Going Postal

- By Ward Schumaker

In 1968 I was living a half block from San Francisco’s Haight Street, I’d just lost my job, and though I didn’t consider myself a hippie, I was stoned twenty-four hours a day. My speech and the condition of my eyes made that obvious, so how was I going to support myself? Simple: go to Post Office. If you could pass the exam, no matter how you looked or acted, they had to hire you. To deal with folks like me, the administration had decided if you were visibly using drugs or an alcoholic, or exhibited mental problems, you’d be sent to work at the Fleet Post Office, the unit servicing the US war on Viet Nam. The workplace filled up with long-haired guys wearing funny glasses, girls who couldn’t stop twirling in circles, and people who talked to phantoms and shook uncontrollably. It became known as the Drug Post Office, and its night shift was considered the spookiest of all.

That’s where I ended up.

But even though I was using, I’d been raised in Nebraska, and Nebraskans have a work ethic which doesn’t disappear just because reality seems made of elastic and crazy mirrors. And so, on my first night when I was directed to unload a large truck, I jumped in the back and started rapidly, enthusiastically, throwing mail sacks down to the guys working on the dock. To be exact, I’d say they were waiting more than working. Unmindful of the hostile looks I was getting, I kept on throwing––until one of the guys jumped into the truck and warned: Work slower or we’re going to take  you out back and beat the shit out of you.

you out back and beat the shit out of you.

He looked like he meant it.

Over the next few weeks I learned that the postal employees (at the San Francisco’s Drug Post Office, at least) considered working diligently to be aiding and abetting the enemy—and the enemy was, of course, the US Government and its Viet Nam war. Better you should spend your time in slow motion. Slow-down was doing the right thing, fighting to move our country toward righteousness.

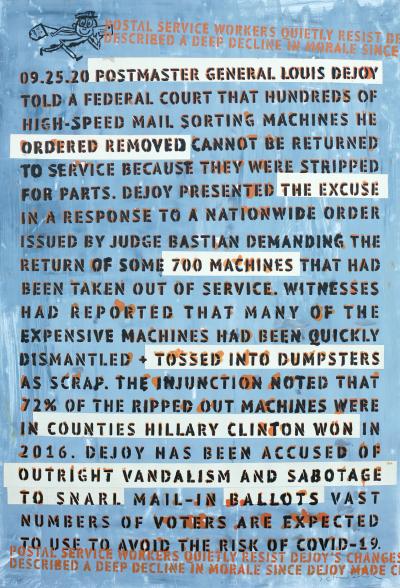

Years have passed and much has changed, but I was intrigued by recent articles recounting the resistance postal workers have been showing to the directives of the Trump-appointed Postmaster General Louis DeJoy. DeJoy—who has contributed millions to Republican causes and has continuing ties to his former company, a subcontractor with the Postal Service—has made a series of moves which support Trump’s attacks on mail-in voting and which many interpret as an attempt to undermine the 2020 election (expected to include more mail-in ballots than ever, due to the coronavirus epidemic). DeJoy’s actions include ending overtime, the locking or removal of hundreds of collection boxes, and removing sorting machines which have the capacity of sorting up to 30,000 mail items per day (it would take 30 employees their entire shifts to do the same work by hand). While a judge ordered DeJoy to undo these changes, DeJoy countered that it was impossible, given that the machines had been dismantled for spare parts.

Post office workers have told reporters that, to counter DeJoy’s orders, some had purposely drawn out the process of demolishing these machines until their supervisors gave up; others did an end run around their supervisors’ orders to leave election mail for last, instead sifting through the pile and delivering it first; and, because DeJoy’s move had also caused late delivery of prescriptions and social security checks, carriers were carefully culling the mail to give priority to

those items.

