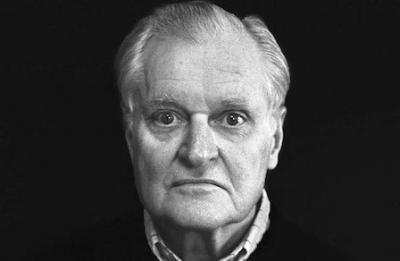

That Shining Golden Thread: An Appreciation of John Ashbery

- By Michael Thurston

It’s right there in the title of the New York Times obituary: John Ashbery’s work is not only “celebrated,” but it is also “challenging.” PBS calls the poems “enigmatic,” while for NPR they are “confounding.” The more knowing and admiring pieces by poets or critics (sometimes the same people) nuance the point, while still emphasizing difficulty. Mark Ford’s sympathetic and knowing obituary in the Guardian, for example, non-pejoratively describes Ashbery’s poems as “innovative” but also “unorthodox,” “disjunctive linguistic collages that defy paraphrase or explication.” Dan Chiasson, in the New Yorker online, describes the second phase of Ashbery’s career as “rather frantic and trippy.” While it is a thread that runs through the fabric of these retrospective summaries, the sheer sensory and intellectual pleasure offered by Ashbery in poem after poem over a career that lasted almost seventy years is too often subordinate, a complement to the keynote of obliquity and weirdness. It ought to be the shining golden thread around which all the rest are woven.

Many of us who love Ashbery’s poetry have a few go-to poems, the ones we recommend. It may be that these exemplify the common traits or the rewards of reading him, or it may be that these were our own gateways, the examples slipped to us on syllabi or in anthologies and by which we were then hooked, set to hunt down the harder stuff. One of mine is “Daffy Duck in Hollywood,” certainly part of the “frantic and trippy” period (it appears in his 1976 book, Houseboat Days). Here’s the opening:

Something strange is creeping across me.

La Celestina has only to warble the first few bars

Of “I Thought about You” or something mellow from

Amadigi di Gaula for everything—a mint condition can

Of Rumford’s Baking Powder, a celluloid earring, Speedy

Gonzales, the latest from Helen Topping Miller’s fertile

Escritoire, a sheaf of suggestive pix on greige, /

deckle-edged

Stock—to come clattering through the rainbow trellis

Where Pistachio Avenue rams the 2300 block of Highland

Fling Terrace.

Okay, let’s stipulate to oblique, weird, even frantic and trippy. But can we also talk about how much fun that is? A short, straightforward, single-line first sentence seems to establish a familiar lyric fiction, a first-person speaker who is reporting on some kind of subjective experience. We’re invited to identify with this familiar feeling. So far, so good. But then that second sentence, compound and complex, a catalog neatly packed between those dashes, the whole thing studded with proper nouns, images and diction from different registers jammed together so that the straightforwardness of the first sentence feels now like a feint. Who is La Celestina? What is Amadigi di Gaula? What’s with Helen Topping Miller’s writing, desk, and paper? On one level, it doesn’t matter. Knowing that La Celestina is a 1499 Spanish tragicomedy or that the title character is an aging prostitute, knowing that Amadigi di Gaula is an Italian opera that Handel composed in 1715, or that Helen Topping Miller was a twentieth-century American author of light romances and historical fiction does little to explain how these references fit together, and nothing at all to help a reader relate them to Rumford’s Baking Powder or Speedy Gonzales. On another level, having a Google window open to look these things up adds something to the sense of the poem as a cultural Cuisinart, a pastiche of high and low reference. But what’s really fun is to remember, as the next lines remind us, that this strange sentence is supposedly spoken by Daffy Duck, who name-checks his fellow Warner Brothers protagonist in the middle of the parenthetical catalog, and who later puns in a gleefully (and cartoonishly) self-referential way: “so déconfit are its lineaments,” “some quack phrenologist’s / Fern-clogged waiting room”). So try these lines on with Mel Blanc’s Daffy voice in your head:

That geranium glow

Over Anaheim’s had the riot act read to it by the

Etna-sized firecracker that exploded last minute into

A carte du Tendre in whose lower right-hand corner

(Hard by the jock-itch sand-trap that skirts

The asparagus patch of algolagnic nuits blanches) Amadis

Is cozening the Princesse de Clèves into a midnight /

micturition spree

On the Tamigi with the Wallets (Walt, Blossom, and little

Skeezix) on a lamé barge “borrowed” from Ollie

Of the Movies’ dread mistress of the robes.

