The Songwriter as Poet. A Conversation with Phil Elverum

(Part One)

- By Jon Hoel, with Phil Elverum

Phil Elverum, photo by Katy Hancock

Phil Elverum, photo by Katy Hancock

Poems are songs, songs are poems. This dictum may infuriate anyone who has ever penned an editorial on Leonard Cohen’s songs or anyone who was irate when the Nobel committee declared Bob Dylan was literature. Those familiar with the history of songwriting, however, might be inclined to agree with such an equation, knowing their shared origin points.

Anyone presented with a songwriter such as Phil Elverum—who under the moniker Mount Eerie (and The Microphones before that), has been making some of the best music of the last few decades—would be compelled to do so. Elverum’s music is intensely emotional music, recognizable by its intricate, thoughtful instrumentation, wonderfully orthodox punk production style, and some of the best lyrics of any songwriter of his generation.

Elverum’s propensity to elevate the natural world in his work recalls not just great songwriters, but great American ecopoets too: Robinson Jeffers, Alice Notley, some Gwendolyn Brooks, and centrally, Joanne Kyger.

Night Palace is both an album and book of poems, his first new work in five years. The writing distinguishes itself concretely from Elverum’s previous work, which attempted a frenzied cataloguing of human life and experience—grandiose, plentiful. This new work is generous as well, but ambitious in a different way: “I take everything, I’ve already figured out with me wherever I go,” writes Elverum. “Mind like a moth-eaten blanket / Wind whistling through the holes.”

In late September, I spoke with Elverum about his new work, his career, and craft.

Jon Hoel: Phil, you’ve released many albums, over thirty years, but to my knowledge no prior poetry publications. With this new project, what compelled you to release a chapbook of poems?

Phil Elverum: When I was teenager, lyrics came at the end because I was focused on building the songs and the recording experimentation. But I knew it had to have words to make it a real song, so I would come up with some personal stuff… I did care; it wasn’t meaningless, made-up language. But at a certain point my focus shifted toward what I was communicating and caring about that in a beautiful way.

But I have never thought of songs and poems as different things. I don’t know if that’s widely accepted or controversial, but that’s my belief. That there isn’t a difference, that they are the descendants of the same ancestor. My idea to make a book version of these words didn’t seem like a weird thing to do. I felt proud of the songs and wanted them to be focused on in a deliberate lyrical way. That’s one of the reasons.

There were other books I was inspired by, other zines and small press poetry I wanted to participate in. Will Oldham made a beautiful book of his more collected songs that was letter-pressed fifteen years ago. I loved that book and dreamed of having something like that.

Hoel: In the press release, you said that they were poems first?

Elverum: There is no boundary: they’re poem-songs, song-poems—poems that get song. In the history of humanity, all this comes from people gathering around the fire and communicating, connecting with the eternal through dance, poetry, song. It all grows from the same communal exchange. The idea that printed poems on the page are the true version is so short-sighted.

Hoel: For Night Palace I had the privilege of having those songs you had already released (“I Walk” & “Broom”), so I could listen to them. Then, reading the poems in the book, I tried to imagine how they might sound, and if it would make a difference, what melodies might accompany them. It was a very different experience from encountering a piece of music with everything immediately present. Like buying a CD and reading the lyrics before you hear the songs.

Elverum: That was my initial idea: I wanted to have the book come out first without mentioning the album, to let people experience it in that mode, with the phantom music of how the songs might sound in their own minds as they read. Then later, when the album comes out, they find they had imagined it totally different. The clash of preconception and reality is inherently interesting. I’ve had that experience, reading other people’s lyrics or reading a poem and then hearing a recording of the poet reading or singing it. It’s always different than I imagined it. I love that feeling.

Or cases where you read the lyrics and then listen to the album, and you see what’s written is different than what is sung… Sometimes it’s an error, or maybe they changed something in the studio, or whatever. I love that triangulation of a third meaning, where those two converge. It opens the whole thing up in an interesting way.

Hoel: Before this project, your most recent release was The Microphones in 2020, which you described as more of an audiobook than an album. I liked that description. When I relisten to that album, it’s very Whitmanian. It’s very maximal, it’s full-blown, every detail is there. These new poems, though, are very Dickinsonian. They’re little emotional punctures: they achieve similar heights, but in a very different way. I’m curious how you see these poems and songs interacting with your more recent work?

Elverum: I wrote in this Dickinsonian mode as a response to that last work—one huge, long song about my own autobiographical details. I tried to go to the polar opposite end of the spectrum, to do micro-gestures that got at something beyond me. Where “Phil”—this person writing this thing—is not important. Even though I’m the eyes and ears perceiving, I didn’t want to center my own identity.

