has an inherent right to exist: states earn that right only by the rights they afford to the people they serve. This lesson, I should add, the United States has never fully learned.

Even today, one still sometimes hears Israel referred to as “the only democracy in the Middle East.” Only democracy in the Middle East? As Gandhi said of Western civilization, Yes, that sounds like a good idea. We know where the opposite road, the road of racism and violence, leads: archives like Yad Vashem, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, or the USC Shoah Foundation document that reality. Yet Malcolm, Martin, and Medgar have also taught us that nonviolent revolution is also possible, and Mandela showed us the long walk to freedom.

What the world needs today is the view from Gaza.

JIM HICKS is Executive Editor of the Massachusetts Review