10 Questions for Anita Felicelli

- By Edward Clifford

Paati lived at the edge of a minor fishing village, in a small gray house darkened by caliginous algae stains that streamed down its outer walls and along the edges of its clay roof tiles. She was their mother’s mother, a stern woman, darker than their mother, with a nose curved and knowing like the beak of a hawk.

—from “Tent Cinema,” Volume 60, Issue 4 (Winter 2019)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you wrote.

When I was sixteen, I wrote a short story about two skateboarding teenage boys whose lifelong friendship is disrupted when they fall in love with the same girl. One of them starts dating the girl, and the other sinks into a deep depression and starts thinking about the fun they used to have in the creek where the boys played as children. This story was full of longing and loneliness and purple prose. It got second place in a local newspaper contest for short stories by teens; I still remember the judges’ comment telling me I needed to gain greater control of my poetic language and metaphors.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

I read widely, and have my entire reading life, so it’s hard to pinpoint one specific influence. There are certain authors and books to which I repeatedly return for a way forward when I’m stuck. I read and reread George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss when I was little and I studied her novels, along with other early British novels, in college. She has a penetrating intelligence and cerebral curiosity about the world and ideas; she remains a North Star.

My understanding of Toni Morrison has deepened with age, and I read and reread her books— she was writing with herself, an excellent reader, as an audience, and it’s from the risks her genius novels take that I gain courage about my own vision. Jonathan Lethem changed the trajectory of my writing life in my twenties. Realism was wholly dominant back then, but when I read Lethem, I knew I had found work that fit the way my own mind so often works —a writer whose work is animated by a spirit of play.

The intensity of Adolfo Bioy Casares’ novellas Invention of Morel and Asleep in the Sun is something I work towards. I fell in love with the liminal spaces of Nella Larsen’s Passing in high school and have returned to it over the years. I’m an Anne Carson completist; I often return to the language of Eros the Bittersweet, Autobiography of Red, and Nox. I came to Elena Ferrante in my thirties, and Days of Abandonment and her Neapolitan novels gave me permission to fully explore dark-hearted women characters. Traces of these vastly different books can probably be found in how I write now.

What other professions have you worked in?

I’ve been a ghostwriter for nearly a decade, and before that, I was a litigator in a range of practice areas for almost eight years. Litigation served as a great opportunity to watch the many ways in which people wrong one another, and how all the people involved in a wrong feel about it, and the discrepancies between their self-narration and their presentation to others. I’ve also worked in graphic design, illustration, data entry, film festival programming, and childcare.

What did you want to be when you were young?

I never wanted to be anything but a fiction writer. Looking back on my own childhood desire, it seems like an outsized ambition. What did I know about what I was claiming for myself? But from the moment I learned to read, I spent a lot of time alone reading books out of necessity. Straightaway, it seemed to me there was nothing I would rather spend my time doing than making things up and putting words together in the right order. I knew I had to find some other way to make my way financially, but I kept writing at night and on weekends.

What inspired you to write this piece?

While working for a film festival a decade ago, we took a visiting French film critic to dinner at a Cuban restaurant. Over mojitos, he told our group the story of how the power had gone out during an outdoor film screening he hosted somewhere in Africa decades ago. He’d narrated the rest of the story for the audience without any pictures in the dark. That moment haunted me for several years. I thought about what it might be like to have been in the audience, having never viewed a movie before. It made me see cinema and technology differently, as forces inspiring wonder, rather than something commonplace and frequently disappointing. Later I learned that there used to be tent cinemas in Thanjavur, the part of Tamil Nadu my father is from. I wondered whether the story the film critic told could have happened in Thanjavur and began writing Tent Cinema.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

I’ve lived most of my life in the Bay Area. Living here is an undeniable influence on all my writing, even fiction set elsewhere. I also return again and again to the imaginary cities described in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, a battered copy of which I borrowed from one of my best friends in college and never returned. While writing "Tent Cinema," I was thinking about Thanjavur, about visiting my grandmother and great-grandmother when I was eight, and sitting on the floor eating, while outside it was lush and muddy from monsoon rains. We ate rice and other food from palm leaves, though my father advises me this was just to give my young self a sense of cultural traditions, not because anybody in my family regularly ate from palm leaves in the eighties.

Is there any specific music that aids you through the writing or editing process?

I listen to music to set an atmosphere specific to the story I’m telling while writing drafts. For the past two years, I’ve been listening to a lot of Nightmares on Wax, and also Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holliday to evoke romance and put me into an old-timey state of mind. During revision, I need complete silence.

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

I used to paint and make installation art but have since abandoned those pursuits because I couldn’t see a way forward with them. I knew I wanted to spend most of my time writing regardless of the outcome of that writing, regardless of whether other people liked it—writing was survival—but I felt paralyzing anxiety about making visual art and having people judge my risks in visual art as wanting. The older I get, the more I wish I’d retained music and songwriting, which were elemental childhood interests, but which came to seem like my sibling’s purview.

What are you working on currently?

I’m working on a novel whose character list includes Katran from "Tent Cinema." It is a family saga that spans more than seventy years and features a speculative memory machine.

What are you reading right now?

I always have multiple books cracked open to different ends. A book I’m reading for my own satisfaction is Meng Jin’s beautiful and haunting debut novel Little Gods.

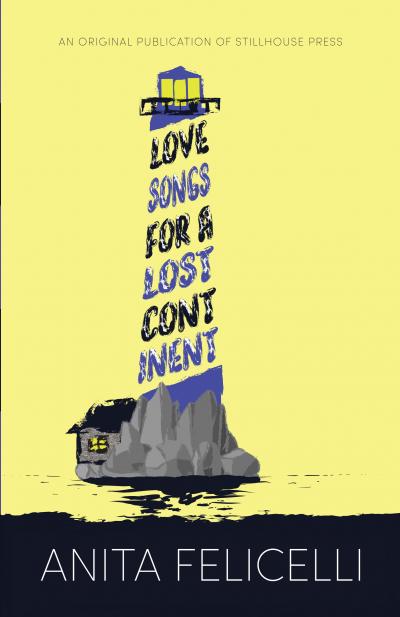

ANITA FELICELLI is the author of the novel Chimera, and the short story collection Love Songs for a Lost Continent. Her essays and criticism have appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle, Los Angeles Review of Books, Slate, Salon, Catapult, New York Times, and elsewhere. Love Songs for a Lost Continent won the 2016 Mary Roberts Rinehart award. She lives in the Bay Area.