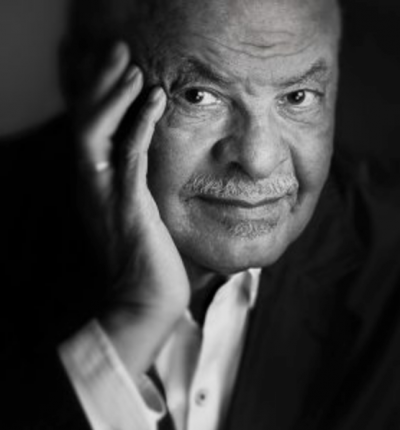

A Friend, Guide, and Comrade: On the Passing of P. Sterling Stuckey (b. March 2,1932, d. August 15, 2018)

- By John Bracey

I first met Sterling Stuckey in Chicago fifty-five years ago. In the spring of 1963, Sterling and a group of high school teachers—graduate students at the University of Chicago—were in the process of forming a community-based organization to address the “lack of a proper consideration of the role of the Negro in American history.” Sterling at the time, along with Don Sykes and Thomas Higginbotham, was teaching history at Wendell Phillips High School, located in a predominantly Black neighborhood on the Southside. I was among a group of undergraduates at Roosevelt University undertaking a similar project, who were asked by Sterling to join the newly named Amistad Society. I participated in the workshops and panel discussions, introduced guest speakers and served a stint as secretary.

The overtly political work of the Amistad Society included raising funds to help support an ongoing civil rights effort in Fayette County, in Sterling’s home state of Tennessee. A number of Black folk were living in a “tent city,” having been evicted from their homes for registering to vote. We also undertook a similar project to provide relief support for the people of Angola in their struggle against colonial domination by the Portuguese. That initiative involved close collaboration with the Pan-African Students Organization in the Americas, whose leaders, Chimere Ikoku and Obi Wali, were well known to Sterling. In May of 1963, both men participated in a series of lectures entitled “Heritage: the African Background.” My participation in the Amistad Society gradually diminished as, by the summer of 1963, I had become more active in local civil rights struggles.

During my years at Roosevelt University, I continued my study of the African and African American experience with such figures as St. Clair Drake, Lorenzo Dow Turner, and August Meier. I remained active in politics both on campus and in the Chicago Black and left communities. I saw Sterling rather sparingly during those two years, until the fall of 1966, when we found ourselves together as entering doctoral students in history at Northwestern University.

Sterling had earned a master’s degree in history at Northwestern, and was much more acclimated to the town of Evanston and to Northwestern than I and the host of Black first-year students who arrived that same fall. Northwestern, located on Lake Michigan, had its own private beach and was generally known for its social life, centered around Greek organizations—the “Sweet Heart of Sigma Chi” and all that. Except for the fact that they had a great African Studies library, serving the program founded by Melville Herskovits (who had passed on), the general academic status of the various schools and departments was a mystery to me.

Sterling did not share our increasingly militant and nationalistic rhetoric, or our reactions to the racial climate on campus, which culminated in a takeover of the Bursar’s Office in the spring of 1968. Though Sterling did not participate in our actions, he never openly opposed them. On one occasion he let a group of us, grads and undergrads, hide in his apartment for one night while we were ducking possible arrest by the Evanston police.

Generally soft-spoken and well-mannered, Sterling responded a different fashion on at least two occasions in, when faced with the abusive treatment of Black women. I remember students coming into the cafeteria, telling the table that Sterling, swinging a golf club, had threatened a white man who had slapped a Black woman on a street in downtown Evanston. The second incident, which John Higginson reminded me of, involved Sterling punching a white man down two flights of stairs for a similar offense. There were a lot of ways to be Black in those days and Sterling had his.

In an indirect way, Sterling was responsible for me coming to the University of Massachusetts Amherst. During the summer of 1968, after the successful takeover, the Northwestern administration gave the Black student organizations funds for a summer program. With Sterling’s help, we put together a series of speakers that included Sterling Brown (Sterling’s namesake), and Michael Thelwell. Mike, a student of Brown’s at Howard University, had enrolled in the English department at UMass, on the recommendation of Brown who was a longtime friend of Sidney Kaplan. Sterling Brown was one of my favorites among the Howard faculty members who would be gathered in my mother’s office when my sister and I stopped by on the way home from school. I welcomed the opportunity to see him again and, after dinner and a glass of bourbon, to hear the uncensored versions of the stories he’d cut off when my sister and I came into his presence as children.