What does any of that mean? Which is to say, what is the paraphraseable prose content we might patiently extract, as we would hope to extract a fortune on a slip of paper baked into a cookie or a message carefully folded into a complicated envelope? I have ideas about that, but really I don’t think they matter. Or if they do matter, they matter not nearly as much as the levels of play at which we are invited to engage. You can imagine a scene, as “unrealistic” as the Warner Brothers cartoon universe allows: a huge firework explodes at once over Anaheim (Disneyland, by the way) and into another kind of document, and in this illumination we see characters from French literature pissing in exotic locales along with figures from an American comic strip. At the same time, we can revel in the erotic echoes, whether the high-falutin’ pun in carte du Tendre or the double entendre of “skirts” or the locker room joke of phallic asparagus (set up by the locker room plague of jock-itch). And, more elementally still, just roll some of those phrases around in your mouth and enjoy the alliteration of “asparagus,” “algolagnic,” and “Amadis,” of “midnight micturition,” or of “barge” and “borrowed.”

I’ll admit that this may not be everybody’s cup of fur, but for readers who have taken any pleasure at all in the French Surrealism that has, since the 1920s, suffused our literary culture, this is a rollicking good time. Ashbery spent years living in France, and both before and after that sojourn he translated French poets, but I don’t want to put too much weight on this, as if the “key” to his work is to be found in the magic castles of Martory or Breton.

Collage, on the other hand, is a very useful way to think about the particular pleasures on offer in Ashbery’s work. If we consider that the principle in collage is precisely the juxtaposition in the compositional field of items drawn from diverse discourses, then the effects we notice in “Daffy Duck in Hollywood” make sense. We don’t expect a collage to deliver unified or coherent “meanings,” so much as to call attention to relationships (or possible relationships) among bits and pieces. In the mode of play that situates references to French culture in a Warner Brothers universe (familiar, too, from Ashbery’s “Farm Implements and Rutabagas in a Landscape,” a fantastic sestina featuring the cast of Popeye cartoons), we can see evidence of Ashbery’s friendship and collaboration with Joe Brainard, whose collages similarly draw on such popular cultural figures as Nancy and Sluggo, and of Ashbery’s familiarity with the collages of Jess Collins, the longtime companion of poet Robert Duncan. But we might also think of Joseph Cornell, and behind him Max Ernst and Kurt Schwitters. And with all of this in mind, it will come as no surprise that Ashbery had a whole second career as a collage artist himself, with wonderful shows of his artwork at the Tibor di Nagy gallery (under whose auspices his first chapbook had appeared even before W.H. Auden chose Some Trees for the Yale Younger Poets series).

As I mentioned, “Daffy Duck in Hollywood” is a poem I point to when people ask, as they sometimes do, what’s up with that Ashbery they’ve heard of. But I don’t want to limit the range of available pleasures to those especially obvious in that poem. There are numerous Ashbery voices and visions, and each offers modes of enjoyment all its own. When you’ve got a few spare hours, allow yourself to sink into the brilliant poetic prose of Three Poems. If you’ve only got a little while for philosophical conundra pleasingly put, check out “Paradoxes and Oxymorons.” For a wonderfully wandering take on Orpheus and Eurydice, read “Syringa,” and for a subtle, lyrical meditation on representation and the ways it is always warped, one can do worse than “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror.” But sometimes, the Ashbery I most want to sit with for a while, is the quietly estranging, sometimes slightly winsome, sad but never somber kind of poem that recurs throughout his career. A favorite example of this, a poem I reread often (I’ve got a copy that someone typed out and gave to me decades ago in the top drawer of my desk), is “The Young Prince and the Young Princess.” Ashbery removed this poem, which he likened in an interview to “the more watery surrealists like Follain,” from the manuscript of his second volume, The Tennis Court Oath, but I love it. The last two stanzas might nicely conclude this little valediction-not-without-mourning:

Night comes, but this time it is a different one.

Your feet scarcely seem to touch the grass

As you walk; you have confidence in me;

Moths bump my incandescent head.

And I hear the wind. And so it goes. Some day

We will wake up, having fallen in the night

From a high cliff into the white, precious sky.

You will say, “That is how we lived, you and I.”

MICHAEL THURSTON is the William R. Kenan, Jr., Professor of English Language and Literature at Smith College.