Listening to Mary

- By Jim Hicks

Early on, in the 1985 film that arguably inaugurated Jean-Luc Godard's late-period work, we watch, for much longer than we expect to, a single person on a crowded sidewalk. Our view, or that of the camera, is from a nearby rooftop—surveillance in an etymological sense. At a certain point as I recall, the voiceover comments: “If you look at anyone closely enough, or long enough, you'll be more or less certain that the person under observation is insane.” (When I first saw this film, I myself was living in Paris, and remember thinking, “Anyone? Or do they have to be French?”) In a documentary film by Wim Wenders a few years earlier—a sequence of monologues by various famous directors at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival—Godard comments that any film that lasts for more than a minute has to start telling the truth. Why, he asks, do you think ads are so short?

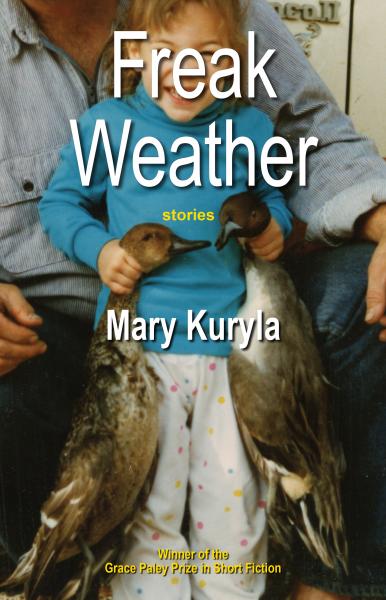

Though it will take a minute or two more to get there, soon you’ll be listening to Mary Kuryla read from her Freak Weather, the story collection that won the 2017 AWP Grace Paley Prize for short fiction. It does make sense, obvious sense, to begin an introduction of this writer and these stories with a reference to film, since Mary is herself a filmmaker and several of the stories in this collection have also become films—before spiraling back and returning to the page. I could also have also begun in reference to the stage, since the energy and bravado of Mary's characters do frequently remind one of the theater of Sam Shepard, especially the battle between Hoss and Crow in The Tooth of Crime, though the razor sex and violence of Fool for Love is in these pages, too. As you know, that one also became a film, by Robert Altman, recursively starring Sam Shepard himself.

Given the lives on the margins, the sex, the drugs, and the prison time in these pages, Denis Johnson's Jesus’ Son is another obvious analogue, particularly since, like Johnson, Kuryla's stories follow people on the move, even if they may be going nowhere, and even when they take readers out of their comfort zone. Which is, of course, the point, or at least part of it—though Mary's attitude towards her menagerie of characters is anything but freak show. In a lecture, Gilles Deleuze once commented that no one could possibly take offense at the explicit sex in Proust, because Proust looked at sexuality like a botanist looks at flowers. And with flowers, of course, it's all about display.

More than plants, though, the animals may give you pause in these stories. As in Michael Moore's first, groundbreaking film, when rabbits appear in Mary's fiction, they inhabit the most uncomfortable semiotic space imaginable: “Pets or Meat.” No, you think, no, you can't do that, those words, you can't yoke them together. Moore's modest proposal was of course a metaphor for working-class lives where there is no work; when a rabbit gets skinned in Kuryla's story, we're not far off, though it's family, not state, violence under the knife.

So, what have I left out? In a word, language. As an editor, I can guess at the back story behind many, even most, of these stories. I can imagine the baffled silence, the chain-migration of rejections, as well as the well-intentioned edits and corrected syntax that preceded their appearance here in print. If there's a word for what Mary's after, I think it was coined by Viktor Sklovsky, and that word is ostranenie. The trouble with defamiliarization, though, is that the mainstream of publishers wants to publish what has already been read, not what has yet to be written. Occasionally, of course, if you persist, if you resist, if you simply continue to exist, you do slip something by.

Did you hear what else I left out? In a word, feminism. If I did this intro right, you will not have yet noticed that, in order to introduce and lend authority to Mary's work, I've just alluded to four male filmmakers, three male writers, and two male critics. In short, to salute this woman who writes about women, who won a prize named for a woman, in a contest judged by a woman, and who has now been published by a press headed by a woman, I've inducted her into an old-boys club. All that stuff about comfort zones, about defamiliarization, well, maybe that's really not the point. It is certainly not the whole point. Because when Mary Kuryla's female protagonists persist, resist, and simply continue to exist, you can't help following them, which is the point.

The great achievement of Grace Paley was, we know, to get people and voices on the page that we had never heard before, and that we would never again forget. Nothing could be more political than that. And—in 2017, the year of #MeToo and #Time’sUp—nothing could be more appropriate than to have awarded the AWP Grace Paley Prize in Short Fiction to Mary Kuryla. Having said that, well, it's time for me to shut the fuck up, and for you all to welcome Mary to the stage.

Jim hicks is the Executive Editor of the Massachusetts Review.