For They Become the River

- By Maria Nazos

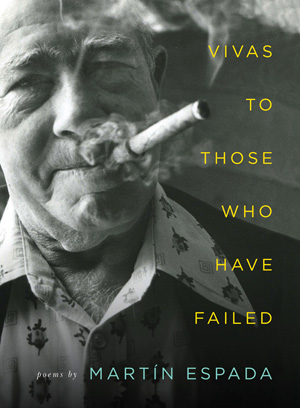

Martìn Espada’s newest poetry collection entitled Vivas to Those Who Have Failed presents a series of poems that speak to hope and despair, of a world where bullets melt into bells, and of a future in which poets provide spiritual clarity.

More concretely, the collection borrows from the elegy and ode, but never fully surrenders to either form, as the poems tread a bittersweet line between grief and hope. Vivas to Those Who Have Failed is spoken by a compassionate and unflinching narrator, delivered by a poet whose athletic execution of the sonnet, ghazal, and monostich—occasionally presented with Espada’s unmistakable repetition—is infused with social awareness.

The book begins with a cycle of sonnets “Vivas to Those Who Have Failed: The Paterson Silk Strike, 1913” which pay homage to one of the largest strikes in United States history, involving more than 25,000 mainly immigrant workers. The poem also references the strikers’ descendants, some of whom went on to become poets themselves. In the fifth section of the sonnet series, the speaker describes the violence and struggle in a particularly intense strike scene:

“…Twenty years after the weavers

and dyers’ helpers returned hollow-eyed to the loom and the steam,

Mazziotti led the other silk mill workers marching down the avenue

in Paterson, singing the old union songs for five cents more an hour.”

Throughout the collection, Espada gives a nod to poet friends and mentors who are both living and gone. In this section of the sonnets, the narrator depicts not only the bravery and carnage behind the strike, but also describes the lineage of poet Maria Mazziotti, remembering her father: “Mazziotti’s son would become a doctor, his daughter a poet./ Vivas to those who have failed: for they become the river.”

Finding the success even amid failures is one of the book’s major themes, and with good reason: Espada celebrates those who have fought for a cause, whether it is life, freedom, or both, and does reverence to his subjects by portraying their humanity and refusal to give up, no matter the outcome.

“Here I am” provides a moving tribute to the late Portuguese-American poet Josè “Joe” Gouveia. Espada evokes a poet who despite his battle with cancer “will live forever” through his presence, energy, and words. Espada uses simile to recall a friend who bursts into a gathering of his fellow poets: “sleeve buttoned to hide the bandage on his arm where the IV pumped chemo/ through his body a few hours ago.” Gouveia is mythologized with long Whitman-like lines to describe the dynamic poet’s determination to survive and thrive in the midst of his struggle:

“The nurse swabbed the puncture and told him

he could go, and JoeGo would go, gunning his red van from the Cape

to Boston, striding past the cops who guarded the hallways of the grand

convention center, as if to say Here I am:”

The speaker does not collapse into mourning, but remains convinced that even in light of his impending illness, regardless of his fate, Gouveia’s memory continues to make a painful world more hopeful and truthful. Throughout the collection, loss is a bittersweet entity; friends like Gouveia are not only mourned, but also celebrated, so that their memories remain immortal through not only their own words, but through those of surviving friends such as Espada.

As the collection continues to unfold, recent social travesties are depicted, including the Sandy Hook school shooting. The poet portrays this senseless tragedy with a sense of hope and integrity. With its sonorous repetition, “Heal the Cracks in the Bell of the World” is an incantatory call to higher consciousness rather than a call-to-arms:

“Now the bells speak with their tongues of bronze.

Now the bells open their mouths of bronze to say:

Listen to the bells a world away. Listen to the bell in the ruins

of a city where children gathered copper shells like beach glass…”

Espada’s striking use of simile, anaphora, and cataloguing are again reminiscent of Whitman—whose quotes appear in some epigraphs of the poems—and allow Espada to inhabit a multi-textured voice that contains grief, empathy, and resoluteness, often all at once.

The heart-wrenching poem “Ghazal for a Tall Boy from New Hampshire” is dedicated to Jim Foley, a journalist who was mercilessly decapitated on video by ISIS. Foley was a former student and friend of Espada’s in the University of Massachusetts-Amherst’s MFA program. The poet eulogizes Foley as a compassionate, purposeful, and a socially active man. In opposition to the sensationalization of Foley’s murder by some of the media, Espada chooses instead to gracefully and accurately exalt and lament his friend’s life, death, and vibrant memory as a hero and social activist by incorporating elements of mourning and healing to seamlessly inhabit the ghazal’s form:

“We know his words turn to rain in the rain forest of the poem.

We cannot say what words are his, even though we knew him.

His face on the front page sold the newspapers in the checkout line.

His executioners and his president spoke of him as if they knew him.”

Throughout Vivas, the speaker champions those such as Foley who have self-sacrificed, sometimes with little or no recognition, along with immortalizing those who refuse to die, but instead will live again through poetry, thus refusing to go either unknown or forgotten.

Poems such as “The Discovery of Archaeopteryx” describe a young man’s urban upbringing. Having spent his formative years in Brooklyn, the speaker visits Puerto Rico, from where his family emigrated, to confront a chicken for the first time. As the speaker describes the rooster, it takes on reptilian-like proportions as he recalls: “Here was Archaeopteryx, the feathered reptile, the dinosaur bird, / the fossil made flesh, risen screeching from the rock.” Espada uses humor, irony, and poeticism, which suddenly become grim as the speaker recounts his own father’s shock after beholding his first cockfight: “As a boy, my father learned about roosters. He saw my grandfather/ guide the bird into the pit, the wagers change hands, the gallos de pelea/whirl and slash the eyes till a blinded rooster bled into the sand.”

“The Goddamned Crucifix” provides a moving account of the speaker’s father, who appears to be on his deathbed (“his ribs spread and his chest sank/with every rasping breath. He was skinny as a rubber chicken…”), but who miraculously lives. The speaker/son removes the crucifix from his ailing father’s sight after he is told: “Get that goddamned crucifix away from me.” Just when the poem seems to be veering towards the elegy, the voice turns and celebrates the father’s strength, spirit, and resolve, while reflecting upon life’s occasional cruelties and generosities.

In a passionate collection that is socially conscious and personal, ecstatic and elegiac all at once, Martìn Espada’s collection of poems Vivas to Those Who Have Failed should be read again and again, silently and aloud, in sadness and celebration of those who have fought throughout history and refuse to be forgotten.

Maria Nazos is a poet and author of A Hymn That Meanders (2011, Wising Up Press) and the chapbook “Still Life” (2016 Dancing Girl Press).