Wounded in Hatred, Part One

- By Joseph Keady

Following Fascism from Charlottesville to the Capitol

(Screenshots of Facebook posts, taken 12 August 2017. William Fears is currently serving a five-year prison sentence for choking his girlfriend. Alex McNabb is co-host of the neo-Nazi podcast The Daily Shoah.)

If you’ve never experienced it firsthand, let me assure you: the sight and sound of hundreds of men moving as a unit while loudly chanting the name of their chosen enemy is uniquely frightening. This is an obvious point, but it bears emphasizing, because it’s probably worse than you think. Recordings can echo the dread it induces, but they cannot reproduce it. Sports teams often parody it, but sports are rule-bound, and players’ theatrics frequently border on cartoonish. Armies don’t wear uniforms or practice marching in formations in the interest of efficiency: these are modes of social organization that give participants a feeling of collective power through unity, even as they intend to provoke a primal sense of anguish in their adversaries. A one-on-one confrontation can be intimidating, but a mass of hostile people operating as one coordinated, undifferentiated body transforms into both mammoth and wolf pack simultaneously, capable of either trampling or tearing from all sides.

When I arrived in Charlottesville, Virginia with two friends on the evening of August 11, 2017, I understood none of this. There was a lot still to learn. I was well acquainted with alt-right rhetoric and online aesthetics, but as we drove around looking for parking downtown, I was surprised (and almost disappointed) by how boring the small gangs of twenty year-olds looked, strutting around the neighborhood dressed as though they were out for a business jaunt across a golf course. This was “the new punk” we’d all heard so much about? In polo shirts and khaki pants? These were the people plastering the internet with glitchy, apocalyptic images of Wehrmacht soldiers and Greek statuary? Where was their edgy, ironic style that risked alienating and bewildering everyone over thirty? Darby Crash they were not. We would soon learn the depth of collective viciousness beneath their tediously bland packaging.

We were still strolling around, trying to get oriented, when text messages began accumulating about a fascist mob that had coalesced at the “nameless field.” Coded language? Some kind of Lynchian void? Or just miscommunication? Turns out there’s an actual place called Nameless Field, somewhere on the sprawling University of Virginia campus, but we didn’t have time to figure out where before the sound started littering our ears. What we heard was a droning incantation of the Nazi slogan "blood and soil" and the now-famous chant that alternated between “You will not replace us!” and “Jews will not replace us!”—asserting, in either case, the paranoid “Great Replacement” theory that has since motivated mass killings from Pittsburgh and El Paso to Christchurch, New Zealand and Halle, Germany. Even from far enough away that the words were hard to make out, the booming sound of a couple hundred voices growling in unison was enough to convey the message. As the racket grew louder, I half-kidded myself that it sounded like the end of the world. It wasn’t even the end of the first night.

Once we could hear them, it wasn’t long before we could see the trail of fire through the row of trees lining the edge of campus. The use of kitschy, bamboo torches—the kind you get for cheap alongside the bug zappers and plastic tablecloths in the housewares department—was a choice, and it served primarily as passive aggressive cover (“chill out, it was just a joke!”). There should be no doubt, however, that the marchers were fully aware of the torchlit lineage they were placing themselves in, mostly notably the Klan and the Nazi Party, as well as the contemporaries they were in solidarity with, like Greece’s neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn.

The students and locals who showed up on campus to confront them were badly outnumbered. A chat group of antifascist organizers quickly grew feverish with messages declaring that our side was surrounded and being doused with lighter fluid, then struck with lit torches. I suspected at the time—and later confirmed—that an old friend who I know as Uncle Frank was among them. I’d known him for something approaching twenty years at that point. He is a walking encyclopedia of film, history, and political theory as well as a deeply generous and humble spirit. He and I hadn’t been in regular contact in quite a while, but he is very dear to me and I owe him a great deal. What do you do when someone you care about is in the center of a raging mob? That night, I waited a few hundred feet away in anticipation of a longer, harder day starting the following morning. It was the least bad option available.

