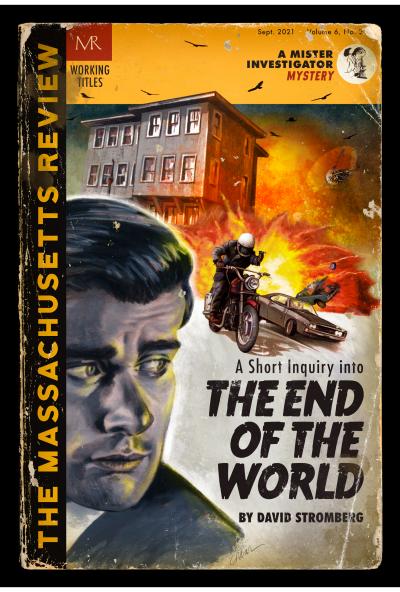

A Short Inquiry into the End of the World (Working Title 6.2)

- By David Stromberg

It looked like a regular day—all business as usual—but I knew that the world had come to an end. People went about their business as if nothing had happened. And I, too, did all the same things. I woke up in the same bed, went into the same shower, used the same soap. But I knew it was the end of days. And that, to understand how we got here, I had no choice but to investigate.

With everything destroyed, I couldn’t go outside, so I sat down at my desk and began with the only resource I had: my library. And since my only clue was the date of the apocalypse, September 11, 2021, I began by looking in the rubble of Art Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers.

I’d been in the audience, as a young gumshoe, when Spiegelman came to our college to speak about his comic series on 9/11, which had been summarily rejected by most mainstream media. It’s true, the Germans published it in Europe, and the Forward put it on its pages in America, but there was some basis for thinking about a coverup. Someone didn’t want Art Spiegelman’s comics to be read. The question was, what ideas did they want to suppress, and how were they connected to the end of the world?

I leafed through the book, which was no easy thing, considering its size. At first I didn’t find much that spoke to the current crisis. Sure, Spiegelman had covered all the pedestrian concerns about civil liberties during a time of war, and the existential confusion of feeling like you were threatened by bad actors within your own nation’s government no less than by foreign terrorists. And I could sympathize with many of his points about the post-traumatic state of the culture after the fall of the Twin Towers. But it was one thing to talk about news binges and conspiracy theories, and another to find the cause of the world’s destruction.

But then I started noticing certain phrases that put me more squarely on a path forward. “Nothin’ like the end of the world,” wrote Spiegelman, “to help bring folks together.” And in another place, speaking of a group of sleeping cartoons, he asks, “How can they be so complacent? . . . I know they’re on meds of some kind, but don’t they know the world is ending???” It seemed he was on to something, but it wasn’t yet clear what. And then, on the last page, I came to the first concrete statement that put me on the path to the source of the end of days.

“September 11, 2001, was a memento mori,” he wrote, “an end to Civilization as We Knew It.” This sentiment was accompanied by a hyperspecific focus on national politics, along with Spiegelman’s musings on the demographic differences tearing up America’s social fabric. I didn’t necessarily disagree with him. But I was investigating the end of the world, not just the acrimony of political history—and that was when I realized that his last idea was the opening shot to a question that put all convictions in doubt.

Spiegelman had referred to September 11 as “the end of Civilization as We Knew It.” What kind of civilization did we actually know? How were we—the biological or spiritual children of the Holocaust—even able to use a word like civilization? From where I sat, Civilization as We Knew It was not much of a civilization at all. What did we really know about it, and if civilization wasn’t what we thought it was, what had actually come to an end on September 11, 2001? . . .

Buy now from Amazon, Kobo, and Weightless Books.