Massachusetts Reviews: Moxie

- By Allison Bird Treacy

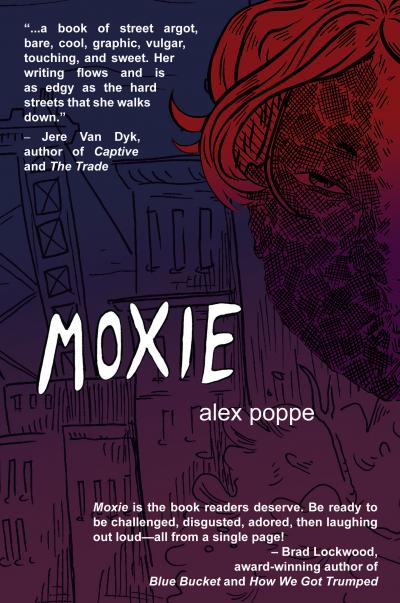

Moxie by Alex Poppe (Tortoise Books, 2018)

Scott Hamilton was wrong when he said that the only disability in life is a bad attitude. In fact, you ask many self-described disabled people, a bad attitude is just our other disability. That’s why, when an abled writer puts a disabled character at the center of a story, as is the case in Alex Poppe’s debut novel Moxie, the text must walk a fine line: avoid the inspiration porn trap.

Often ascribed to the late disability activist, journalist, and comedian Stella Young, inspiration porn describes the majority of mainstream disability content that objectifies disabled people as sources of inspiration for the abled reader or viewer. And the narrative trope of overcoming disability, even if only by getting out of bed in the morning, has been popular in publishing lately, particularly as crossover hits that become movies with non-disabled actors playing disabled characters. That’s what happened with the YA hit Wonder, which like Moxie, features a disfigured main character, or the pop-romance Me Before You. Abled readers and viewers love to be inspired by disabled characters, to the detriment of actual disabled people.

So how does Poppe fare in avoiding the inspiration porn trope? Her beginning is tentative. Former supermodel Jax is still in a state of mourning for her career. It’s only been a few months since a bombing in Marrakesh tore away half her face, and that mourning makes it difficult to determine, at least at first, whether Jax has a bad attitude or is self-pitying, self-pity serving as the other major trait of disabled character by abled authors. What seems like pity, however, quickly reveals itself to be integral to the humor and tension of Moxie. Poppe has a deft hand with crude language and body horror and twists these moments into graceful linguistic play, an ability that’s revealed in Jax’s early, self-negating description:

Kissing distance to the sky, I am kind, I am beautiful, I am whole. My right cheek is not the texture of crunchy peanut butter, nor is it singed dark like chocolate coating. I do not snap the rubber band on my wrist until pain-darts pierce my skin, shrapnel tearing. I am half-dark, half-light: two faced when turned-cheek.

In lines like this, Poppe’s writing draws the reader into Jax’s experience of disability and trauma with language that simulates her narrator’s personal disorientation, but it’s this same gruesomely funny language that gives Jax momentum to move forward. Looking beyond the narrow redemption narrative, Moxie sets out to transform Jax from a drunken late-twenty-something child into a self-sufficient woman – and that starts by taking responsibility for another living creature.

Enter Moxie. Moxie is, at least briefly, the rescue dog who is supposed to be Jax’s new companion. Instead, when Moxie runs off from the dog park, her disappearance forces Jax to pull herself together and start picking up the pieces of a life in which it seems everyone is leaving her behind. Though to be fair, by launching a high-powered modeling career in her early teens, Jax left everyone else behind first. What remains of her past needs to be assembled with new pieces into a viable future, but all she can see are the shards after the bombing, made plain on the page through Poppe’s distinctive sentence fragments.

Sentence fragments litter Moxie as a kind of linguistic shrapnel, accompanied by sharp, descriptive moments that leave the reader off-kilter as Jax goes about her day. Their effect is to offer both inner monologue and discomfort. At a photo shoot, Jax waits for the talent to show up and thinks about Moxie. “The sky turns the color of cue chalk. Wonder where Moxie spent the night. Was going to look for her after the shoot but cock knows how long this will take.” Jax lives in partial thoughts and incomplete plans, a mental extension of her half-burned face.

Sentence fragments litter Moxie as a kind of linguistic shrapnel, accompanied by sharp, descriptive moments that leave the reader off-kilter as Jax goes about her day. Their effect is to offer both inner monologue and discomfort. At a photo shoot, Jax waits for the talent to show up and thinks about Moxie. “The sky turns the color of cue chalk. Wonder where Moxie spent the night. Was going to look for her after the shoot but cock knows how long this will take.” Jax lives in partial thoughts and incomplete plans, a mental extension of her half-burned face.

Throughout Moxie, Poppe’s language is at its finest when she’s innovating on ordinary phrases. When Describing Marlowe, for example, a preteen who befriends and accompanies Jax in her attempt to rescue Moxie, Poppe writes that “Her mouth is full of hatred teeth.” Here, even the most basic elements of the body are displaced and ascribed unusual qualities. Are hatred teeth sharp? Are they too white or too straight? As readers, we don’t need to know quite what the phrase means to understand how they flash in this child’s mouth and represent the threat Marlowe poses to Jax’s current state. The writing navigates by feeling its way through daily moments, as though Jax is still blinded by the bomb that burned away her face. Every day begins anew in this glare.

In a scene that repeats like an endless mirror through the book, Poppe describes Jax’s hangover as, “somewhere between drunkenness and consequence. My forehead flares blue/red. At least the pillow beside me is empty: no lying dismantled by a mistake.” A mistake sums up how Jax feels about nearly every encounter in the months after her injury, from the ex-boyfriend who last saw her at the height of her career to the journalist she meets while dressing a photoshoot set and, of course, during every interaction with the charming and frustrating Marlowe. What she doesn’t realize, though, is that those mistakes are what will reassemble her; Jax can’t be broken down any further at this point. Moreover, each of these people has, in some way, chosen Jax – and this is what will force her to choose herself as she is now, rather than as she once was.

This is one of the great problems of disability: choice. To be disabled or disfigured is often to be taken in out of pity, not in equality, and to have your choices circumscribed. That was, ultimately, why Jax adopted Moxie – and when Moxie disappeared, Jax felt like she didn’t have anyone in her life who would choose her. Frieda landed a job that would take her across the country. Her ex-boyfriend was dating someone new. But then there’s Lukas, the journalist who keeps calling her, and Marlowe, who won’t stop texting Jax (and whose father is holding Moxie hostage). People are choosing her, even if they aren’t people Jax would choose herself.

Jax never does get Moxie back. She finds her – early on she chases down Marlowe’s father, who had found the injured Moxie and renamed her Desdemona – but can’t convince him to return the dog she never registered, and in the end it doesn’t really matter. Set in the middle of a loyalty plot, Moxie or Desdemona, whatever you want to call her, will choose socks over people any day; Jax can’t compete. Even if she was given back, as Marlowe’s mother urges, Jax knows what she wants. “I want to be chosen,” Jax says, as everything comes into focus. Taking that back is everything. To be chosen means more than just being seen, more than just being a cover model or a star. It means you matter. Now Jax just needs to act like that’s true, and it’s a challenge she’s finally ready to tackle.

ALLISON BIRD TREACY is a poet and essayist based in the Pioneer Valley. Her work has appeared in Cider Press Review, the Pittsburgh Poetry Review, and VIDA: Women in Literary Arts.