10 Questions for Jennifer Sperry Steinorth

- By Edward Clifford

When one braids together

a horse

and a fence

it isn't pretty:

mangle of mane and wire, twisted legs

cedar splints. Once

on a hill

in a far country

I watched some horses across a dust road

—from "Range," Volume 61, Issue 2 (Summer 2020)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you wrote.

Hmmm. One piece, back in undergrad, I remember clearly. I was studying with Diane Wakoski; her workshop method was unusual. Each week we passed around copies of our new poems and read them aloud without comment, while she took notes. After, we watched as she arranged the poems from “best” to “worst”; then we workshopped in that order—“best” to “worst”. You never knew who was next, and if your poem was towards the bottom, you didn’t get workshopped. As a teacher, it is not a practice I would deploy, but as a student, I learned a lot!—though it was weeks before a poem of mine was workshopped— perhaps because of it.

So, this particular poem I submitted in my second semester studying with Diane. It was fall, our first assignment, and I’d written the poem over the summer. I fell in love that summer and wrote a heap. And so many drafts of this one poem! There was false translation—bits in French—an attempt to get at the madness of losing and finding oneself in another. I brought the poem in—nervy, but you know, trying to be detached— and lo! After the reading and the shuffling, mine was the first poem. And Diane said—I’ll never forget—“This is a perfect poem.” I was floored. In hind sight, I’m not sure exactly what she meant by “perfect poem”; I think she meant—it was a poem.

I’d like to say I learned what it took to write something worthwhile—the slow work of revision, the discomfort of revealing something terribly at stake—but really, it was just the first time I learned a lesson I keep needing to learn.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

This is a hard question to keep succinct! Okay—here are some contemporary writers that fly to mind.

C.D. Wright’s One With Others blew my top off right before I started grad school—which was late. I too grew up in the south; the vestiges of regional dialect and the formal play which sometimes does violence to those lyrics feel like home to me. Valerie Martinez’s Each and Her, is a gorgeous and haunting assemblage that also addresses systemic violence. Like One With Others it was published a decade ago and remains tragically prescient. Toni Morrison’s Beloved—which I first read in high school-- radically shaped my thinking about motherhood and otherness in ways I am still unpacking.

The critical and/or creative work of Jeanette Winterson, Mary Ruefle, Carl Phillips, Tony Hoagland, Jane Hirshfield, Adrienne Rich, Elaine Scarry, Layli Long Soldier, Anne Carson, Lorainne Neidecker, Albert Goldbarth, Heather McHugh, Ross Gay, and Solmaz Sharif haunts me.

And then there are writers who I have I had the great fortune of being in conversation with in life as well as on the page—the list is longer than I can share so I’ll name two particularly dear-- Fleda Brown and Maurice Manning.

What other professions have you worked in?

For upwards of 15 years I worked as a designer and licensed builder, running a construction firm dedicated to sustainability. That work—which I continue part time—has radically impacted my views of labor and justice and reinforced my appreciation for the relationship between the poem—that dwelling place—and the body.

My first love was dance—I was a serious ballet dancer until around 20, and later taught. I love teaching!—Thankfully so, as I’ve had some teaching assignments a bit outside my wheelhouse, namely visual and theatre arts. Currently, I’m an adjunct professor at Northwestern Community College teaching composition. I also offer independent writing workshops and mentorship whenever I can, as well as architectural design and consultation services.

What inspired you to write this piece?

I was at the Bear River Writers Conference, a marvelous retreat I’ve attended often, reunited with dear friends, but also grieving. I’d hiked alone to a bald rise a bit removed from main thoroughfares--a sort of unofficial meeting place--when some horses a-ways off noticed a fail in the split-rail fence and let themselves free. One came to me.

Is there any specific music that aids you through the writing or editing process?

I realized recently that I’m fairly high on the spectrum of aphantasia; I can’t visualize in my “mind’s eye” the way many can. I don’t see pictures when I read. But I am sensitive to soundscapes—I write towards a sound, hear words in my head when I read silently. Sometimes, in dreams, entire poems—or would-be poems--loop sonically through my head. So, though I love music—dance, my first love—if I am writing, reading or needing to think, I often find music too overwhelming and go without.

That said, I set an intention for the summer—to listen to more music and podcasts. In this time of isolation, to hear other voices seems particularly restorative, medicinal even.

Do you have any rituals or traditions that you do in order to write?

Nothing hard and fast—but the arrangement of my space is important to me. I’m not super tidy—but I need things arranged according to my aesthetic and utilitarian whims. If I am at a residency or such, my first task is often rearranging the furniture in my quarters. Or if I am to undertake a major project, revise a manuscript say, or push through something that demands many days or weeks of sustained effort, I’ll reorganize, clean and sometimes completely rearrange my space. It’s a kind of assessment of intention, what I might need—what books will support me, which can be cleared to make room for a new mess. There is also something about moving objects in space, orienting oneself toward an aesthetic sensibility—that lets my brain relax and start making connections in the work I seem to be procrastinating. To see what I need to see. Like cleaning the kitchen before making a big mess—which I also do!

