You Know You Can’t Help It, Who You Are

- By Sejal Shah

Jim,

I expect you would be surprised that your death affected me so much, that I spoke at two services for you, that I am writing about you now. We were friends, but we had not stayed in touch. So, it surprises me too. But you were a friend to me during a difficult time.

In one of your stories that we read in our fiction workshop, a twenty-three-year-old small-town New Hampshire boy named James Foley teaches inner-city middle school kids in Phoenix. Mr. Foley’s handwriting resembled a seventh-grade boy’s, he once attended a “Midwestern Jesuit drinking college, still keeps the same college-boy haircut [and has] no teaching skills, [loses his] temper, puts student papers in trash bags, often spills coffee on himself, and looks the wrong way at Marisela’s sister. . . .”

Self-awareness—what’s not attractive about that? You saw yourself accurately. In a fiction workshop, twenty-four years ago, I appreciated that you saw yourself as a character, and that you would say it. Your willingness to implicate yourself in the story.

In one of my stories, a narrator named Sejal refuses to learn to cook Indian food, eats too little, drinks too much, is far too often cold. In “Dicot, Monocot,” a story I wrote the same semester, the narrator ruminates on a friend she knew when she was younger, with whom she lost touch years ago. The narrator collects and classifies the leaves of flowering plants, dividing the trees into monocot and dicot. As if through naming and repetition, an incantation of sorts, she can invoke the past, finally make sense of it, and put it to rest.

We lived in Western Mass when Daniel Pearl was beheaded and during 9/11—who would have thought you would join those two events as U.S. history? When I knew you, you were interested in the world and didn’t see other people’s stories as diminishing your own. No—you traveled far, to Libya, to Syria, to cover those stories. You made it out the first time, unharmed, in 2011. You were rescued.

You wrote two thank-you notes to the same person—an initial one, and then a second when you learned about his specific, individual efforts that had helped free you. But then you went back; you couldn’t stay away from those stories and such suffering. In Syria, you were captured a second time—on Thanksgiving Day in 2012. We never saw you again. I had not seen you since I graduated, a decade earlier.

Who could anticipate that day in 2014? You, kneeling with a knife to your throat. You, in the desert in Syria. You, reading from a script. You, in an orange jumpsuit. A man with a British accent, all in black, holding a knife.

I will never watch the video; I will never forget the still. Jim. I will not remember you like that. That August, you became the first of the American hostages killed by ISIS, beheaded, broadcast to the world.

Jim, that’s not the you I remember, the one who lives on in my memory.

The you I know—that we knew—lives on at the World War II Club, Veterans of Foreign Wars, in Northampton, knocking back beers: we are in our twenties, and we laugh and laugh. There is nothing we have more of than time.

I don't need to tell you—writing workshops are odd and intimate spaces. In those small classrooms, we read and discuss each other’s work before returning drafts with a personal response, a letter to the writer. In stories, we reveal hidden histories, our interior lives, our sympathies—the ways in which we observe the world. Even in fiction, maybe especially in fiction. There are truths we can communicate in fiction that are harder to write in nonfiction, where we are forced to own up: This happened to me.

Twenty-four years ago, you and I took a fiction workshop together. This is where we officially met. I was in my third year of the program. You were a first-year. I had waited to take that workshop with that professor, because on the first day I met him, he propositioned me, put his hand on my knee, blocked the way out of the booth where we sat. But I needed to take his class, so I waited another year until I felt strong enough to sit through it. You did not know any of this, but your being in the room made it a safer space for me. It was in class that I first got to know you.

We often inhabited the same spaces. I remember your smile, your easy affability, at readings, at bars. You were so handsome, that square jaw, with an accent I could not place. I knew you had grown up in New Hampshire, taught in Arizona, gone to college in Wisconsin. I had met people from those states, and you did not sound like any of them to me. A tall white boy dressed in fleece, throwing in a bit of Spanish here and there. Strikingly good-looking, but that is not what I see when I think of you. It’s that laughter, that low voice, your wide-toothed grin, your kindness, a quiet empathy, that sometimes silliness, and warmth.

