Even a Number

- By Erri De Luca

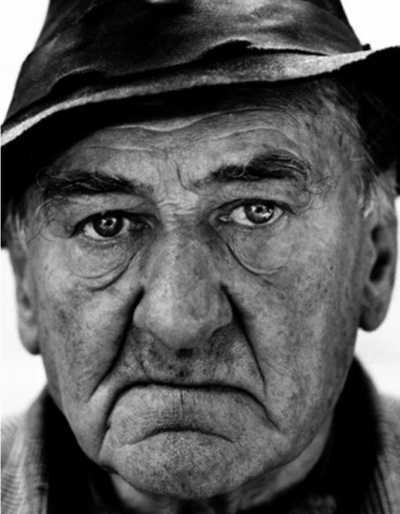

Danilo De Marco is a photographer who still works with film, in black and white, and then goes into the darkroom to develop and print, under the glow of a red light bulb. He says digitalization erases the texture of his images.

One of his recent exhibitions in Udine displayed a collection of the oversized-format faces of aging partisans. Those that reached the age to become grandparents carry history carved into the map of their expressions.

Danilo has me read a letter he got in response to this exhibition, written by a young woman, thirty years old. Her grandfather had been a partisan, but she didn’t manage in time to get the stories directly from him.

Amid the oversized faces in the exhibition hall, she writes, she felt she was among family—a niece who’d come for a visit. There were documents telling their stories as well as that of her grandfather, a prisoner in the camp at Dachau. She thought it through, ruminated over it, and then decided she wanted to make a gesture I’d call religious, in the literal sense of the word, an act analogous to a knot. She had her arm tattooed: the internment number of her grandfather, inside a triangle with the point down, one of the symbols sewn into uniforms to identify groups of prisoners.

“When I look at that number on my skin and then see my eyes reflected in the mirror, I feel my grandfather is with me. I wear it proudly, as if I were carrying both weight and a medal.”

And so it is, for someone who decides to enlist in a history that happened before she was born. She assumes its burden and displays it with pride. She wished to declare herself heir to a history, a bequest most lasting than any testamentary disposition.

Tattooing used to be a practice among prisoners and sailors, a way to thicken their shells. Today it’s the widespread expression of a desire to make one’s own surface unique. Skin as blank paper for an indelible illustration.

The file number from a concentration camp doesn’t lie at the surface. Its motive sinks down to the bottom like an anchor. Whoever asks her about that tattoo will learn quickly who they have before them.

I knew some of those faces that Danilo fixed for us, barely in time. I don’t wear tattoos on my skin, but I do have, in the palm of my hand, the mold left by a handshake—with some of those who held weapons in the fight against oppression and dictatorship.

The history that concerns me has been made by hands.

In the preface to Danilo’s exhibition in 2015, I wrote that people leave only one thing that continues to belong to them: their good name, an asset that spreads through descendants. A name is your legacy.

From a young woman’s letter I’ve learned it’s even possible also to leave a number. To be displayed with pride.

Erri De Luca is a novelist, essayist, translator, poet, and one of Europe's best-known writers. His most recent novels are La natura esposta (Feltrinelli, 2016) and Il giro dell’oca (Feltrinelli, 2018).