Conversations with Susan Bernofsky, Part 3

- By Ryan Mihaly and Susan Bernofsky

The conclusion of a conversation with translator Susan Bernofsky. Read Part One here, and Part Two here.

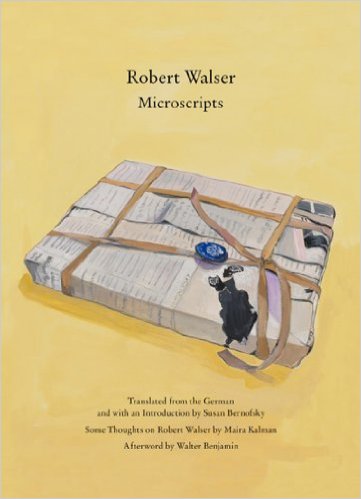

Ryan Mihaly: The Metamorphosis and Robert Walser’s Microscripts both deal with these cramped spaces – Microscripts being these texts written on the back of business cards, newspapers, pamphlets, and so on. And both Walser and Kafka write in this old, highly formal style, which comes off as very comical in English.

Susan Bernofsky: Both Kafka and Walser use bureaucratic language to comic effect.

Ryan Mihaly: Were they funny in their time, too?

Susan Bernofsky: Yes, but not everyone thought they were funny.

But think about Kafka. He didn’t have a huge reception in his lifetime. Most of his reception happened just after World War II. At that point people saw the tragic Kafka (died young of tuberculosis; story of a guy becoming a beetle; the Holocaust) and I think people didn’t figure out that he was funny for quite some time.

Walser just didn’t have that many readers during this lifetime, so it’s not as if everyone was busy talking about whether he was funny or not. Except Kafka! Kafka read and loved Walser. Max Brod describes Kafka rolling on the floor with laughter while reading Walser aloud to friends.

Both of them have humorous bureaucratic language in common, but they use it differently. Kafka uses bureaucratic language pretty straight up, and the humor comes from the contrast between what’s actually happening in the story – man becomes beetle – and the formality of the discourse. Walser exaggerates the bureaucracy and layers extra clauses and phrases on top of each other until you have these completely baroque, curly-cue, fractal-like sentences, and that’s comical because he’s challenging you to follow him.

Ryan Mihaly: The Microscripts took twelve years to transcribe from the original papers. Did you translate them from Kurrent, the antiquated German shorthand?

Susan Bernofsky: I translated the transcriptions only. Kurrent is the same as our word “cursive.” It’s just describing this form of handwriting, which was usually written full-size. German handwriting changed radically in the early 20th century, so nobody now uses this old form of handwriting.

But that wasn’t the main transcription issue. Not only was Walser writing in this older handwriting, he was writing it one to two millimeters tall. His handwriting was radically shrunken-down and almost completely illegible. Even the transcribers say they never got to the point where they could just sit down and read it, ever. One of the transcribers was describing to me how he worked. He said you can’t read the words but you can guess what they mean and then check your hypothesis. So, it takes a lot of knowledge of Walser’s work in general to guess what the next word might be.

Ryan Mihaly: New Directions also recently published The Gorgeous Nothings, a book of poems that Emily Dickinson wrote on the back of envelopes and other papers. Do you think books like The Gorgeous Nothings and The Microscripts have influenced the current trend of short-short forms and microfiction?

Susan Bernofsky: I think it’s the opposite – since miniature writing is currently popular, people have been so receptive to a writer like Walser and other short form writers. People who are reading him might be inspired to do more short form writing, but I think it’s the general interest in the short form right now that has made the reading public so receptive to him.

Ryan Mihaly: When translating, do you work on more than one author at a time?

Susan Bernofsky: No, never. Although sometimes I can be working on a book and I’ll get an urgent request to do fifteen pages, like a sample translation. I can interrupt for something short, but I never do full works at the same time. It’s one voice at a time, for me.

Ryan Mihaly: Jenny Erpenbeck’s Visitation left me feeling a bit tormented. It’s so haunting. And with Yoko Tawada’s stories, there’s always a sense of being completely lost. When you’re translating, how much do these novels get under your skin?

