10 Questions for Suphil Lee Park

- By Marissa Perez

Do you hunger too? Rivers barging inland

fade shorelines

with the weight they have

carried.

—from "Gill" by Suphil Park, Volume 62, Issue 1 (Spring 2021)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you wrote.

A series of singsongy part-quartets about an abandoned bicycle that I jotted down in a music composition notebook that could have been, and might have worked better as, a simple haiku.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

I tend to read senselessly and impulsively, and am quick to relent what I’ve read to my awful long-term memory, so I always find it difficult to extrapolate which individual writers or particular work might have contributed to my own aesthetics. But no one’s ever stunned me more than Virginia Woolf did when I first read To the Lighthouse. She was the first to make me realize that writing can be both recklessly liberating and breathlessly probing at the same time, and I don’t think I’ve ever been so entirely caught off guard as a reader since. In a way, she shook me awake to the sheer material presence of language, so material that it feels organic and ironically, almost ethereal.

What other professions have you worked in?

I was a college instructor, tried out different roles at a micropress, and had a brief stint as an English tutor in a foriegn country. I also worked in procurement at an international trade agency which I soon realized was a fancy way of phrasing tons of emails and even more documents. Right now, I’m a literary agent at Barbara J. Zitwer Agency that has represented many prize-winning writers such as Han Kang, author of The Vegetarian, and Kyung-sook Shin, author of the NYT bestseller Please Look After Mother, and that specializes in traditionally underrepresented voices and international promotion. Way, way back, I’d say I was a magnolia culler, one of many millions of stamp collectors, and once, a desert town gatekeeper in one eerily recurring dream.

What did you want to be when you were young?

An array of eccentric or very traditional occupations with no end in sight, actually. As a little kid, I was in the habit of flitting from one infatuation to another. After my first dance recital at four, I announced to my entire family I want to become a ballerina, which became old news as soon as I found myself absolutely mesmerized by adventure stories such as Two Years’ Vacation and Robinson Crusoe, and decided to be an explorer, without a single idea what that occupation would really entail. Then followed the phases of my infatuation with zookeeping, open abdomen operations, myths and folklores, silkworms, mudflats, and so on, but not in this particular order. Eventually, I realized that through all those phases, one thing has been constant; no matter what captivated me for the time being, I was always exploring that interest in forms of writing, as a reader, and later, as a creative writer myself, even when the primary language of the country of my residence changed. It became pretty obvious by that point that writing is what will anchor my life, whatever I end up doing for a living.

What inspired you to write this piece?

At first, it was my rumination over the verb “have,” and various acts and modes of “having.” I find it kind of hilarious that this verb that means “to own” is also an important auxiliary verb to indicate tense, fleeting in nature. And to be auxiliary is to be extra, which is to say, unstable and fleeting as well. A state of having something, or someone, seems to be always just as temporary. Even life itself--as we “have” only so much time. It’s as if whatever we have in life is essentially a rental. Then why do some customs and traditions—the old ways of thinking—that we “have” to observe persist so? Coming from a country of countless have-to’s, one where I also often felt I had very little right, I dwelled on this idea of “having” and how it shaped the culture of my motherland. Especially how post-war Korea was still under the influence of an unofficial yet overarching caste system, or an illusion of it, while it became possible for virtually anyone to climb the social ladder—all of which led to a culture of steep competition, fitting in and getting ahead at all costs, jealousy, casual hyper-criticism, and obsession with ranks and grades. And I often wonder if the side effects of the last century might have also engendered the Korean culture of often irrationally possessive and overbearing parenthood--one seemingly led by notorious tiger moms. Supposedly freer, my home country in the last decades seems to have goaded its people into a crazed tunnel-vision life to “have” more. Specifically for women, to finally “have” everything through their children, because in theory, these women themselves should have been able to achieve everything they desired in this freer world but most likely couldn’t. Motherhood, though an invented concept as much as anything, is surely in part a natural instinct. But it seems it’s usually not so pure an instinct and more often than not laced with other, more complex and socialized desires.

Of course, this underlying desire to live a more ideal life, or to re-live by proxy, through one’s children, seems all too familiar. To equate having children and having second chances. But it’s especially interesting when you consider how South Korea, despite the drastic cultural and economic changes over the last decades, has been incredibly slow in catching up on understanding women’s reproductive rights. This particular aspect of Korean culture has been on my mind while working on this poem that took me months to really finish. So the Hudson was a perfect place to open the poem, the river off which the city of want and rat race has thrived. Because, what makes the river so glorious yet so unsightly is that want thrumming through it—to have more—which seems to be in perpetual contradiction of how much of the city, really, has so very little. A city of rentals, of borrowed time. But also a city where I didn’t necessarily feel safer, but most certainly freer. And the traditional Buddhist rite for the dead, 49 days of grieving, which I know some extremely conservative Korean families still respect, seemed like an appropriate chanting to echo throughout this poem, as my mind kept hovering over how the old traditions—especially those in honor of dead ancestors—still haunt the country, and how most of those have unfortunately usurped women and depended entirely on their unappreciated labor to date. I think as a young democratic country, but with centuries after centuries of rich culture and history, Korea is in such a complicated and delicate place today—and everything seems to be a balancing act between preservation of conventional values and a much-needed, more relevant perspective. And there’s undoubtedly beauty in both. I think in the end, it all comes down to figuring out what to prioritize, what compromise to make, and what to really “have” as lasting, truly important part of us, just as in that legend where the military strategist Gongming, in place of then-prevalent human sacrifice, invented dumplings so as not to shed innocent blood. It all comes down to how much of what we have really sustains us in essential ways. The rest might be better left to shift around that core of our being as they should. The rest might soon become vestigial after all. And for me, personally, it all comes down to what we all have in common, regardless of language, race, sex, culture, or any other circumstances that might define each of us differently—a simplest form of possibility sired and conceived from which all of us come, a state of pre-sex, and pre-human blood and flesh marked by its fast-disappearing gill. And how fascinating to realize understanding so much difference in us can only come from understanding this sameness.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

