Massachusetts Reviews: Absent Altars

- By Elmira Elvazova

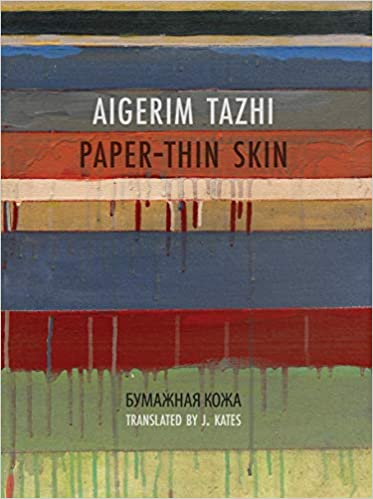

Paper-Thin Skin by Aigherim Tazhi, translated by J. Kates. Zephyr Press, 2019

For a debut poetry collection, Aigerim Tazhi’s Paper-Thin Skin is a work of stunning originality. Part of what makes this work so compelling is the way that it grapples with the mystery involved in the creative process, namely the act of turning “everyday life into a miracle,” which requires a kind of searching and tuning-in to all frequencies until one finds a clear signal. The poetic imagination, which alights at making connections between seemingly dissimilar things, is the focus of the book, revealed through the speaker’s interest in mitigating internal worlds with external realities.

I once had a poetry professor impress upon me the idea that to every poem there is an architecture and inside that architecture, a sacred space, the space of the title. To emphasize her point and give a visual representation to the metaphor, she took a poem of mine I left untitled and drew a circle at the top of the page, around the space where the title would have been. The circle contained nothing—it was an absent altar. Nowadays, when I encounter a poem without a title or a collection of untitled poems, I imagine absent altars floating in space, as much as one can imagine an absence. The carefully crafted, free-verse poems in “Paper-Thin Skin” are all untitled, to wondrous effect, they constellate together at a dizzying speed, in a remarkable unfolding of thought and language. The titular lines are grandstanding, acting not as a placeholder for a title, but dramatizing the reader’s entrance into the poem. Reading an opening line like “Probably God is like a dying person…” or “A violet sucks from a saucer yesterday’s sea filtered through the earth…” is not like surreptitiously opening a door so much as being swept inside by a strong wind.

There is, infrequently, beautiful anaphora in these poems, as effective in the English translation as I’m sure it is in the original Russian: “Who are you, unknown sculptor in a white coat? / Who are you, who stitched black wounds on the winter river…” and later, “I will go north this will be fair / I will leave my heart but only in pieces.” Alongside the anaphora, imagery that stuns by its strangeness and simplicity: “A crown woven into a nest without fledglings / pulls the vines to the leaden sky.”

The narrator gives us glimpses into others’ lives. All the people and creatures we encounter along the way, real or fictitious, are captured as if by a photographic snapshot, frame-by-frame. Quotidian scenes that portray domestic life in the country are interspersed with scenes of a surreal nature: “In a sandbox under the playground mushroom / a man-shapeshifter has fallen asleep, / half of him wolf.” We usually meet these fanciful characters in medias res, as though the narrator stumbled upon a scene that had been playing out, in the same way, for a long time and will repeat in perpetuity. This imparts onto the poems the tone of an absurdist-theatre play: “Look over there and up . . . / There’s an old man, surrounded by quiet and light. / For a long time he’s had a rabbit up his sleeve / And he calls for a stroll through heaven.” We can only imagine the pictures left in the darkroom.

Halfway through the collection, Tazhi writes: “I strain to listen for an imagined world: / one that absorbs music from the outside, / and will not preserve the borders / of an internal country,” but, she goes on to say, “something obstructs the oblivion of a dream.” What precisely can this be? What can we name this underpinning anxiety that “knocks in the night / rhythmically, like a god of radiators”? Indeed, the narrator’s preoccupying question seems to be: where do internal and external landscapes intersect, and how transparent is the imagined world?

In the collection’s opening poem, we meet a traveler “walking like a camel” in a desert oasis with “eyes of different colors, / hands carved from wood,” holding a violence inside himself, or the scar of an old injury: “a dead viper in his breast.” The unnamed traveler, written like a caricature of a monster, is envisioned as having “paper-thin skin translucent” beneath which “letters shine through the forehead.” What would the world be like if we could read another person’s thoughts in passing? Is mind-reading technology in our future? This monster is perhaps a prototype or a relic, an unwelcome reminder of the past. It evokes for me the anxiety of living in a dystopian surveillance state.

The performance of light figures prominently here as well. “Light” is realized as another character in the book—sentient, feeling, observing. “Light touches something cold to the body,” it “leafs through the outlines,” “transparent light withdraws into a cold garden,” the sun can “sketch signs on the skin,” or “throw lavish glares / marking out the brokenness of space.” This intimacy, the speaker’s connection to light, shadows, and darkness, adds a tenderness and depth of feeling to these spare poems as photographs, to the fleeting images of life.

Tazhi’s poetry is one of a reversal of roles, a depersonalized narrative, built from a heightened observational sense and attunement to the outer world that dramatizes the inner landscape, where phenomenal imagery accrues, where roles, sensations, and images are always changing, metamorphosing, as “the angle of the sun shifts.”

The book’s extended title is “Paper-Thin Skin (In the Grip of Strange Thoughts),” the parenthetical acting as an apt description for the collection as a whole. In her poetry, Tazhi confronts a certain uneasiness, an anxiety that is always bubbling underneath the surface. Though she speaks from a place of confinement, in the “grip” of strange thoughts, there is a candor and expansiveness to Tazhi’s poetic register, despite some of the heavy subject matter that permeates the reading, that lingers beyond the reading.

Elmira Elvazova is a poet currently living in Northampton, MA. She has a Masters in Fine Arts in Poetry from the University of Massachusetts MFA Program for Poets & Writers. Her work has appeared in Paperbark Literary Magazine, Big Bucks, Big Big Wednesday, and elsewhere.