Susan Bernofsky: I think the books get under your skin more when you’re reading them. Because as the translator, you’re spending so much time grappling with problems that letting yourself be affected by the book would get in the way. You’re all nuts and bolts, nuts and bolts.

Siddhartha was the exception. And that’s because I read and fell madly in love with that book when I was fourteen. It’s a book that I probably would not have particularly responded to as an adult. It’s kind of a book for kids. But because I had had this primal experience with the book as a kid, I was literally weeping while I was translating it. I was like, “This is so sad!”

Ryan Mihaly: [Laughs] That’s one I haven’t gotten into yet, but maybe it’s too late.

Susan Bernofsky: You might be too old for it. But it’s a beautiful book; it’s just a little simplistic. But the simplicity is part of its thing.

Ryan Mihaly: You talked earlier about having a good book design and wanting a beautiful object to hold. The covers for your books are beautiful.

Susan Bernofsky: I’ve been so lucky. I’ve had no influence whatsoever over any of the covers. Lucky me, I have publishers that make beautiful books.

Ryan Mihaly: Do you think good design is going to help translated books become more popular in the States?

Susan Bernofsky: Yes! Good design will make people pick up a book and look at it, and be interested in it. I think design is crucial. The design that Jamie Keenan did for The Metamorphosis, the sort of gothic, creepy design – that forms part of your reading experience. It’s a commentary and I think it enhances the book as a whole. The cover is an interpretation.

Ryan Mihaly: There’s been a recent boom of really great designers working on books.

Susan Bernofsky: Yeah. Peter Mendelsund’s books...

Ryan Mihaly: They’re stunning!

Susan Bernofsky: He’s brilliant. The amount of thought that goes into every one of his covers is completely phenomenal.

Ryan Mihaly: Music plays a role in the work of all the authors we’ve talked about. And I think it’s fascinating that Yoko Tawada and Jenny Erpenbeck both have careers in music.

Susan Bernofsky: And they’re both great performers. If Yoko Tawada gives a reading, it’s a performance. At NYU I saw her perform a short story in three languages. It was the first one of hers that I had ever read, in the mid-90s, called “Canned Foreign.” It was also the first thing I ever translated by her – I had seen it randomly in a magazine, loved it, and translated it. In fact, that’s how I met her. I translated her story and sent it to the publisher asking them to forward it to the author. I was in my 20s; I was really a young translator with no credentials. She wrote back and asked me to translate another. That was our beginning of our working together.

She performed that story at NYU. She showed up in one white glove like Michael Jackson. She was reading the story in Japanese, and at one point she started reading her fingers because she had written some of the story on her hand. Then she turned the glove inside out – some other part of the story was written on the inside of the glove. Then she held up this picture of a Japanese woman over her face and read from the back of the picture. She’s very conscious of affect, and text is part of that. She talks about wanting her translators to put a lot into the translation, to change things and to find ways to enliven it, because she sees her work as open.

And I think that’s true – Erpenbeck, Walser, and Kafka, they’re all very tightly woven. Whereas Tawada writes a loose weave and leaves a lot of space for writing in between the lines and reinterpreting. The end of her short story “Where Europe Begins” is like alphabet soup. She spells out words letter by letter, and of course when you’re translating, you have different letters to work with. The word “Moscow” is spelled differently in English than in German, so it’s clear, the translator has to come up with different key words to end that story. She finds that to be an interesting addition to the work.

Ryan Mihaly: Lastly, what translations are you working on now?

Susan Bernofsky: I’m working on Tawada’s polar bear novel Etudes in Snow for New Directions.

Susan Bernofsky is the translator of, most recently, Looking at Pictures by Robert Walser (New Directions, 2015; co-translated by Lydia Davis and Christopher Middleton). Other translations include Kafka’s The Metamorphosis (W. W. Norton, 2014), Jenny Erpenbeck’s The End of Days (New Directions, 2014), Robert Walser’s The Microscripts (New Directions/Christine Burgin, 2012), and Yoko Tawada’s The Naked Eye (New Directions, 2009).

Ryan Mihaly is a writer, musician, and artist working in Western Massachusetts. He is the Interview Features Editor for Asymptote, and a contributor to Biblioklept.