Who typically gets the first read of your work?

It varies. I meet with some wonderful poets locally to commune and share work; that is a tremendous grace. And I have had a few very close relationships with other writers, who, for a time, were my “first reader”—each was a gift.

These days, I have many dear writer friends—more than I can keep up with—but few that I share work with and fewer still that would offer feedback. This is, at times, unsettling, particularly when I’m staring at bizarre creatures I’m not sure what to call. Then again, artistic relationships are delicate and take time. And I can be skittish. Also, it seems to me that in this political administration, relationships of every ilk have been under duress, for all kinds of reasons. But to this I’ll add that I am happily partnered—married for 20 years; though I share my work with my partner, he is not my first reader, and this too is a gift.

every ilk have been under duress, for all kinds of reasons. But to this I’ll add that I am happily partnered—married for 20 years; though I share my work with my partner, he is not my first reader, and this too is a gift.

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

Well, dance, as I mentioned, continues to haunt me—as in—my body is a house and dance still lives here. I could imagine some kind of performance work despite my aging body—celebrating it. I’ve long delighted in book arts and art books, studied some binding techniques, a little letterpress, exploring book-as-object and text-as-body. Body to body, my mother taught me to sew; those skills have yielded countless curtains, clothes, embroidered ditties. Sewing is not unlike making houses is not unlike stitching poems. But I would love to expand my visual art skills—and so do more in the making of book dwellings. And more collaborative work! Plays and puppet shows! Installations! Film! Oh, to stop time!

What are you working on currently?

I just completed my second book, an erasure of The Meaning of Art by Herbert Read, all 262 pages. From the voice of the male critic surveying art’s many male virtuosos, I excavate a first-person female lyric. It’s hybrid, a performative artifact, both poetry and visual art, and will be printed in full-color, hardback next year.

I’m still developing the language to talk about this work. I began in the summer of 2016 finding myself otherwise unable to speak, so enraged by the forces at play nationally, personally. Among other things, the book gives voice to the female object of art and of religion—that duplex of influence-- through a creative impulse that is inherently violent. In turns irreverent, ridiculous and melodramatic it moves from monotone obfuscation via white correction fluid to deployment of inks, scalpel, glue, needle and thread, applying “women’s arts” toward a kind of Frankensteined manifesto.

What are you reading right now?

Oh, not enough!—too many things, and too slowly. But I just finished Philip Metres exquisite Sand Opera—my first introduction to this poet--and now I want to read everything he’s written—which is a lot. Tommye Blount’s Fantasia For The Man In Blue is another bringing me to my knees—also Refusal by Jenny Molberg and Guera by Rebecca Gaydos. The Body in Pain—which I have been reading slowly, recursively, for at least 5 years—by Elaine Scarry is one I’m “finishing” right now, and I just repurchased A. Van Jordan’s M-A-C-N-O-L-I-A, my signed copy lost in a very sad postal accident, and am so excited to dive back in. Family Resemblance: An Anthology and Exploration of 8 Hybrid Literary Genres, The Book of Embraces by Eduardo Galeano and The Overstory by Richard Powers are others I am reading oh so slowly and with deep delight.

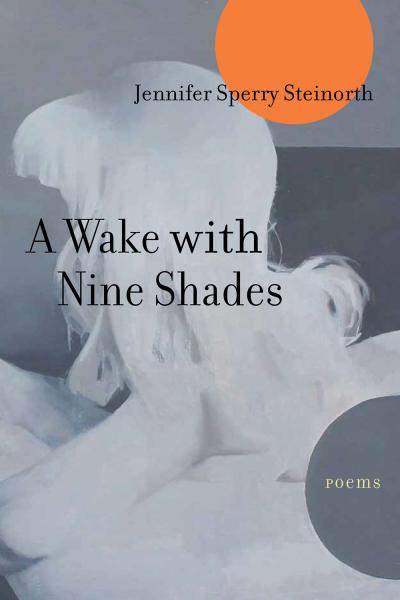

JENNIFER SPERRY STEINORTH is a poet, educator, interdisciplinary artist, and licensed builder. Her poetry has appeared in Alaska Quarterly, Beloit Poetry Journal, The Colorado Review, jubilat, Michigan Quarterly Review, Mid-American Review, New Ohio Review, Poetry Northwest, Quarterly West, and elsewhere. She has received grants from Vermont Studio Center, the Sewanee Writers Conference, and Warren Wilson College where she received her MFA in poetry. Her first full-length book, A Wake with Nine Shades, was published by Texas Review Press in autumn of 2019. A hybrid text of visual poetry/erasure is forthcoming from TRP, Spring of 2021.