10 Questions for Abigail Chabitnoy

- By Edward Clifford

A child walks the familiar road.

A body is found at the mile mark.

Still

they do not suspect foul play.

Still

they say she was Not Afraid.

—from "Girls Are Coming Out of the Water," Volume 61, Issue 4 (Winter 2020)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you wrote.

The first poem I remember writing was titled “Swimming Underwater”, and it was a concrete poem in the shape of a whirlpool. I must have been no older than 10 or so, and can’t remember anything else about it, nor did I really begin to seriously engage with poetry until perhaps 10 years later, aside from some awful melodramatic pieces in high school I believe my husband is thankfully the only one to ever have read. But apparently I’ve been obsessed with water for quite some time.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

As I feel storytelling is a prevalent interest and force in my work, though it might manifest itself in various ways, my influences reflect more than just poets. Tim Burton and Neil Gaiman were actually among my first influences that ignited a passion for storytelling and engagement with the bizarre. Anne Carson and Italo Calvino were among my first real literary influences that inspired me to pursue writing in college (specifically Autobiography of Red and Invisible Cities). Since then, I’ve developed my own voice while reading poets such as Jean Valentine, Alice Notley, Joan Kane, dg nanouk okpik, Anne Waldman, Eavan Boland—the list goes on. Most recently I’ve been reading HD, Adrienne Rich, and Audre Lord, as well as Tishani Doshi’s Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods. I’m interested in the ways these writers confront violence, the landscape, narratives we have inherited that both embrace and challenge hegemony. I often read fairytales and mythology, and have recently taken more of an interest in history after an entire academic upbringing of resistance to the rote memorization of names and dates. I also find I am influenced by graphic novels—Wicked + Divine, Monstress, Sandman, Saga—I’m interested in various approaches to stories and story structure, in work that weaves numerous threads.

What other professions have you worked in?

I’ve worked in the publishing industry, beginning as a proofreader at Scholastic Education Group when I lived outside New York City. Before that, immediately after college, I worked on an assembly line at a bookbinding factory, which despite its tedious nature and the lousy pay did allow my mind time to wander and really turn towards a more creative future track. I also worked a number of years as a research associate, event planner, media coordinator, and consultant for a consulting company that focuses on supporting indigenous self-determination efforts for several years before COVID. I left this work when the pandemic hit—it was a small family business dependent on government contracts and funding that became scarce at that time—but that has ultimately allowed me to focus more on my own writing as well as teaching, both in an MFA and community setting.

What did you want to be when you were young?

It seems a tired anecdote by now, but the first thing I clearly remember telling my dad I wanted to study when I grew up was “authorism.” When it came to choosing a college major, however, I had no idea what I wanted to be, and it seemed everyone was choosing English as a default—so I chose anthropology. I’ve always been interested in how different people tell stories and what those stories reveal about their worldviews and experiences. In hindsight, I would have enjoyed working in a museum.

What inspired you to write this piece?

This piece was in part a response to news of yet another indigenous girl going missing. (Quick Snapshot: As of 2016, there were 5,712 known incidents of missing and/or murdered indigenous women and girls, but only 116 cases logged into the DOJ database. Between 2005 and 2009, US attorneys declined to prosecute 67% of native community matters involving sexual abuse.) It was also in part a call to what I felt was the challenge in Doshi’s book—to engage, through poetry, in a process of transformation and resilience rather than languishing in a state of helplessness, fear, or victimization. Though I myself have not directly experienced sexual violence, as a woman in this society, I am impacted by the narrative of fear its acceptance perpetuates. The collection this poem is from takes to task narratives of violence against women and the landscape to find threads that continue to enable that violence as well as threads to mend it.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

I operate in a poetics of water. I am often haunted by the specific shades of the Alaskan Gulf waters that surround the Kodiak Archipelago and Aleutian Islands my family has been displaced from. The shapelessness and force of those waters, their give-and-take, their ability to join and separate, continue to influence my approach to poems in general and how I locate myself in any body of work.

Do you have any rituals or traditions that you do in order to write?

I need my desk. I typically write first drafts with pen and paper—and yes, a specific pen and specific paper/notebooks. Otherwise, when I find I’m not sure where to begin with writing, I read. Widely.

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

I would love to be able to work more visually. I’ve recently started working with linocut printmaking, but I wish I could do more mixed media painting or sculpting. I still have hopes of doing some type of graphic poetry piece with linocuts, but my skills are not there yet, and despite the time quarantining has afforded, I’m really not a great virtual learner. I’m a far too needy student!

What are you working on currently?

I’m possibly partially between works right now. I’ve just finished my second full collection and am waiting to hear from my editor. And I’m talking to a small press in Detroit about a limited release of a linocut illustrated chapbook I put together during a residency earlier this summer. I expect that project will develop into something fuller, but it hasn’t fully revealed its arch yet. I’m still interested in the stories we tell ourselves to survive, how to make something whole or wholly of fragments, how to reconcile our desired with our expected with our actual selves. . .the lines we carry with us.

What are you reading right now?

I’m revisiting some Alutiiq and ocean studies as I finalize my second manuscript, but on deck I have Evie Shockley, Jericho Brown, Brian Teare, and Jake Skeets. I have a bad habit of putting off those books I most want to read—because then I won’t have them to look forward to. Absurd, of course. There’s not enough time to read all the books worthy of being read. A New Year’s Resolution to overcome, perhaps.

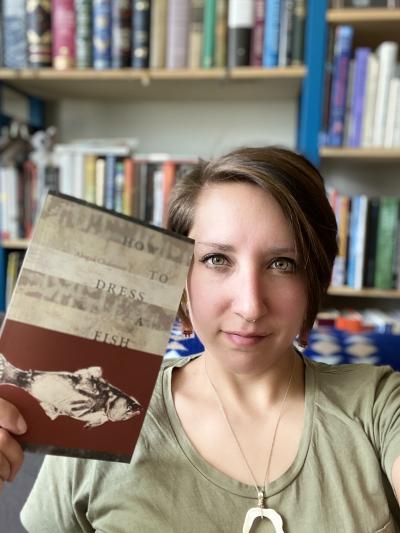

ABIGAIL CHABITNOY is the author of How to Dress a Fish (Wesleyan 2019), winner of the 2020 Colorado Book Award for Poetry and shortlisted in the international category of the 2020 Griffin Prize for Poetry. She was a 2016 Peripheral Poets fellow, and her poems have appeared in Hayden’s Ferry Review, Boston Review, Tin House, Gulf Coast, LitHub, and Red Ink, among others. Most recently, she was the recipient of the Witter Bynner Funded Native Poet Residency at Elsewhere Studios in Paonia, CO, and is a mentor for the Institute of American Indian Arts MFA in Creative Writing. She is a Koniag descendant and member of the Tangirnaq Native Village in Kodiak.