In the spring of our writing class, back in 2000, the two of us went salsa dancing at some forgettable place on Route 9. You called me up. I dressed up. It was a quasi-date that went nowhere; we were good as friends. We had a little of that first-date conversation: we talked about your brothers and your sister Katie and about teaching middle school (I had taught middle school, too). You bought me a glass of red wine, but I didn’t realize you paid until after we left; we had both put money down on the table. We laughed later. I’m sure it bothered me to have paid twice for no reason, while I would guess you were glad we had left a generous tip.

I remember your comments in class (thoughtful, but quirky), and this is how I first began to know you, through your stories, and your marginalia (also thoughtful and quirky) on my stories.

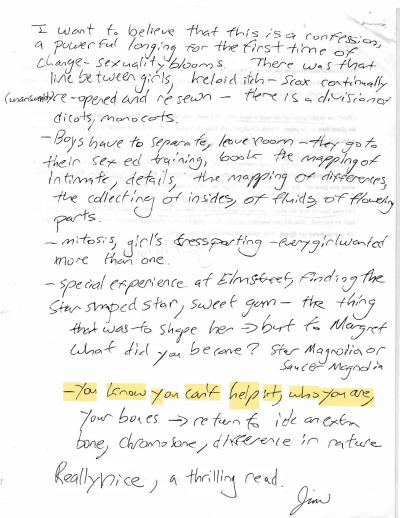

You looked up the words you didn’t know and jotted the definitions next to the words themselves, in your boyish scrawl. You wrote a definition for dicot I did not entirely know, even though I used the term in my story. Dicot < dichogamous = having both pistils and stamens, able [to] crosspollinate. You gave my stories your attention and your eye: what all writers crave. You wanted to know; you were thorough.

Fourteen years later, after I heard the news, I felt compelled to comb through boxes from years ago in my parents’ basement. I searched and found those old drafts of my workshop stories and your workshop letters to me. I showed your annotations to my ninth graders. Look, I told them, my friend Jim looked these words up. He used the dictionary!!! Or the computer. Our cell phones were not smart then. My students looked back at me blankly, not knowing what I was talking about, not understanding the urgency in my voice.

One of our professors described you at a memorial service as “golden.” Yes. I never once doubted you would return safely home. You were charming, gracious, good, and charmed.

You went back. People asked why; you had a desk job at GlobalPost. You said once in an interview that you got caught up in the adrenaline. You had given most everything away—had just what you could keep in your car, weren’t interested in possessions, settling down, a house, a stable job, what was expected of you, of us. You said that it wasn’t worth it—to put your family through that. But there was a pull—you got drawn back by the stories, the culture, the nicotine high of it, the drama of it? The suffering in it. A kind of keen empathy you had, to see beyond your personal comfort to the lives and suffering of others.

In October 2014, I attended your funeral in New Hampshire and the memorial service in Maine. I thought about the fact that you and I were the only two of the classmates I’d been friends with within our larger friendship group who had not married nor had children. We both had that restlessness, though yours took you far and I had moved back home.

It was an awkward writing workshop we were in, a mix of different voices that did not cohere into any sort of community. It was more than awkward for me; it was toxic. But being around you put me at ease. I always felt safe around you. Everyone sat a bit in awe of our professor. I had to fend off his advances. You spoke carefully in class. You were a first-year, and I could see that you thought I was older, more senior. That didn’t last long. Bars and parties equalized everything. Sharing writing with other people in a workshop can also be unsafe: you need some support to do it. It was a pivotal writing workshop. It was pivotal in my life. Your being there was pivotal in my life. It was a sinister set-up; these things so often are for women, but I was young and didn’t know how to handle it. You made an unsafe space more tolerable, bearable.

Clare Morgana Gillis, the journalist who was captured and held in Libya with you, wrote after your death: “Identity, we are told, is a shifting construct—we act one way with family, another at work, differently with lovers and friends and strangers. Jim’s unique characteristic is that every story his friends tell makes the rest of us laugh and shake our heads about how we all knew exactly the same man.”

I keep so much from my past: I still have my grandparents’ passports, the mimeographed program from my first-grade play, the leaf project from sixth grade on which I based “Dicot, Monocot.” I am relieved to find your comments on those workshop drafts, to see your handwriting, how you sign your name. I study what you have written, two pages long, on my not-even-three-page story and reread a sentence, left after you signed your name:

I like the pathos you lay out there, your writing is risky, barbs underneath a fleecy texture.

