Yevgenii Yevtushenko: An Appreciation

- By Llyn Clague

To me, a young American in the ‘50s and ‘60s with a strong anti-Establishment streak and a poetry bent, Yevgenii Yevtushenko was a magnetic figure. After my six-month sojourn in the Soviet Union as a student learning Russian, his work appealed to me even more. I met him only a few times at public readings, and we were certainly not personal friends, but he has had a lifelong influence on my poetry.

In one important respect, Yevtushenko, who died on April 1, 2017, represented a contrast to American poetry at mid-century. A number of our prominent poets—Lowell, Plath, and others— suffered from mental illness, suffering which inspired, and was integral, to their poetry. At a time in my life when I questioned my own emotional stability, as well as my incipient addiction, Yevtushenko stood as a figure of sanity, of finding an emotional health, in a life of poetry.

As a poet I am akin to what the Navy calls a mustang—an officer who did not go to the Naval Academy, but rose from the ranks. I am an autodidact in poetry (an ABD, but in history), and much of that self-teaching has been in German and French, as well as Russian, poetry. Until I retired and began to write poetry “full-time,” my career was in business.

During the decades I wrote mostly for the drawer, my admiration of Yevtushenko went beyond his role as a gadfly to the Soviet regime. He was, of course, also very successful at surviving, and thriving, in that regime. I didn’t want an academic life, but I also didn’t want the starving-artist-in-a-garret life. I wanted to be successful in society, at the same time that I held a deep anti- stance toward it.

Yevtushenko’s life centered around that pull-and-tug. A key poem expresses that directly. His “Two Cities” (translated as “The City Of Yes and the City Of No”) describes one city where everything is great and another where everything is terrible (or at least pretty bad—much like Soviet society at the time). “Only,” he says at the end, in the happy place “it’s a bit boring,” and personally

Better let me be tossed around

to the end of my days

Between the City of Yes

and the City of No.

Let my nerves be strained

like wires

Between the City of No

and the City of Yes!

Yevtushenko’s embrace of polarity has great appeal. On the one hand, he is the internationalist (“I want to walk at will / through the streets of London, / … I want to ride / through Paris in the morning, / hanging on to a bus like a boy”)—and this when most Soviet citizens were, prisoners in their own country. In “New York Taxis,” he amusingly celebrates “New York is all mankind in one casserole” (“This morning [in a taxi] I jumped into Poland, / at mid-day into Haiti.”). On the other hand, he could lament, in “Goodbye Our Red Flag,” the demise of the Soviet Union and honor the sacrifices so many made to protect his homeland during World War II.

“Babii Yar,” Yevtushenko’s most famous poem, asks—implicitly criticizing the regime—why is there no monument to the Jews killed there? He writes, “Now I seem to be / a Jew,” and walks through Jewish history as if he were present at each epoch. And the poet ends by grounding this principled anti-Semitism in nationalism: “I am a true Russian!”

An issue of some urgency in our American culture at this moment is whether poetry can be universal, speaking for, or in the name of, others. A painting by Dana Schutz, a white artist, that uses the image of the murdered black teenager Emmett Till was attacked for appropriating material that, some have argued, belonged to black artists. Similarly, Ben Lerner in The Hatred of Poetry, discusses Claudia Rankine’s recent books:

Rankine confronts—as an African-American woman—the impossibility (and the impossible complexity) of attempting to reconcile herself with a racist society in which to be black is to be invisible (excluded from the universal) or all too visible (as the victim of racist surveillance and aggression). (65)

Can a white man understand or identify with a black woman? Poetry, in America today, rests on a widely held belief that it is rooted in an individual self: that it is “personal.” (Admittedly, there has been backlash: some poets, particularly academic ones, almost eschew the vertical pronoun.) Taking this belief to its logical conclusion, can any of us really grasp the life and experience of another, even a spouse? This kind of emphasis on identity, group or ultimately individual, drives us apart, into a kind of atomization. Lerner argues that “traditional lyric categories” do not address Rankine’s concerns, hence two of her books are more prose than poetry.

