10 Questions for Mohammad Shafiqul Islam

- By Edward Clifford

Hamid's wife has been in the hospital for two days.

At the Gynae ward of the Medical College. No indication for delivery yet. At times she feels a little pain—not so severe, though.

If asked, the nurse says that the doctor will wait a day more, otherwiseshe'll need an operation.

Operation!

—from"The Color of Death" by Selina Hossain, Translated by Mohammad Shafiqul Islam, Volume 61, Issue 3 (Fall 2020)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you translated.

I embarked on literary translation during the early years of 2000s, although translation literature and the practice of translation had fascinated me when I was a graduate student in English literature at the university. During those days, I used to pick a poem or a short story or two for translation that appeared interesting to me as well as was powerful in content. I can recall one such story by Bengali fiction writer Sumanta Aslam titled “Beast” that I ventured on translating right away after reading—later the story was published in the Eid Special Issue of Star Literature in 2007. Moreover, my early translations include renowned poet Rudra Muhammad Shahidullah’s seminal piece “The Smell of Corpses in the Air” and the most popular writer of Bengali literature Humayun Ahmed’s story “Eyes”.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

On the way to becoming what I am or what I am trying to be, many writers, poets, translators, and their works have had a tremendous influence on my writing. Although poetry is my favorite area, I also read great pieces of other genres that include classic, romantic, modern, and contemporary literatures. I still fondly remember how profoundly I enjoyed reading Homer, Sophocles, and Dante—in English translation, of course. At the university, we were taught Greek, Latin, and Russian classics in English translation. Among the romantics, John Keats influenced me immensely, and T. S. Eliot belongs to my all-time favorite poets. Besides, Charles Baudelaire, William Carlos Williams, Derek Walcott, Rabindranath Tagore, Kazi Nazrul Islam, Nissim Ezekiel, among others, have made me fall in love with poetry and more. I deeply admire Kaiser Haq, the leading English-language poet of Bangladesh, and his works. It is worthwhile to mention three phenomenal translators of Bangladesh: Kaiser Haq, Fakrul Alam, and Niaz Zaman. Above all, I love reading contemporary voices of literature, both poetry and fiction, from around the world.

What other professions have you worked in?

Since teaching as a profession has always been ideal to me, I have become, as a matter of fact, a professor of English literature, currently working at Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, Bangladesh. I usually teach poetry and literary translation, the areas of my interest, at the graduate level. Besides, I write poetry, the vocation that has subsequently turned into a passion. Thus writing poetry is part of my everyday life, my thought process, my love that I can never shy away from—writing poetry, therefore, is one of my devotional pursuits. As an integral part of my profession, I also carry out research in the areas of my expertise that include, among others, postcolonial literature, translation studies, and South Asian literature.

What drew you to write a translation of this piece in particular?

Selina Hossain, both popular and critically acclaimed, is in the front rank as a writer in Bengali literature. She has made an immense contribution to Bengali fiction, writing on a wide range of issues and themes. A keen observer of the contemporary reality of Bengal, she addresses the Partition 1947, the 1971 Liberation War, women’s plights and rights, and so on in her work. As an important writer, Hossain continues to draw attention of readers and then obviously translators. Among the female writers from Bangladesh who have received numerous awards and are translated into several languages including English, she has earned a secure position. Out of many of her stories, “The Color of Death” that appears in Massachusetts Review captivated me so intensely that I got down to translating it right away. The story must touch every reader as it addresses a very intricate reality of human life. Crisis, inner conflict, identity, grief, among others, revolve around “The Color of Death,” which is certainly a great and powerful story.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

I am not sure if any particular city or place, real or imagined, has influenced my writing widely, but place in general, of course, subscribes to the making of what I write, sometimes playing a part in remolding my thoughts and emotions. It is, however, undeniable that over and over I feel tempted to land in the city of Byzantium or the vast expanse of Keats’s nightingale. In essence, I am deeply rooted to my country, and topical incidents taking place in a particular time in a certain place, be it city or suburb, prompt me to write, and I try to respond to grief or wonder through lines of poetry. Rain or rivers flowing on quietly, hills or trees full of green leaves, flowers or orchards abounding in dewy grasses, butterflies or wood waiting to be turned into furniture are connected to space or place, and if they influence poets to create images, I certainly claim to have a flash of creative inspiration from them in perpetuum. Landscape, history, and culture of Bangladesh, my motherland which is metaphorically called Bengal of gold, has a magical influence on my writing.

