Order a copy now

Order a copy now

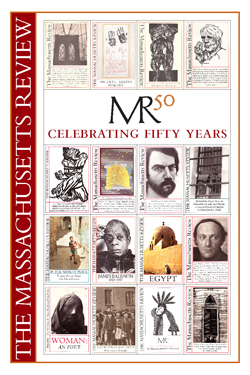

Volume 50, Issue 1 & 2

WHO HASN'T DREAMED of starting a magazine? To coagulate one's tastes and opinions into a satisfying rectangle? To join other dashing, jet-set ting editors in trenchcoats and sunglasses, dictating literary history against the back wall of a cafe? To be a ninja (or at any rate a plowhorse) for Beauty, Justice, Imagination, and Art? To marshal one's brilliant friends into battal ions, maybe even a Movement? To find tomorrow's National Book Award winners like silver coins in the dew?

So what if the lifespan of a magazine is less than a decade? People still get married, don't they? Now and then a marriage or a magazine endures, as this journal has, for an improbably long time.

What passed through our founders' minds? One of them, editor emeritus Jules Chametzky, recalls that the Massachusetts Review was the brainchild of faculty in the humanities—notably David Clark and Sid Kaplan of English, and Fred "Fritz" Ellert of German. To combat isolation in what was then a very rural, half-built campus, they sought to open a line of interchange with the greater world. Ultimately, the early editors reached out to neighbors at Mount Holyoke, Amherst, and Smith colleges (Hampshire College wasn't born till Volume 11), many of whom came in time to play critical roles in the birth and growth of the magazine. Jules cites the recruiting of Leonard Baskin, then at Smith College, as a pivotal moment. Baskin's design for the first issue is still the basis for the way MR looks today. John Hicks signed on for the long haul. Joseph Langland and Stanley Koehler became the first poetry editors.

We printed the memorandum that spawned MR in our 2003 Festschrift for Jules, since he was the author of that bureaucratic Genesis. Most of the document is focused on details of content, funding, design, organization, and so forth. But the nerve of it—the romance of it—is flitted over in a sentence, as too obvious to reiterate: "From our point of view as critics, scholars, teachers, the desirability of such a publication needs no comment."

Ah, Jules, the volumes you left unspoken there. . .

It is a strange desire. In the old offices in the cellar of Memorial Hall, the only windows were way up by the ceiling, oozing miserly light through patinas of amber nicotine. The air was close, with tobacco smoke blowing through monastic passageways between stacks of back issues, exchange copies, and file folders. Mel Heath perched her glasses on the tip of her nose like a disciplining headmistress. Under weak-tea lamplight in a corner, Bob Tucker performed another dissection of a manuscript, surrounded by the tools of his trade—reference books and ashtrays. Carol Fetler served visitors steaming platters of gossip, political outrage, back issues, and perhaps a martini. Once in a while an editorial eminence, a John Hicks or Sid Kaplan or Fred Robinson or even Jules himself, would rush in, issue executive orders, and race off to class. It looked like Bob Cratchit's office sunk into anarchy during an unaccountable absence on the part of Mr. Scrooge.

Today, we find ourselves in the cellar of South College, a nineteenth century dormitory, in a suite that was once a stable for the students' horses. There's less gin in the fridge, and no more of the honey-roasted peanut debauchery that scarred the reign of Managing Editor Christian Hawkey. The smokers go outside (this usually empties the premises).

The reason for the vices common in editorial work? Rejecting. The principal labor of the office is handling thousands and thousands of manu scripts a year. A young intern from the MFA program must feel like a cow invited to work in a slaughterhouse, abetting the abattoir by which they feel victimized the rest of the week. Some interns, like Mike "The Rejection Machine" Dockins, acquire a perverse taste for refusal, to the point where they are compelled to found their own magazines (in Mike's case Redactions) to indulge their foul desire. Yet there is a kharmic price for all this dashing of dreams that can, in its most salient manifestations, take the form of self punishment by smoke, alcohol, or honey-roasted peanuts. Like Existentialist heroes, editors take these burdens upon themselves.

In the founding memo, Jules wrote a kind of fiduciary poem:

Money from 1) school, 2) department, 3) private sources

1—no—not yet

2—almost nothing

3—who?

Verses that seem fresh even today, unfortunately. Desirability, but whose desire? The editors, that they should work a forty-hour week without pay? The readers, who have to be stopped one in three, as if by the Ancient Mariner? Contributors, who get paid about the same wages as in 1959? I do not know if anything human really has this desire. But who's completely human these days?

Some of the social causes this magazine has espoused have slowly triumphed. The founders of the Massachusetts Review actively solicited the work of black writers, artists, and scholars, then printed it right next to Robert Frost and Cleanth Brooks and William Carlos Williams and Leonard Baskin. In our time, Jim Crow died by agonizing degrees. African American studies grew into a doctoral-level academic discipline. Barack Obama was born during Volume 2.