Yevtushenko didn’t pretend to speak, à la Whitman, for “everyman,” but in “Babii Yar” or in “Heirs Of Stalin,” a poem attacking those who might bring back tyranny, he did succeed in speaking to a feeling, or yearning, inside many, if not all of us. To those outraged at the injustice of the killing pit, those against tyranny. He celebrated what we humans have in common, rather than what separates us, both in terms of attacking the regime and celebrating life. (“Do I contradict myself? / Very well then I contradict myself.”)

This common-man theme opposed Yevtushenko to the stereotypical academic American poet, safe in a tenured job, writing cloistered “academic” poetry. (My anti-Establishment stance included “establishment” poetry.) He was a poet of Main Street, not some “Wall Street” of an esoteric, poetic establishment. I also opposed him to Wallace Stevens (but not William Carlos Williams), whom I see as totally divorcing his day job from his poetry—his day self from his poet. My ambition for myself was (and is) to write poetry for “ordinary people.” Yevtushenko, with poems like “To Incomprehensible Poets,” modeled that wish.

He may not be a “great” poet. He is less profound than Czeslaw Milosz, less poetically creative than Joseph Brodsky. Poets closer to home, like Andrei Voznesensky, Bella Akhmadulina, Osip Mandelstam, and especially Anna Akhmatova, may be judged more accomplished. Some, particularly the last two, suffered enormously under Stalinism and left us with a haunting poetry.

Like all the Russians, Yevtushenko translates (or is translated) badly. To give one example from the poem cited above, in the original Russian, all the attributes of the Yes City end-rhyme with da and those of the other with nyet, so you get a refrain of da-da-da-da and a rival one of nyet-nyet-nyet, wittily reflecting the superficiality of each and preparing the author’s rejection of such onesidedness.

In Russian, both straight and slant rhymes are infinitely easier than in English, and in his technically more interesting poems Yevtushenko does use such techniques skillfully. Particularly when the poems are read aloud, these sonic echoes do a lot to hold the poems together in the ear. And, indeed, his style and skill of presentation—he didn’t “read,” he recited from memory—is a further model for me. He freed himself from the physical book, but he didn’t go to the other extreme of pretending to be an actor. He simply, vigorously, presented poetry.

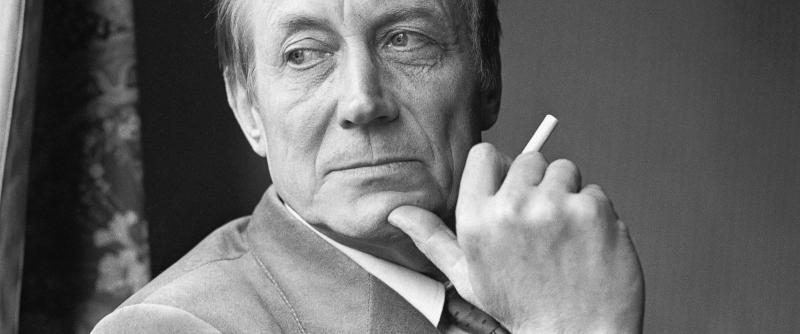

Yevtushenko was a force of nature. Very tall and thin, he had great presence, and there are stories that, even as a nineteen-year-old “waving his arms wildly,” he made an impression in Moscow literary circles. He wrote constantly, and many of his poems are unremarkable. But he connected with people—“ordinary” people but also the intelligentsia. Shostakovich’s Thirteenth Symphony uses Yevtushenko’s poetry (I saw a memorable performance once at Carnegie Hall). He also took swipes at “careerists,” as if he weren’t one himself. We all know those people, in academia or outside.

Yevtushenko, for me, will always be an inspiration—as a poet fully engaged, both personally and publicly—in the life of his times.

Llyn Clague lives with his wife in Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y. After a 35-year career in international human resources, He has published his poetry in a wide range of journals, including New York Quarterly, Mobius, Ibbetson Street Review, Pegasus, The Iconoclast, Main Street Rag, The Aurorean, and Palo Alto Review. His first book, Confessions: Selected and Edited, was released in 2007 by Ibbetson Street Press and his second, On Becoming a Poet Full Time, and third, Painting Sin, were published by Main Street Rag Publishing in 2008. For 5 years he was co-Managing Editor of Inprint.