A Toast to Eric Bentley

- By Jules Chametzky

It is Friday, August 7th, and I just finished reading in the New York Times the major, generous, and informative obituary of Eric Bentley, written largely by the late editor of the Times Book Review Christopher Lehmann-Haupt. It was deeply moving to me. For more than sixty years I knew Bentley and much of his major work, sixty plus years out of the 103 he spent on this earth.

In my last year in college, 1949-1950, I began to write plays, more or less successfully, that were produced at Brooklyn College in its Writers Workshop in the late afternoon, as well as a whopper of a production of a longer play staged in the evening, after my graduation, to a large public audience. That year I also read Bentley's first major book, The Playwright as Thinker, written when he was twenty-seven and still, in my opinion, the best work in English on theater and drama, with its focus on European dramatists, including groundbreaking work on Bertoldt Brecht. It had fateful consequences for me.

In the afternoons I had been happily teaching sixth graders in English in a Brooklyn yeshiva, and writing in the mornings. Then the Korean War broke out, so I thought I had better get into Graduate School, which might help towards a deferment in the draft, even if only for a short time. I applied to the University of Minnesota, where Bentley was then teaching, as was Robert Penn Warren, whose book All the King's Men about a Huey Long type of demagogue was then a hit novel and motion picture. I was accepted.

But, alas, both writers had departed by the time I got there in 1950-51, Bentley to Columbia, Warren to Yale. I was quite disappointed and almost left, but was saved and changed careers because of three great professors there—Henry Nash Smith, Leo Marx, and Mulford Sibley—who taught and inspired me. Ten years later, I did get to know Bentley and began a friendship that lasted.

The “breakthrough” in our relationship came shortly after I became one of the earliest founding editors of the Massachusetts Review. One pleasant task assigned was a trip to New York City with Joseph Langland, a poet and founder of the UMass MFA program, after we learned that Bentley had quit Columbia. We were trying to recruit him to become head of our young Comparative Literature Department. It didn't work out, but it did cause the resignation of the head of that department when he learned of our mission. He knew he didn't stand a chance against Eric!

No surprise that our mission was unsuccessful: Eric was firmly active in leftist, largely anti-war activities, in Manhattan; in any case, we did get to see him in his great apartment on Riverside Drive. Among its memorable features were a grand piano with a song sheet by Hans Eisler ready to be played, Bentley’s own haircut à la Brecht, and his refrigerator full of Polish potato vodka.

He was running the cabaret he started, with a wonderful name, taken from the territory between North and South Korea: DMZ (the Demilitarized Zone). Readings and lectures were served along with food and drinks. Eric complained that, after about twenty years of distinguished teaching there, much to Columbia's shame, they had taken away his office and some other privileges he thought he should be granted.

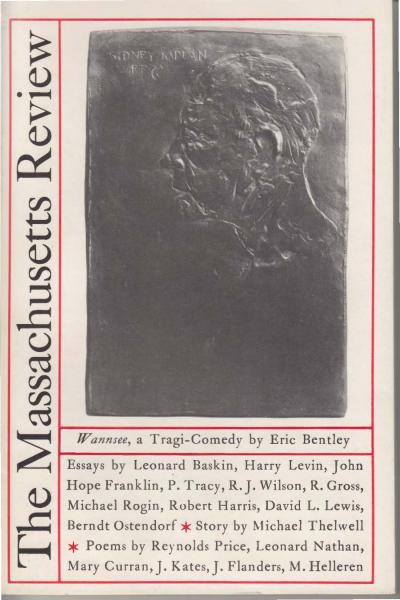

We did publish a long play of his, "Wannsee: A Tragi-Comedy," in the Massachusetts Review, and I did attend another play of his, "Expletive Deleted,"—taken entirely from the Nixon White House tapes and performed for a single night at the Theater of the Riverside Church, with Rip Torn as Nixon. Like Bentley's earlier "Are You Now or Have You Ever Been," which was based on the proceedings of the House UnAmerican Activities Committee, this was revolutionary theater, since you couldn't help feeling those people were insane as well as evil demagogues. The earlier play didn't get a good review in the Times, but I wrote a very favorable rebuttal article in a drama journal.

Then there was Eric's performance of the songs of Jacques Brel, in a strange theater near the Hudson River, shaped in a half-moon curve, with the performer in the middle and no way out but past him. He had produced a leaflet announcing the performance at the nearby MLA meeting, which I attended with Werner Sollors. Eric’s singing was very poor. So he lashed out at the audience, saying he knew they thought it was bad, “but don't forget,” he continued, “I am a better critic than any of you!” Who could disagree?

As Werner and I exited right, past the stage and his dressing room, we saw Eric in there with his Black male lover (there was also this side to his life, along with two marriages with women and several children). When I told him a short while later that we had been to his Brel evening, he asked why hadn't we dropped into his dressing room to say hello afterward. I had no reply then, but now regret that we hadn't “dropped by.” On one occasion in the early seventies, when I was about to go to Germany to teach at the Kennedy Institute in West Berlin, he asked me to deliver a letter to an East German dissident folk singer, Wolf Biermann—a kind of DDR Bob Dylan living in East Berlin. Biermann later was expelled from East Germany and lived in Hamburg, from which he once made a visit and performance at UMass. As asked, I dutifully delivered the letter to his roommate in a tenement in the East, the only “illegal” action in my many trips and semesters teaching in Germany. I imagine the Secret Police must have gotten wind of this malfeasance, but nothing dire ever happened to any of us—though I feel I earned Eric's respect—a smidgen of my respect for him. The last time we physically met was at his eightieth birthday party at a great bookshop in Manhattan, where at least one of his grandsons cavorted around as Eric spoke in his beguiling way.

I owe much of my intellectual life to you and your many fine books, Eric, but I most thank you for the taste of Polish potato vodka. I raise my glass to you. With love and gratitude, Jules Chametzky