10 Questions for Steven Cramer

- By Abby Macgregor

Jake says: “first time I recall wanting to die I was eight.

When I tried and nearly did I really wanted to live.”

—from “South Belknap”, Spring 2019 (Vol. 60, Issue 1)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you wrote.

If I go “deep background,” I remember trying to write a sci-fi story when I was nine or ten. I made all the characters say the opposite of what they meant (the Queen of Mars tells her guards to “release” the interloping Earthlings when she wants them arrested.) The story remains unfinished. As a college freshman, I started writing miserable T.S. Eliot imitations (I believe The Fisher King made an appearance!), some of which AGNI—at that time more a college journal than a national literary magazine—printed. Mercifully, those early issues are inaccessibly archived, though I’d prefer them pulped.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

At sixty-five, I’d like to think I’ve become, more or less, my own writer, but I know that’s always only more or less the case. I did not grow up in a literary or religious household, so literature, or the key iconographies of Western culture, didn’t enter my bloodstream early on. Hearing a brilliant high school English teacher recite Eliot made me want to become . . . a high school English teacher. Antioch College changed my life (as college ought). I met students already writing poetry—Stuart Dischell, Sarah Gorham, Askold Melnyczuk, among others—and passionate young teachers like Eric Horsting and Ira Sadoff. It was a lucky time. Emily Dickinson seems to me to be the American Shakespeare, but dare I claim influence? “Dare you see a Soul at the White Heat?” A memoir, Frank Conroy’s Stop-Time—which I’ve taught scores of times—has probably taught me as much about metaphor as any work of poetry. I’ve tried not to get so jaded that I won’t learn from those younger than me.

What other professions have you worked in?

I like the “other!” Other than what? Other than writing poetry? Is that a profession? Other than teaching? Teaching is indeed what I currently “profess”; writing poems is what I must. From my late teens until now, I’ve washed dishes in a hospital kitchen; mowed lawns; cleaned toilets; shuffled various kinds of governmental forms; managed copyeditors (without ever having copyedited myself); written marketing copy; played Cerberus before the Gates of Poetry at The Atlantic Monthly; and then taught, taught, taught at any university or college that would have me (six, at last count). In 2003, I founded Lesley University’s Low-Residency MFA Program in Creative Writing, directed it for twelve years, and now teach in it only, ecstatic not to be making the decisions.

What inspired you to write this piece?

“South Belknap,” I hope, conveys a very personal subject via a very impersonal viewpoint. The speaker—or, really, the narrator—witnesses and presumably participates in a group dynamic taking place (again presumably) on the campus of a psychiatric hospital. Much of what’s spoken in the poem was indeed spoken in a room on the campus of a psychiatric hospital, though some of the dialogue comes from whole cloth. When the viewpoint turns to and then out of the window (like a camera panning, I hope), exclusively visual imagery supplants talk. I don’t recall how, or if, I was inspired to create that trajectory from the said to the seen. Perhaps this sounds immodest, but rereading the structure of “South Belknap” inspires me—to gratitude that I have an imagination.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

Not really, and I’ve never actually thought about that, so it’s a good question. Every decade or so, I write a poem called “The Glen.” I wrote one in graduate school; one appears in my third book, Dialogue for the Left and Right Hand; and I finished one just recently. That glen was a large, remote wooded area somewhere in South Orange, New Jersey. As I recall, we kids tunneled through a culvert to get there. Nothing remotely Midsummer Night’s Dream-ish ever took place there—mainly we played with sticks and came back—but my memories include flashes of nakedness. Nothing abusive, just preadolescents getting nude because they could.

Do you have any rituals or traditions that you do in order to write?

I used to work according to a fairly strict morning schedule, at my desk, in my office, promptly by 8:00 (or was it earlier?). For the last two years I’ve written almost everything on a laptop, supine on the living room couch (my location right now!). I’ve noticed no difference in the quality, for good or ill, resulting from this change of venue. The quality of my study, and the area around the living room couch, has changed considerably for the worse.

Of course, smoking cigarettes used to be the writer’s go-to ritual. I quit around age thirty, convinced I’d never write again. Many toothpicks and cinnamon sticks (the latter recommended by the late Thomas Lux) kept me at it, but I still can’t clock the number of hours I did back when I was killing myself.