Ever since I moved to America, Manhattan has always been an important backdrop to my work, just as is the general impression of Korea I already had when I left the country just one year shy of eighteen. Since New York City is where I really got to start my immigrant life, it’s become kind of a thumbprint of what constitutes America to me, but the more pastoral elements in my writing come from my small-village experience before immigration. Some dreamscapes—battlefield, apocalyptic ruins, arid landscape—also translated into my poems, a few of which I actually started writing in dreams, and woke up to jot down the first few lines in a rush before they evaporated from memory.

Do you have any rituals or traditions that you do in order to write?

Not rituals, per se, but I always make sure to give myself enough time to grow out of a writer’s block, rather than forcefully write my way through it. When it comes to a writing slump, strategies can be countless depending on what kind of writer, what kind of person you are, of course. But it happens that my sole driving force for writing has always been the joy it brings to me, and how absolutely immersed I can get in this simple act of putting words on the pages, needing not much else for a long, long while. In a way, writing has been the best means for me to deal with life and this world from a safe, often enlightening distance, and with a sense of humor. In the middle of a dry spell, I try to accept that life does call for “else,” and sometimes I just have to let all the else’s in the world take over and run their course, so they’ll slowly give way to my good writing days again, as they always seem to do. Apart from that, solitude is the single most important tradition I’ve observed in all of my writing years. That, and conditional silence. Only when I’m alone and somewhat removed from the rest of the world do I feel I become an honest witness in regard to myself and the world, where I think my writing really begins.

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

I’ve always been drawn to visual art, especially those that can’t be reproduced, or, should I put it this way, those that will lose value upon reproduction—acrylic paintings, Asian ink paintings, and general hand-crafted mix-media art. Had I had more time and been more talented, or had I not been so predominantly fascinated with all kinds of writing, I would have probably ventured more in that terrain and worked on honing my visual art skills. I feel besides the obvious, what sets this type of visual art apart from other art forms is its inevitable susceptibility to destruction caused by its attachment to a specific “birthplace.” A painting destroyed is forever lost. A single authentic physical presence. A single original with a single lifetime. That kind of artwork best reflects what I consider the condition of human existence, self inseparable from its container. This type of artwork, unlike music, cannot be reinterpreted and reinvented by different artists without losing its identity. It cannot, unlike literature, be translated or mass-produced into different editions without being labelled 'fake.' No matter whose fingers ran the keyboards, no matter who recorded it, Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata would always remain Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata. Joyce’s Ulysses, no matter which publisher published it in whichever language, would always be Joyce’s Ulysses. But none other than Da Vinci can beget Da Vinci's Mona Lisa. Mona Lisa, no matter how much time elapses, no matter who comes to own the actual painting, will always belong to its sole creator, Da Vinci; this relationship will never change, even after the painting itself gets destroyed beyond repairs and only its name remains. In that sense, this kind of artwork has a singular, inimitable identity that is eternally contingent on its creator and its birthplace: demanding, real, almost human. The kind that is defined by and defines you. I often wonder what else exists so separately from and beyond yourself but will always exist as yours alone.

What are you working on currently?

I’ve been adding flesh to the backbone of my second poetry collection, and also working my way through the gradually more mysterious task of putting together a collection of short stories. A novel or two have been also brewing on the back burner of my brain for some time, so I’m hoping I’ll be able to get started on one soon.

What are you reading right now?

A lot of Korean fiction for work of late. And I happen to have just come across one of the most exciting high-concept literary fiction titles I’ve ever had the pleasure to read. It’s about a gender-bending, human-eating alien who struggles with gendered ways of life on the Earth and with the concept of justifiable consumption. A strikingly distinct new voice, for sure, with some great unsentimental insights and metaphors about what it means to live in our still largely binary world. It cuts right through to the heart of the matters, and its unflinching descriptions of the gory details of one severely alienated life feel more true than most realist fiction. I’ve also recently finished reading Great Exodus, Great Wall, Great Party by Chessy Normile, which I think is one of the most impressive, originally brainy debut poetry collections I’ve read in years.

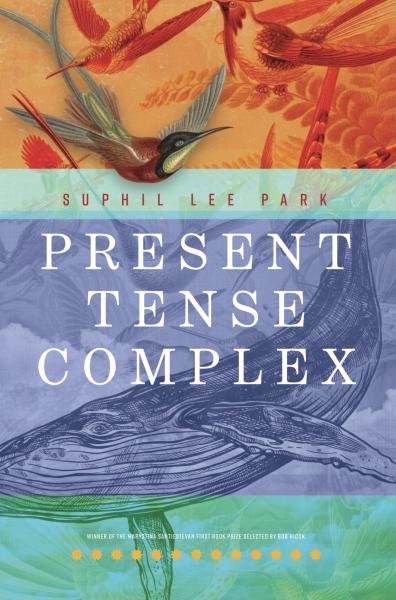

SUPHIL LEE PARK is a bilingual writer who grew up in South Korea. She holds a BA in English from NYU and an MFA in poetry from the University of Texas at Austin. Her poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Colorado Review, Denver Quarterly, Ploughshares, Quarterly West, and The Missouri Review, among many others. Her fiction received an honorable mention in the 2020 Force Majeure Contest and is forthcoming in J Journal, Storm Cellar, and The Iowa Review.