I linger over your words. I am pleased you call my writing risky. If you are lucky, you get one or two writers who see you and what you are trying to do. Who see the possibility in your work. Knowing you did this for me—made me lucky.

In the fall after our workshop semester, I see you at all the usual parties and readings and bars in Amherst and Northampton. One night, with two friends, we skip from a reading to a bar to another bar. “Let’s go!” we say. And we go. We take off and drive down 91 to Springfield, we find ourselves a place and we dance hard.

We end up at the Mardi Gras, which our professor had written about. I had never ventured into a strip club before. The thumping music, the sadness, the bright lights. The strippers and the viewers, the spectacle and the transactions, the voyeurism—it all disturbed and intrigued me. I wouldn’t have gone in, had I not been with you. Most of us had our groups, our circles, the petty factions, but you belonged to everyone, slipped from one to another scene, a party thrown by international students in another department, welcome everywhere.

Maybe I told myself we were participant-observers: we were ethnographers. As a woman, I felt implicated even by entering the club. My face flamed; I tried to act unflustered. I wanted to see more than our circumscribed, liberal, predictably PC college town. And then we are sliding into another bar, laughing, another beer and it’s 2:00 a.m. We could have kept going—Hartford, New Haven, then Manhattan, Queens, Brooklyn. Why not? That night, we could have traveled anywhere, anything was possible: the night grew, expanded. We could drive anywhere; we could do anything. There was always that magic with you.

As writers, we want to see things: to record what is out there in the world, in all the chambers of the human heart. That night, we crossed over into another country far from where I had spent my time: everyone under thirty, handsome with youth, few rings on any fingers, no thought of what next. Unlike the rest of us—losing our hair, nerve, and youth—in the years before 2014, you will grow even more handsome with age, your features sharpening, your eyes lined.

We graduated. You and I both turned our energies toward nonfiction. Your writing launched you far outside yourself, working with single mothers, then to journalism school, then to Libya and Syria. I still trace and excavate my smaller circumference, circling and circling back, but my world includes you.

Jim, after I hear the news, in the only picture I can find, you are in Food for Thought Books in Amherst. That bookstore is gone now, too. It was the spring of 2001. I had organized a Writers of Color Reading to raise money for earthquake relief in India. I was mad that there were so few writers of color in our program and wanted a space for writers of color to hear each other’s work.

You are introducing our friend, Yago, before he reads his poems. You are not a writer of color, and so I am taken aback, surprised, when I unearth the photo with you up there at the podium. What were you doing there? Then I remembered. Of course you would have been there, not sitting back in the audience, helping out, introducing Yago, showing up for me and our friends and cheering us on, present for the reading and stories and poems.

I want to tell you how much it meant to me that you spoke at that reading and came to my final MFA reading. I remember my hands shook, icy, at both. I wore my mother’s earrings and an ice blue shirt, a black wool shawl across my shoulders for warmth. Your kind eyes in the audience bolstered me, calmed me, gave me faith that it would all go all right, that everything would be fine. I’m not surprised that you wrote two thank-you notes. I’m sure they were beautifully written. Your writing. It’s one of the ways in which you live on.

I look back at your workshop comments, wanting more of your words. Here is more of what you wrote:

I want to believe that this is a confession, a powerful longing for the first time of change—sexuality blooms.

Question who is assumed audience—white America?

Why is it important to question the audience / form of story?

And then, toward the end of one of your workshop letters, you wrote: What did you become? You know you can’t help it, who you are, your bones . . . Then a final sentence, Really nice, a thrilling read. Jim

You know you can’t help it, who you are. Jim, you are someone who did not turn away. You are someone who looked closely, who studied my stories, who studied all the stories you read. I am someone who has spent ten years writing you this letter, and still, I don’t know how to end it, Jim. Even your parents said they thought you had nine lives.

I am writing to you as though it will bring you back. I was sure you would come back. These words are my conjuring. Your words are one way back.

Sejal

SEJAL SHAH is the author of How to Make Your Mother Cry: fictions (West Virginia University Press, 2024), a short story collection dedicated to James Foley. The full text of "Dicot, Monocot" and more of Jim's workshop comments are included in her book. For more information about How to Make Your Mother Cry, visit sejal-shah.com. For more information about Jim's story and legacy, visit jamesfoleyfoundation.org.