Massachusetts Reviews: Kill CLass

- By Allison Bird Treacy

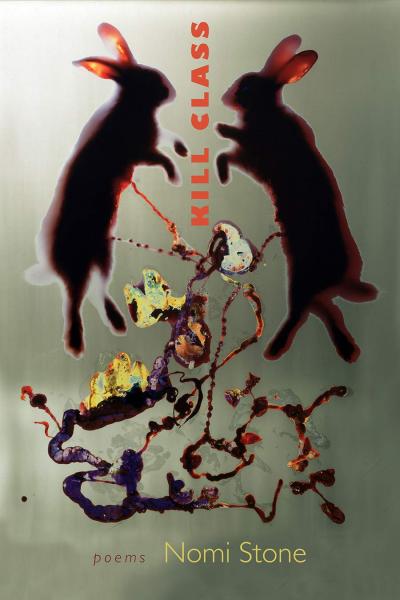

Kill Class by Nomi Stone (Tupelo, 2019)

Living as we do in a time of ceaseless, overlapping wars, I would venture that most Americans believe that we know how soldiers prepare for war, through basic training and boot camp, the persistent physical trials of young men to ensure their strength. In order to enter into Nomi Stone’s incisive second collection, Kill Class, however, we have to let go of this vision of military training, and follow her through the vortex of the anthropologist’s camera. There we encounter Pineland, the military training ground that “has room for whatever the world does to itself.”

Home to a special class of war games, Pineland can be anything, but today it’s Iraq—any city there, any Middle Eastern town, really. Here, soldiers and Iraqi immigrants enact what will happen in real war. And, drawing on Stone’s time doing anthropological research in such a mock village, her speaker invites us to encounter war and its inhabitants in a new way. In “Quadrant,” Stone writes,

. . At a military technology fair in Orlando

you can purchase a village in a box.

Just add people: live inside it for a time.

Kill Class is the box and the people inside are trying to survive a very real brutality, despite the fact that each Iraqi is a role player trapped inside, the Americans holding the box. And in order to understand the events, we need to slice away the cover. To this end, knives populate the world of Pineland.

One particular knife appears repeatedly. Inside the boxy world of fake classrooms and police stations, the anthropologist discusses village life and the militia with Omar. There

Omar shows me the knife, scimitar-curved, that hangs

on the wall at the police station. He takes down that knife, cradles it

like a guitar, plays a song.

In his hands, as in these poems, a knife can be a tool of creation, and when Omar takes up the knife like a guitar, we are forced to grapple with the space between the military and the domestic. Not only is Kill Class set within the rehearsal of war, rather than the war itself, but it offers the reminder that whether in practice or reality, war is always someone’s daily life. Stone, then, writes from a space shared with so many other contemporary poets, all of whom grew into adulthood in a world shaped by America’s global military ventures.

Part of what makes Stone’s work, along with that of other poets of modern, domestic war, so striking for readers is her ability to drive home American citizen’s complicity in harms. This is why Kill Class reads so well alongside other recent releases such as Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic or Emilia Phillips’s Empty Clip, a collection with a particular interest in gun violence. In what is perhaps Kaminsky’s most recognized poem, “We Lived Happily During the War,” for example, the reader must grapple with the blame: “And when they bombed other people’s houses, we//protested/but not enough.” In contrast, Stone’s work, as an anthropologist-poet, demands that the reader enter not in protest but in observation, to understand what those who must train Americans to destroy their country already know. As she writes in “Crying Room,” “consolation is impossible when you play/someone who is home and you can’t cry/for home.” So often allowed to escape culpability, Stone’s poetry is part of a new generation of writers who hold American readers firmly within the scope of blame and reckoning, much as Denise Levertov did during the Vietnam War. We are left in the silences and white space of Stone’s lines to meditate on our responsibility.

Despite its commitment to revealing the human side of Pineland, specifically from the Iraqi perspective, one of the most striking elements of Kill Class is the distance the participants must maintain from the game – the same distance that American civilians are casually permitted. The players, on the other hand, are reliving their past experiences of war and trauma; there are dead sons, lost limbs and homes, shattered skies, and if the employed players are going to survive, they cannot come too close. That’s why, when the anthropologist-speaker ventures out to play the game herself and is asked to kill a rabbit, the animal’s death feels so vulnerable to the reader.

Consider: in the war games, everyone else plays dead—the poem “The Notionally Dead” describes how to die in place, how you must “Write your eulogy, a pedagogical exercise to reinforce tactics”– but the rabbit does not have the luxury of preparation. It is the speaker’s pet, in a way, the others telling her “this is yours. Feed it. For now, feed it” and when she tries to refuse, it is impermissible. In a heartbreaking moment, she is told that there is no choice but to slaughter the rabbit. The men close in around the speaker, the only woman on the hike:

I have a choice. Let me be perfectly clear,

I say. It is not happening.

The men make a circle

The pines make a circle

You need to hold

the lens. They are tying together

the legs the animal

screaming They raise

the stick The legs are in

my arms The legs are in my arms.

What is so painful about this moment is not just the rabbit’s death, but the speaker’s inability to choose its fate or her own as it is forced into her arms. Every time the speaker and the others engaged in the war games at Pineland leave the site, the reader hears about their choices. There is the one practicing for his naturalization exam, and Yusuf who “wants to help the Americans as he thinks this is the path to security & prosperity.” These are choices complicated by American violence abroad, by the vulnerability of living in an Arab body in the American South, but they are some kind of choice. Poems speak of attempts to make a family proud or to avoid being victimized back home for acting as an interpreter. And though the anthropologist attempts to make a choice, she is denied.

Kill Class is defined by its moments of tenderness as much as its descriptions of real/not real horror, and in this way it is like so much writing about the body and trauma. In the short poem, “Count Your Kills,” the speaker asserts a notion heard so often when talking of love, how it breaks us down. Ordinarily, though, this would be followed by the notion that we are remade anew. Instead, Stone offers this variation:

We disassemble each other:

we make each other disappear.

In the room lit like an oven

we kill what we hold

in our arms, gentle body

of sand and wind.

In this light, to be disassembled is the first step toward being both treasured and forgotten, how death is cradled like an infant. Mirroring the rabbit in the speaker’s arms, how it must die and be eaten, the slippage between light and fires and ovens giving way as ash and sand in the wind. When we go to war somewhere outside the Middle East, Pineland too will give way to somewhere else, though it will still be Pineland, just as it was the Soviet Union before it was the Middle East. And those who play at war and those really caught up in it will cradle their losses, and the vulnerable will give themselves over, act as the enemy if that is the best choice among many bad ones. As for the anthropologist, she will observe it all and tell about it.

ALLISON BIRD TREACY is a poet and essayist based in the Pioneer Valley. Her work has appeared in Cider Press Review, the Pittsburgh Poetry Review, and VIDA: Women in Literary Arts.