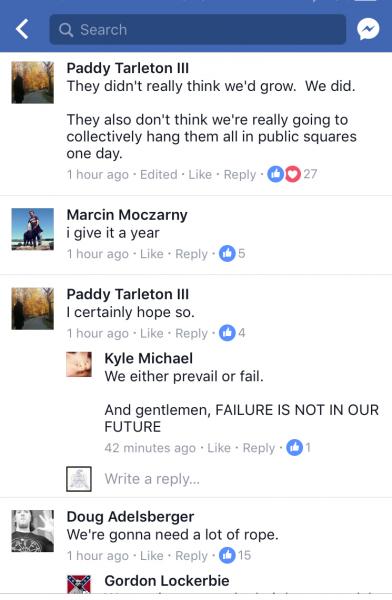

(Screenshot of Facebook post, taken 12 August 2017. Paddy Tarleton is a neo-Nazi folksinger. The "III" isn't a indication of who he was named after, it's a way of creating multiple FB accounts after previous suspensions from the platform.)

After fifteen minutes or so, the attack on campus ended, amid flashing police lights and claims that the attackers wanted to stay out of trouble and save their energy for the next day. Jason Kessler, the lead organizer of the Unite the Right rally, a former Obama supporter and Occupy participant (and one of the very few locals involved in planning that weekend’s events), walked right past me, flanked by four or five goons in matching blazers. I was close enough to trip him and, if I was lucky, maybe it would’ve cost him a few teeth. If it had, there was a very good chance it would have cost me several of mine as well. Might’ve been a worthwhile trade, but as I thought it over the opportunity passed me by.

The second day was not better than the first.

As an out-of-shape, middle-aged white guy, getting into fist fights with a mob of Hitler Youth twenty years younger than me did not seem like the best use of my talents. On the other hand, passing among them without calling attention to myself was pretty well within my range. So I decided that my role on August 12 would consist largely of sticking close to these brave Crusaders: blending in as best I could, taking lots of photos and video, and reporting out to other antifascist organizers whenever it seemed like anything important might be in the works.

As you may recall, the impetus for the rally that day was a city council member’s effort to have a statue of Robert E. Lee removed from a prominent location downtown in Emancipation Park, formerly Lee Park. The park covered one square city block, and the police had divided it up using metal barricades, rendering the northern half off limits while separating the southeast quadrant from the southwest with an empty, fenced-off corridor in between, a seven foot-wide no man’s land. Shields and helmets had become fairly common at far right events—ever since the previous spring, when images of Kyle “Based Stickman” Chapman, equipped with a shield, a helmet, and a long wooden rod at a protest in Berkeley, California, had inspired countless aspiring stormtroopers to follow his example. In Charlottesville, some of the better organized Nazis set up a shield wall—an array of shield-bearing thugs standing shoulder-to-shoulder—that blocked the entrance to the southwest section of Emancipation Park to anyone who couldn’t name an organization they were affiliated with, so I entered from the southeast, which was just a disorganized mob scene.

(Shield Wall breaking up. James Alex Fields, who would murder Heather Heyer later that day, is seen in 3/4 view, third from the left, in tinted glasses.)

Once inside, the universal irritation at the way the park had been divided was the first thing that struck me. Contrary to the myth that the current wave of far-right madness in the US is driven by working-class economic anxiety, these were up-and-coming, junior executive despots, and it was clear they were not used to being denied anything. The second thing I noticed was a small group of liberal, churchy folk singers who, for some reason, had decided that their act of charity for the day would involve hauling bottled water into the park for distribution. In their quest to save a horde of screaming Nazis from dehydration, of course, they also handed them a few cases of projectiles to lob at the antifascists, from a higher elevation inside. Who could’ve seen that coming?

The chaotic, volatile atmosphere on the edges of the park that morning is hardly news anymore, although the TV crews couldn’t convey the haze of pepper spray in the air (and we hadn’t yet transitioned into the era of bear mace and wasp spray—more on that later). There were a few cops around, but they mostly kept to the periphery and did nothing at all to keep people from beating each other. None of them were in the park itself, and it didn’t take long for the fascist horde to knock over the barriers separating southeast from southwest. I can't say for sure, but that may have been the trigger for the police to declare the event permit revoked, because shortly afterwards they finally appeared in numbers and ordered the park cleared.