Who typically gets the first read of your work?

Who typically gets the first read of your work?

Me, and, after me, my wife Hilary, who graciously helps me divide the half-baked from the mortifying. I’ve been swapping poems with Teresa Cader and Joyce Peseroff for—what? Over two decades? Without them, I’d be lost. Meeting with them keeps me writing and keeps me honest (as honest as I can be). I also swap poems with Joan Houlihan, and I’ve recently had the unexpected pleasure of reconnecting, after decades, with one of my best chums from Iowa—the graceful and under-read poet Thomas Swiss. We essentially co-wrote each other’s first books, and maybe our second books as well, and now we’ve fallen right back into our exchanges, acutely useful to both of us.

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

Music. I drummed by instinct, and instinct only takes you so far, but I adored the free play of group improvisation. Really, though, I envy almost every art form other than my own: I can’t imagine what composers hear in their heads, but I wish I could; painters get to work and listen to talk radio; actors get to feign who they really are. Prose writers (some of them) get paid. My dancing rivals Elaine’s from Seinfeld, and my singing provokes horrified looks of sympathy. Who would choose to be a poet?

What are you working on currently?

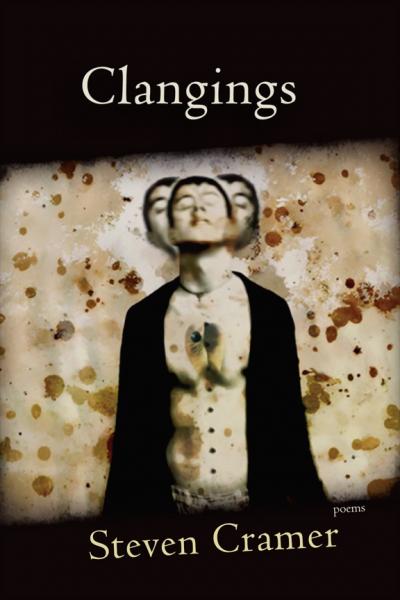

I’ve finished a collection currently entitled Listen. Since my previous collection, Clangings, was such an atypical book for me, I guess the poems in Listen return, somewhat, to the lyric mode of earlier work. Whereas Clangings was obsessive in psychology and formally fixated—though polyvocal—the poems in Listen try out many different styles and structures: prose, adaptations from other languages, fixed form ghostings, domestic settings, public settings, narratives, junctions and disjunctions. One of the central subjects of Listen—depression—constitutes, for me, a deeply intimate experience as well as a personal and more broadly human revelation. I’ve tried to render that experience and those revelations both intensely and accessibly through the prism of art. I’ve written quite a clutch of poems since assembling Listen. Do some of them belong?

What are you reading right now?

I read more restlessly than I wish I did. Quite a few half-read novels, biographies, and general nonfiction lie spine-up on my various floors, wings spread. Contemporary poetry, for me, comes from a mixed grab bag. I used to review regularly, and read more systematically. Right now: is Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic really as good as so many say? I think it may well be. James Longenbach’s poetry and criticism have provided deep rewards. Some other poetry contemporaries: Forest Gander’s Be With; Terrance Hayes’s American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin; Bob Hicok’s Hold (when someone’s that funny, I’m relieved they didn’t turn their gift toward a life of crime); and the always magnificent Chase Twichell’s Things as It Is. Of the eternal dead, Dickinson, Rilke, and Yeats sing me to sleep many nights. I’m usually reading some book on the brain, but appear not to be right now. I love the godless thinkers: Dawkins, Harris, Hitchens, and Pinker. Rachel Kadish’s weighty novel The Weight of Ink is worth every hour I’m devoting to it (I’m a slow reader). Sometimes, in the middle of a semester, a creative writing student of mine will ask me what I’m reading. I answer: you!

STEVEN CRAMER is the author of five books of poetry, most recently Clangings. His poems have appeared in numerous journals, including The Atlantic, Paris Review, and Poetry. Recipient of an NEA fellowship, and two fellowships from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, he founded and teaches in the low-residency MFA program in Creative Writing at Lesley University.