MR has more founding fathers than mothers, because—and here you must pinch yourself to remember—there were few women on the faculty. Hiring a woman assistant professor remained a radical act till the mid-1970s. In 1972, we published Woman:An Issue, edited by Lee Edwards, Mary Heath, and Lisa Baskin. It featured work by a real feminist pantheon, including Lucille Clifton, Bella Abzug,Anais Nin, Angela Davis, Johnetta Cole,Maxine Kumin, Sonia Sanchez, and Anne Halley. It was an internal as well as an external statement. With Edwards, Heath, and Baskin, and with Doris Abramson, Esther Terry, Anne Halley, Leone Stein, Oriole Farb Feshbach, Ellen Dore Watson, Corinne Demas, and all the others, we've had a feminist pantheon all our own.

Refugees from Hitler and Stalin lived to see new diasporas rippling over the world, until nations no longer knew themselves in the mirror. The migrant experience, one of MR's earliest and most durable narratives, became a story with global resonance. A new academic project, Post Colonial Studies, sprang up everywhere to consider new transnational kinds of culture and identity. Edward Everett Hale's "Man Without a Country" is now a citizen of the world.

Where thought and the arts blossom, there are always women who love women and men who love men. And so it is inescapable that any literary quarterly would count them among its contributors, many years before the topic could be broached in civil conversation. The progression from Germaine Bree (orientation unnoted in the contributors' notes, of course) in our second issue in 1960, to John Emil Vincent's Especially Queer Issue in 2008, has been a widening roadway rather than a new route. The Canada issue of 1990, edited by Robert Schwartzwald, is a milestone on this path. After slow years had passed, we witnessed a florescence of civil rights that makes gay marriage old news here in Massachusetts—and coming soon to a state near you.

Whenever injustice is done to people because of who they are or what they think and say, the Massachusetts Review raises its small voice in protest. History, the long of it, is on the side of justice. Even though every day every thing seems to go wrong.

Who hasn't dreamed of starting a magazine? Far fewer have pondered the near-oxymoronic future of a magazine half a century old. How to make tradition hatch out innovation? What if the tradition is a tradition of innovation? How to balance the past and future so skillfully as to make a present of it?

For this issue we might have collected the best of the past, a kind of greatest hits compilation. But where is the future in that? We thought perhaps of assigning a piece from the past to present-day contributors, and asking them to react to it in some way or another—by a rebutting argument, or an updated story, or a new poem springboarded from the old. But finally we realized that we know better, that neither art not thought can be produced on cue, and solely in reaction to something.

Our various departments have done different things. The art editors, Pam Glaven, Christin Couture, and Oriole Farb Feshbach, are assembling a ret rospective exhibition of original art from over thirty Massachusetts Review covers to be hung in the University Galley in the Fine Arts Center at UMass. It will also display the covers of every issue, all five decades, as a sort of timeline. Historical ephemera, letters, broadsides, and off-prints will be showcased at the UMass W. E. B. Du Bois Library in conjunction with the University Gallery exhibition. Nearly two hundred covers make for a lot of exhibition space, worth a long, slow walk through that gallery-in-time.

Poetry editors Ellen Doré Watson and Deborah Gorlin decided to ask for new work from longtime contributors, some of whom we published early in their careers, and also to reprint a poem by e.e. cummings as a reminder of what's lurking back there. Then they selected (and asked a few friends of the magazine to select) first-time contributors whose work they wanted to share with our readership. Fiction and non-fiction, meanwhile, solicited work from past contributors, especially those for whom MR has had a significant role in their careers. And then some work from people new to us, famous and unknown. Tom Dumm arranged for our conversation with Cornel West, and edited the result. Our tireless fiction readers, Bob Dow, Bob Erwin, Corinne Demas, Patti Horvath, Elizabeth Porto, and many others, fish good stories out of the tidal sludge, a perpetual search and discovery.

It's important to salute the recent managing editors for their contributions to the modernization and maintenance of the thing. Christian Hawkey, who was near the end of his tenure when I arrived, went on to help found Jubilat and now teaches at Pratt Institute. Corwin Ericson was instrumental in bringing the operation into the twentieth century? a great leap forward in 2003. Katie Winger got one and a half of our feet into the twenty-first, and hosed out the financial sty we were living in. And kudos to our incumbent, Aaron Hellem, whose tenure has involved, it seems, one special event after another: special prizes, special issues, special attention, special favors, special rates, and ice storms.

