10 Questions for Chris Forhan

- By Abby MacGregor

They said dragoon and sconce and prithee then

and cursed not their work—rock-hauling, hog-murdering, thatch-gathering,

even as it stiffened their fingers, wrenched legs into question marks.

—from “What Is the Cause That the Former Days Were Better Than These?”, Spring 2019 (Vol. 60, Issue 1)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you wrote.

My earliest extant poem is one I wrote when I was eight and gave to my mother for Mother’s Day. I put a carnation in the poem so that I had a rhyme for “celebration”—already I was letting form determine content. A couple of years later, I wrote a short novel that my fifth-grade teacher thought impressive enough to read aloud to the class. In the story, heavily influenced by the TV series The Time Tunnel, two friends travel through time and get stuck, unable to return to their original era and place. With no small amount of clumsiness and melodrama, I wrote, in the final sentence, that they would forever be trapped “in the slimy mitts of time.”

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

It is always difficult to differentiate between writers I merely love and writers who have actually influenced me. During my early years of taking writing seriously, I read many poets with passion—I became fanatical about them, absorbed them, then moved along, although what they taught me is probably still somehow in my system: Keats, Whitman, Dickinson, Hopkins, Stevens, Roethke, Ashbery, Plath, Kinnell, Strand, Simic, Charles Wright.

I am willing to say that the most important poet for me is Stevens. The contemporary poet I most wish I could write like is Laura Kasischke.

What did you want to be when you were young?

When I was in elementary school, it was my understanding that I would become a member of my hometown professional basketball team, the Seattle SuperSonics.

What inspired you to write this piece?

With most of my poems, the inspiration is murky, difficult to determine, but with this one, the evidence is in the title: the poem originated in my reading of the Bible. In Ecclesiastes, I happened upon the instruction, “Say not thou, ‘What is the cause that the former days were better than these?’” I took this personally, since comparing former days to these is something of a vocation for me. I considered it a challenge to do exactly what scripture commands me not to do. I suppose I have therefore lessened my chances of salvation, but I didn’t have much of a shot at that to begin with.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

I grew up in Seattle and, since leaving for college in 1978, have lived mainly away from the city. Still, its landscape and flora and weather impressed themselves upon my imagination early, so when I think of rain, I still think of northwest drizzle; when I imagine a tree, I see a Douglas fir.

Is there any specific music that aids you through the writing or editing process?

No music. In all stages of the writing process, I need absolute silence. It is not a matter of superstition; I want to sink deeply into my imagination and into whatever music the language itself is making, so any sound from outside of me pulls me away from what I am making—it breaks the spell. I’ll use ear plugs if necessary. I once had a residency at an artists’ colony, and my assigned room was near a staircase that a staff member swept with a hand broom—slowly, meticulously, step by step—each morning. The shoop, shoop, shoop of the broom at 9:30 every day was enough of a distraction that I requested a change of rooms. Please understand that I am not proud of what this anecdote reveals about me.

Do you have any rituals or traditions that you do in order to write?

Nothing unusual or elaborate. For the writing of poems, two things—beyond the silence—that are necessary are a pen (I am not a fan of pausing to sharpen pencils) and a college-ruled spiral bound notebook. When I was nine or ten and began writing songs, I used such a notebook for writing my lyrics; when I stopped inventing melodies and the words remained, the notebook became a place for poems. In the fifty years since then, I haven’t felt a reason to change. I write each poem, draft by draft, in such a notebook and do not type the thing up until as late in the process as possible.

Who typically gets the first read of your work?

My wife, Alessandra Lynch, also a poet. She usually lets me know when I’m being glib or predictable.

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

Music. I might not need to write poems if I could play the saxophone half as well as Lester Young or write songs as inventive and melodic and true as those by John Darnielle of the Mountain Goats.

What are you working on currently?

I wrote a memoir a few years ago and caught the prose bug, so I am writing another book of prose: a kind of epistemology of popular song—a meditation on the way music affects our imaginations. I am enjoying listening more closely than I ever have to songs by people such as Robert Johnson, Billie Holiday, Frank Sinatra, Buddy Holly, Howlin’ Wolf, Nina Simone, Neil Young, the Temptations, and Tom Waits.

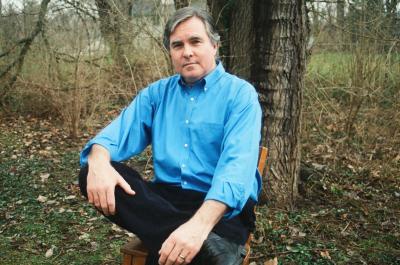

CHRIS FORHAN'S most recent book is a memoir, My Father Before Me. He has published three books of poetry—Black Leapt In; The Actual Moon, The Actual Stars; and Forgive Us Our Happiness—and has won an NEA Fellowship and two Pushcart Prizes. He lives with his wife, the poet Alessandra Lynch, and their two sons, Milo and Oliver, in Indianapolis, where he teaches at Butler University.