(Leaving Emancipation Park, left, a neo-Nazi thug and, right, Daniel Borden, convicted of malicious wounding in the assault on DeAndre Harris later that day.)

The organizers had no real contingency plan, and the police certainly had no idea how to manage the warring factions; in short order, the fascist side split into at least two large groups that set off wandering in opposite directions. I stuck with a mob of a few hundred that plodded north for twenty minutes to McIntire Park. A number of these courageous, would-be conquistadors stopped along the way to have their picture taken with former KKK “grand wizard” David Duke, and somewhere en route, alt-right poster boy Richard Spencer pulled up in a car and jumped out for a moment to shake hands, as if he were running for office. (The crowd gave him mixed reviews.) Shortly after that, rented vans started turning up to ferry these intrepid Spartan warriors beyond the city limits—rumors (which turned out to be correct) had spread that a state of emergency was going to be declared.

After reaching McIntire Park, text messages began circulating calling for antifascist support in a neighborhood about a half-hour walk away. For a short while those calls seemed urgent, but soon the threat seemed to dissipate. Where I was, the courageous Defenders of Western Civilization were increasingly being spirited away to their undisclosed location outside Charlottesville. After a little while, there was no point in sticking around, so I headed back downtown.

By the time I got to Water Street, something was clearly wrong. My first guess, which seems absurd in retrospect, was that people were suffering from heatstroke. Some people were using signs and banners to give shade to other people who were on the ground. There were ambulances. Friends texted from hundreds of miles away, asking if I was alright. They were clearly better informed than I was. I didn’t want to ask anyone on-site what had happened. I was still dressed to be inconspicuous among hordes of screeching fascists, so striking up a conversation seemed ill-advised.

A group of armed militia members had turned up in a predominantly Black neighborhood. Local residents had requested support to protect the people who were living there, but by the time a large group of antifascists arrived, locals had already convinced the militia people to leave. People from the neighborhood then asked that the antifascist group not linger, given that their presence risked drawing police attention, so they left and sent out word that support was no longer needed. This contingent ran into another group of antifascists downtown, and they began marching together through the commercial district, in celebration of what felt like a major win over the vanquished fascists, who had fled the city.

There’s something all too appropriate about the fact that the weapon of choice that afternoon was a car, the epitome of consumer culture and an isolated bubble that turns every driver into a little autocrat. We Americans spend a lot of time in cars, often furiously contesting other drivers for a few precious feet of space on our way to or from work, where most of us instantly transform into the subjects of some other petty autocrat. Cars have a way of creating a hard border between the world within and the world without—and that applies even when the driver doesn’t have a head full of dehumanizing, genocidal ideology.

I first heard of cars being used to threaten or even attack protesters during the run-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, at a time when outsized trucks and nationalistic mania were, let’s say, all the rage. The post-9/11 era had rekindled the fading paranoia of the Cold War years and would eventually turn a lot of young people into battle-hardened veterans. Some of those well-trained, often traumatized fighters would come back to the US and take leading positions in a latter-day fascist movement that embraced a markedly anti-Semitic rhetoric of “anti-globalism” and an internally contradictory sense of anti-modernity. There is no shortage of irony that such a movement would adopt as a hero a twenty-year-old who, one day in Charlottesville, turned a machine produced through complicated, exploitative global supply chains against the raw flesh and bone of his adversaries. By the official count, one person died and nineteen survived with serious bodily harm. Dozens more were on-site, many of them traumatized.

(The Charlottesville car attack, photographed by Ryan Kelly for the Daily Progress.)

Trump’s electoral defeat is a welcome change, but we shouldn’t kid ourselves that it will undo the real or metaphorical wounds of this era. From one perspective, the origin of the current crisis goes back to Nixon and Goldwater’s “Southern strategy” and Pat Buchanan’s culture war. From a longer view, of course, it goes all the way to 1492. Fixing all that will require a lot of honesty and humility on the part of people who have historically been resistant to both. From the look of recent events in Washington, DC, and the eagerness with which many people anticipate a return to “normal,” this country may not be ready yet.

Joseph Keady is co-founder of the Just Words Translators and Interpreters Cooperative and a member of the editorial collective for Barricade: A Journal of Antifascism & Translation.