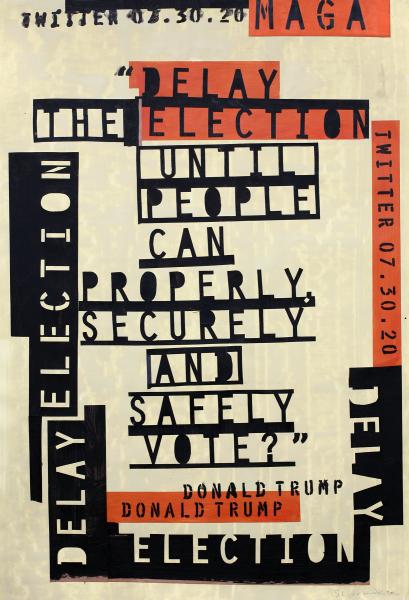

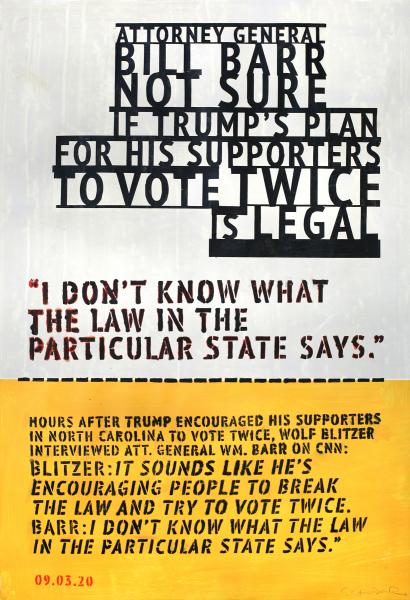

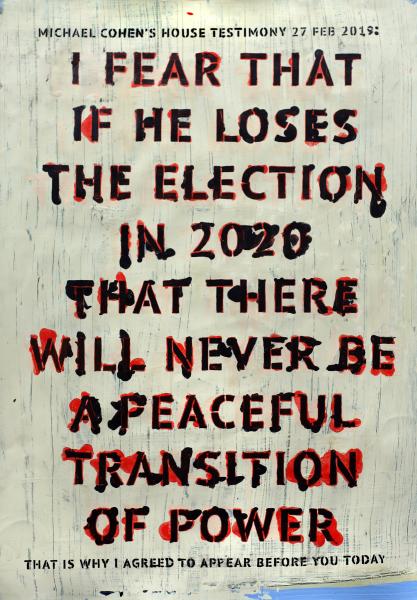

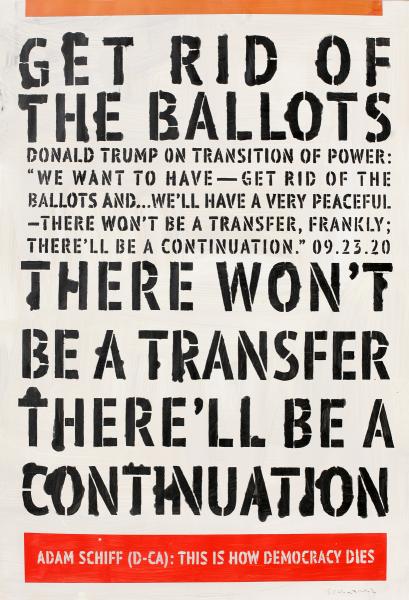

For me, given Trump’s talk of postponing this fall’s election and his suggestion for his supporters vote twice, the postal workers’ efforts sound both welcome and familiar: workers doing the right thing, fighting to move our country toward righteousness.

See Ward's other posts His Way with Words, Idolatry, Fiddling during the First 100,000, Kids-In-Cages, Trump Papers, The Pandemic, Lewis and Trump, and Decency.

WARD SCHUMAKER is an artist known in particular for his

hand-painted, one-of-a-kind books. An unintended and

fortuitous viewing of one—a collection of quotes from the

mouth of Donald Trump—resulted in the publication of

Hate Is What We Need, available from Chronicle Books.

Schumaker is represented by the Jack Fischer Gallery in

San Francisco.