I have a wishy-washy relationship with the role of autobiography and identity. I want to erase myself in it; I also am too in it to erase myself. I need to write from what I know, which is my experience as a human being. I’m not going to write fictional songs about made-up characters like some people do—country songs about some guy who goes to jail or whatever. That’s a different mode, not what I’m doing. Inevitably, my experience on earth, as Phil, is going to be central. But with this batch of poems, I also wanted to transcend that, to use it more as a launching pad.

Hoel: At least in literature, it seems like that mode is changing. In the poetry I grew up with, there was a strict notion of the speaker of the poem, the clear distinction of the lyrical I, whereas the last few years it’s different. I lived in New York City from 2017 to 2019, right when autofiction was getting really big and—

Elverum: Were you at the Karl Ove Knausgaard event in 2019?

Hoel: Yeah! For the last My Struggle book?

Elverum: I was there too. Yeah, I read all those books, and in those years they affected my writing too. And I’m glad they did, but this time I wanted to try something a little different.

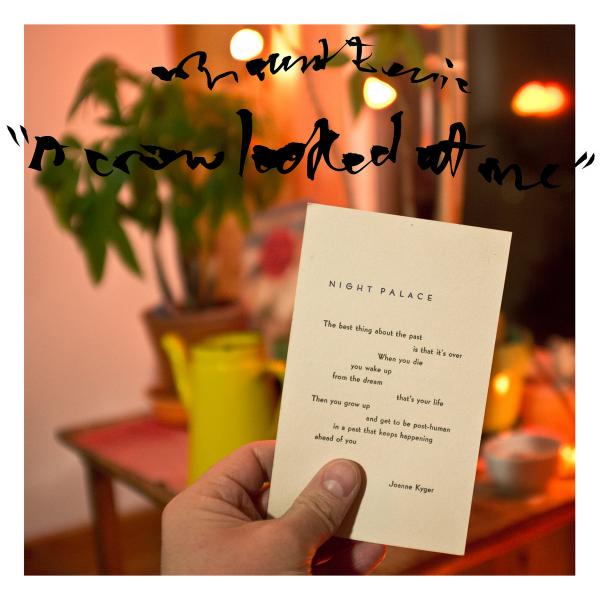

Hoel: Night Palace is named after the Joanne Kyger poem, which is one of her later poems. I knew a little of her poetry from the 1960s, but wasn’t very versed in her later work until your album came out, with that poem on the front. How did you encounter Kyger’s poetry?

Elverum: That poem was on the cover of my album A Crow Looked at Me, for very personal reasons. My wife who died, Geneviève, had a postcard with that poem letter-pressed on it tacked to the wall in her studio. I don’t even know where she got it. She was pen-pals with Joanne, she wrote to her… They were even working on a long-form zine together. It was going to be called Old People (Joanne hated the name). Geneviève had the idea of publishing an interview zine, focusing on older working artists that were still engaged in craft. We drove down to Bolinas and saw Joanne the last few years of her life.

Anyway, I was cleaning out Geneviève’s studio after she died, some months after, and that poem was on the wall. It struck me as being relevant to what was happening. Life and death, posterity, present and the past. I took a picture and used it as the album cover.

Years later, I realized it: Oh, weird, that album has this other title on the cover. It has this title, Night Palace on it, as a second title. Maybe I need to make an album called Night Palace to use up that seed that has been planted.

It’s not even about that poem resonating beyond that one record, it’s those words, “Night Palace,” they’re so resonant and powerful. There’s a lot to be explored there. That’s the zone I’ve been in the last few years. I’m not exactly sure what this is, this “Night Palace” thing—or this like “Mount Eerie” thing. These different, resonant words that have a feeling; it’s distinct to me but isn’t easily articulated. That’s my art process, trying to articulate this thing that feels big and important to me.

But you asked how I got into Joanne Kyger! I’m into her scene of poets. Late Beats, the Californian, back-to-the-land poets: Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, Lew Welch. The countercultural movement of the 60’s and 70’s, and the Pacific Northwest contingent. I remember being a kid and seeing these older poets around and knowing this cool thing was happening. It does feel personal to me. In a way, it’s part of my lineage.

Hoel: I grew up on the Beats because my parents were of that generation. Lots of Kerouac, Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti… Diane Di Prima. But I didn’t really come to Kyger until years later. I feel like that’s true for many people. She’s not celebrated as she should be. If you go to the Beat section of the bookstore, you don’t see her titles there.

Elverum: I don’t think she was working it very much; she was relatively happy just to peace out to Bolinas and write poems. I don’t know if she had frustration about her reception.

PHIL ELVERUM is a songwriter, poet, and artist from Anacortes, Washington. He releases music under the moniker Mount Eerie, and publishes books, albums, artwork, and more with his label P.W. Elverum & Sun ltd. His new album and book of poems Night Palace is out November 1st.

JON HOEL is a New England poet and critic. He is the author of a monograph on Andrei Tarkovsky's film Stalker with Liverpool University press and has published essays, poems, and interviews with Black Lawrence Press, Joyzine, Lumina, and elsewhere. He is a graduate student at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.