Is there any specific music that aids you through the writing or editing process?

A great aficionado of music, I stand firm that music and poetry have a therapeutic effect on us, healing wounds, assuaging anxiety, and instilling in our minds a deeper understanding of life. I enjoy various kinds of music, depending on mood and milieu, but pick Tagore, Nazrul, and folk songs as my three absolute favorites. When I compose something on the computer or while travelling, I like to listen to some music. Soft songs run as the background music on my laptop most of the time when I carry on translating literary pieces. But if I need to absorb in analyzing some serious texts while writing research articles or penning poetry or editing any work including translations, I make sure the surroundings are peaceful and silence reigns.

Do you have any rituals or traditions that you do in order to write?

As a poet, translator, and academic, I feel a compelling need to engage, most of the time, in reading and writing, but all through my writing process, I do not find any rituals or traditions that may appeal to me or that I feel an urge to follow. But quiet of the early morning is always absorbing to me, which is why I see fit, if I do not sink off into sleep late at night, to write more during these illumining hours. One thing that I am alarmed about is writing under pressure, which may otherwise be called forced writing. I must, however, acknowledge that it does not take time to break the rules and ignore the routines that I sometimes map out and attempt to comply with for my creative work.

Who typically gets the first read of your work?

As soon as I finish writing a poem or translating a poem or a short story, I read it, most of the time, to Zaheen Epic and Zara Lyric—you can say they are often the first readers of my creative work—who also listen to me intently. Otherwise, I share my published work in different platforms, including social media, where many of my friends, poets, writers, and translators give me feedback. Sometimes, I feel elated by the words of inspiration extended by many unknown readers who write to me through emails or messages.

What are you working on currently?

At present, I am working on my third collection of poetry as well as a few translation projects. The projects that I am currently at work include, among others, a novel by Selina Hossain and Kazi Nazrul Islam’s letters. Besides, some other works are awaiting publication.

What are you reading right now?

I have a wide range of lists for reading, especially contemporary poetry and fiction. Typically, my everyday reading includes some poetry, and I sometimes choose poets randomly from various locations of the world. I have recently read Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic, Haruki Murakami’s Killing Commendatore, and Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day—all have certainly been a gripping read. Right now I am reading Matthew Zapruder’s Why Poetry, and from the long list of my subsequent reads, Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island, Derek Walcott’s White Egrets, and Adwaita Mallabarman’s A River Called Titash, translated by Kalpana Bardhan, are worth taking a look at.

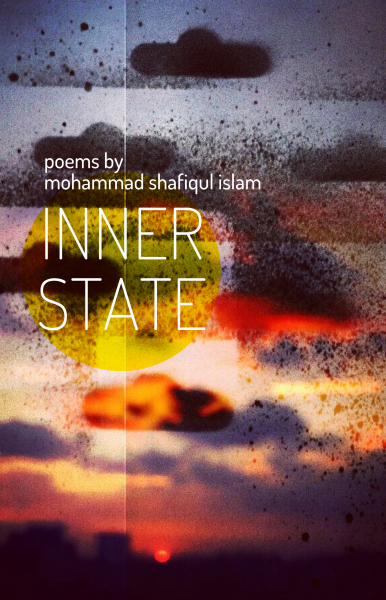

MOHAMMAD SHAFIQUL ISLAM, poetry editor of Reckoning, is the author of two poetry collections, most recently Inner State (Daily Star Books, 2020), and the translator of Humayun Ahmed: Selected Short Stories and Aphorisms of Humayun Azad. In February 2017, he was a poet-in-residence at the Anuvad Arts Festival, India, and his poetry and translations have appeared in Journal of Postcolonial Writing, Poem: International English Language Quarterly, Critical Survey, Stag Hill Literary Journal, SNReview, Reckoning, Dibur Literary Journal, Lunch Ticket, Bengal Lights, Armarolla, and elsewhere. His work has been anthologized in a number of books, including The Book of Dhaka: A City in Short Fiction, Of the Nation Born, Poems from the SAARC Region, and Monsoon Letters: Collection of Poems. Dr. Islam is Associate Professor of English at Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, Bangladesh.