Lazarus and Liberty

- By Peter I. Rose

Extending “World Wide Welcome”

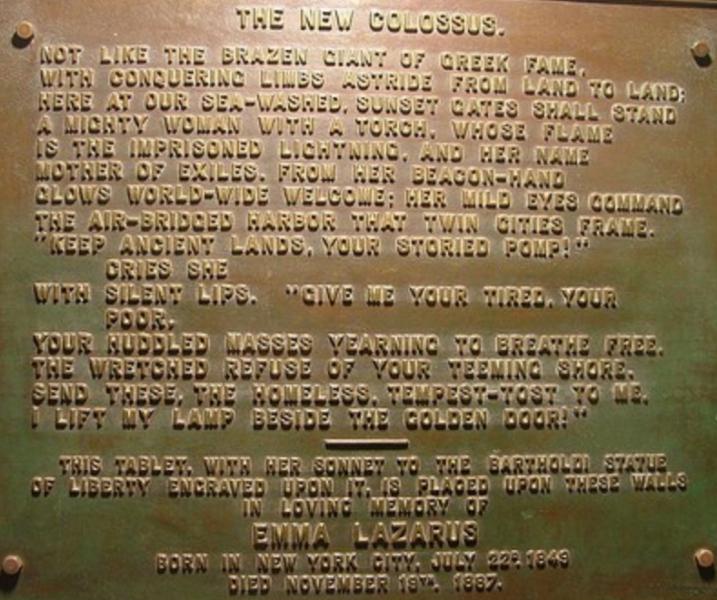

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Over the desk in my study is a fascimile of the handwritten and self-edited text of the well-known sonnet that appears above. It was titled “The New Colossus” by its author, Emma Lazarus.

The copy of the poem was given to me fifty years ago by the University of Chicago sociologist, Everett C. Hughes, after I spoke to his students in a talk I called “In Aid to the Tempest-Tost.” Everett, who himself had been a pioneer spokesperson for the rights of immigrants and minorities, had long known of my admiration for Lazarus’s work. He knew that for me the lyrical words of the poem had become a personal anthem, just as its message continued to offer visions of hope and promise for millions of those she had labeled the “tired,” the “poor,” the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

Lazarus’s words have remained singularly important to me over a long career of studying about race, immigration, and the dilemmas of diversity. They speak to many others as well, including my Dutch wife, a “hidden child” and Holocaust survivor whose first view of America in 1947 was of that “mighty woman with a torch,” seen from the deck of a Greek ship carrying several hundred refugee children in its hold. Hedy says she will never forget that sight, nor will she ever forget learning to recite the poem and feeling proud that she, too, was now an American.

For years, like so many others, I thought the idea for Lazarus’ poem was inspired by her own experience as a dispossessed person seeking asylum and a new life in America. But, looking into her personal history, I learned that this was far from the case.

Emma came from a wealthy New York family with roots in this country going back four or five generations, to a time that predated the American Revolution. A descendant of the first contingent of “Hebrews” to come to the colonies on the eastern seaboard, her ancestors were among the thousands of Sephardic Jews who had fled during the Inquisition from Spain and Portugal to Holland and several of its possessions and later settled in New York.

She was born in 1849 and died in 1887. In that short life of only 38 years, a woman with little formal education became a translator of Goethe, Heine, and others, a literary critic, and a writer of novels and plays and poems. She was also a political activist, favoring Progressive policies and the economics of Henry George. In the early 1880s, shocked by what she learned about the treatment of Jews in the Czarist Russia and in its Pale of Settlement, she became a tireless worker for immigrants, especially those fleeing anti-Semitic pogroms.

Some say it was her involvement in such causes that prompted her to agree to write a poem commissioned for the base of the Statue of Liberty. This may have been the catalyst, but her interest in the “tempest-tost” was universal, not parochial, as was her belief that there is strength in our diversity.

A pluralist before that word entered the vernacular, Lazarus felt it was not enough just to open the “golden door”; we also needed to facilitate the acculturation of those who passed through it, went through the processing center at Ellis Island, and moved on into their new communities to become active American citizens. She might have even been an inspiration for John Dewey, who twenty-five years after her death, spoke of the fact that, “the point is to insure that the hyphen connects instead of separates.”

Lazarus never lost her special concern with the scourge of anti-Semitism or for the folks who settled on the Lower East Side of New York, but she saw it as one cause in many to be served by generous supporters who would put themselves in the shoes of others, not a few inspirited by the “there-but-for-the-grace of God...” mentality. To that end she also worked in the settlement house movement and became a public voice for both immigrants and refugees, assuring in every way possible to help them to be able to stand on their own two feet.

To say that Lazarus would be appalled at the mockery made of her sonnet—and, implicitly, of all those who found her words encouraging—by Donald Trump’s Acting Comissioner of Immigration, Ken Cuccinelli, would be an understatement. Like her sonnet, Emma Lazarus was herself a Colossus, a true American giant in comparison to the xenophobic Lilliputians in today’s Washington.

At the time she was writing, the vast majority of those seeking refuge on our “teeming shores” were Europeans fleeing poverty and political persecution in the Great Atlantic Migration. While many of today’s newcomers still come from Europe, after the Immigration Reform Act of 1965, many more have come from the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and from across the Rio Grande. .

To deny their entry, as is currently proposed by neo-Nativists, belittles Lazarus’s call for “World Wide Welcome” and diminishes the nation.

The oldest refugee agency in the United States, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), which Emma Lazarus supported in its early days, is now, nearly one hundred and forty years later, focusing many of its programs on those most in need today: Muslim emigres coming to America from Syria, Yemen, and other places in the Middle East and North Africa—as well as those said to be “invading” our country from Mexico.

Nothing would please the poet more.

Peter Rose, Sophia Smith Professor Emeritus at Smith, is a sociologist and writer. His recent books include Tempest-Tost, The Dispossessed, Postmonitions of a Peripatetic Professor, and Mainstream and Margins Revisited: Sixty Years of Commentary on Minorities in America. In 2020 Routledge will publish his latest, Tropes of Intolerance: Pride, Prejudice and the Politics of Fear.