I had not seen Mike since my freshman year at Howard, when we met in the Honors Program. Based on this reconnect, three years later Mike asked me to join him in building the W. E. B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies at UMass. One of the things that sparked my interest in Mike’s offer was Sterling Stuckey’s seminal essay “Through the Prism of Folklore: the Black Ethos in Slavery,” which had been published in the Summer, 1968 issue of the Massachusetts Review—not in Negro Digest/Black World or the Journal of Negro History. There was something going on at UMass that was worth a looksee. Thanks again to Sterling.

Sterling and I both agreed and disagreed about various aspects of the history of African Americans. We joined together in confronting George Fredrickson in his seminar on “The History of the South,” when he passed out a syllabus with only one book written by an African American. I questioned the academic validity of such an approach. When challenged by Fredrickson to offer some suggestions, Sterling and I hastily drew up on the back of my copy of the syllabus a list of possible books that would begin to address our concerns. To his credit Fredrickson took us seriously, and became a staunch supporter of Black student protests, an advocate of adding courses on the African American experience to the curriculum of his and other relevant departments, and a leading historian of how beliefs in racism and white supremacy played a defining role in U.S. History.

Sterling and I differed over the basic thesis of Slave Culture. I thought that Slave Culture actually made more sense as two separate books: one on slave culture, the second on the nature of Black nationalism and its relationship to the life and thought of Paul Robeson. I was not persuaded by Sterling’s attempt to link the two subjects, either conceptually or historically. I presented my views in a session devoted to the book at the annual meeting of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, with Sterling as respondent. He disagreed vehemently and did not speak to me for several years thereafter. He took my analysis as a repudiation of his entire project, which it was not. I regretted the misunderstanding and its consequences, but saw no clear way to remedy the situation.

The letter that follows was written in part as my effort at reconciliation. Sterling graciously accepted it as such, and later sent me a copy of a volume of his mother Elma Stuckey’s collected poetry. Elma Stuckey was an underappreciated member of that group of brilliant women writers based in Chicago that included Gwendolyn Brooks, Margaret Burroughs, and Margaret Walker—upon whose shoulders the poets of my generation stood. This gift from Sterling is one of the most cherished books in my library. I offer this letter, written fourteen years ago for a different purpose, as my final thoughts on my friend, guide, and comrade P. Sterling Stuckey, a gentleman and a scholar.

January 19, 2004

Dear Sterling,

I have been going through my “papers” and came across the enclosed items on the Amistad Society. I don’t know if you share my packrat tendencies, but I hope you find them of interest.

I also want to take this opportunity to express to you my gratitude for the influence that you exerted in getting me to commit to the study of history as a profession. This past year, with the deaths of Herbert Aptheker and Augie Meier, I have had several occasions to talk about my interactions with them. Each time when I was asked if they were the ones who sparked my interest in African American history, and in the scholarship of Dr. Du Bois, I answered truthfully that in fact that was not the case. I then explained that it was my involvement with you and the Amistad Society that introduced me to the works of Herbert Aptheker, and that it was your deep reverence for Du Bois that compelled my revisiting his works that I had already read and exploring the entirety of his life and work. I will never forget the time that you brought out a copy of The Suppression of the African Slave Trade, which you had carefully wrapped to protect it against the elements. You didn’t let us touch it too much, but the point was made. How could one even pretend to be a student of the lives of Black folk without first engaging Dr. Du Bois? That insight, and the notion that the study of African American history was in itself an important part of the fight against racial oppression, spared me the burden of constantly debating the relative value of activism versus scholarship. You choose what you like, or are good at, and go on.

I am going on a bit long here. I just wanted to thank you for the important role you played in my life and to express my appreciation and gratitude. I hope and trust that all is going well with you and your family. Again: many thanks.

Sincerely,

John Bracey

**************

Rest in peace dear friend.

P. STERLING STUCKEY was a renowned historian of African American history and culture, best known for his seminal 1987 work Slave Culture: Nationalist Theory and the Foundations of Black America.

JOHN H. BRACEY, JR.,. was for many years chair of the W. E. B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where he has taught since 1972. Most recent of his many published works is SOS: Calling All Black People: A Black Arts Movement Reader (University of Massachusetts Press, 2014), co-edited with James Smethurst and Sonia Sanchez.