We hope all our readers will come and celebrate with us at UMass on April 24 and 25, when we join forces with the Juniper Festival to present two days of readings, talks, panels, and exhibitions, all in the University Gallery. The annual Anne Halley Prize Reading will be held on Friday, April 24, as part of our weekend celebration. This years winner is Marilyn Hacker. Saturday afternoon at 3:00, Thomas Glave and Kelly Link will read, and at 8:00 that evening, a triple bill of Yusef Komunyakaa, le thi diem thuy, and Lucy Corin.

I imagine how quaint the previous announcements will sound when the editors of the hundredth anniversary quadruple special issue do their review of the century. Haw, they will say, they went to readings! With the writer actually there! I can't believe they printed poems on paper. What were they thinking? We're so thankful that the modern magazine can be directly intuited through our wetware interfaces. We're so glad that it takes just half a second to read a novel. What can those old days have been like?

David Lenson

for the editors.

Entries

fiction

The Americans

By Lê Thị Diễm Thúy

poetry

The Birth of the Poem

By Adélia Prado, Translated by Ellen Doré Watson

translation

The Birth of the Poem

Ellen Doré Watson

fiction

Eighteen Apocalypses

Lucy Corin

poem

Climbing Toward the Peaks

Robert Bly

nonfiction

Notes on the Mono-Culture

By Mark Edmundson

poetry

Pomegranate

Marilyn Hacker

nonfiction

You Can't Tell a Book by Its Cover?

By Grace Glueck

poetry

July 12, 2006

By Vénus Khoury-Ghata, Translated by Marilyn Hacker

translation

July 12, 2006

Marilyn Hacker

interview

A Conversation with Cornel West

By Thomas Dumm and David Lenson, With Cornel West

poetry

Foghorns

By Tony Hoagland

nonfiction

Music Is Force

By Arun Saldanha

poetry

Tutti Frutti

By Charles Wright

nonfiction

People's Politics: Amiri Baraka, Hip-hop, and the Dialectical Struggle for a Popular Revolutionary Poetics

By Casey Hayman

poetry

Rain

By Rita Dove

fiction

Ask ZZ if You Don't Believe Me

By Elizabeth Denton

poetry

I Like Aluminum Foil for It Has No Emotions

By Dara Wier

nonfiction

No Name Commune

By Marianne Boruch

poetry

Sayonara Marijuana Mon Amour

By Chase Twichell

poetry

On Being Asked What Result of Racism Would You Have Difficulty Giving Up?

By Aracelis Girmay

poetry

Stolen

By Shira Erlichman

poetry

My Love is Like Oh

By Christopher Kang

poetry

God

By Amy Leach

poetry

Helwa's Stories

By Deema Shehabi

fiction

The Ghost of Stephen Foster

By Aaron Hellem

poetry

The Years Between Wars

By Steve Orlen

nonfiction

Global Art, National Values, Monumental Compromises: "German" 9/11 Commemoration in America, "American" Holocaust Commemoration in Germany

By Peter Chametzky

poetry

Palm Reading

By Barbara Ras

fiction

The Door Man

By Lisa Vogel

poetry

Yakov

By Philip Levine

poetry

The Day We Buried You in the Park

By Martín Espada

fiction

Golden Birds

By Robert H. Abel

poetry

At the Pitch

By Maxine Kumin

nonfiction

Richard Dawkins: My Encounter with a Heartthrob

By William Giraldi

poetry

Where Are You Now?

By Naomi Shihab Nye

fiction

Pure Love

By Amy Bordiuk

poetry

The Wisdom of Solomon

By Brigit Pegeen Kelly

poetry

This Morning I Pray for My Enemies

By Joy Harjo

fiction

Apples and Angels

By Elizabeth Collins

poetry

Value

By Christopher Howell

fiction

Love Is the Crooked Thing

By Stephen O'Connor

poetry

Poem

By e.e. cummings

Table of Contents

Introduction

I . Ends and Beginnings

The Americans, a story by Lê Thị Diễm Thúy

The Birth of the Poem, a poem by Adélia Prado,

translated by Ellen DoréWatson

Eighteen Apocalypses, fiction by Lucy Corin

Climbing Toward the Peaks, a poem by Robert Bly

Notes on the Mono-Culture,

an essay by Mark Edmundson

Pomegranate, a poem by Marilyn Hacker

You Can't Tell a Book by Its Cover?,

an essay by Grace Glueck

July 12, 2006, a poem by Vénus Khoury-Ghata,

translated by Marilyn Hacker

II. Harmony

A Conversation with Cornel West,

by Cornel West, Thomas Dumm, and David Lenson

Foghorns, a poem by Tony Hoagland

Music Is Force, an essay by Arun Saldanha

Tutti Frutti, a poem by Charles Wright

People's Politics: Amiri Baraka, Hip-hop,

and the Dialectical Struggle for a Popular

Revolutionary Poetics, an essay by Casey Hayman

Rain, a poem by Rita Dove

III. Utopia in Ruins

Ask ZZ if You Don't Believe Me, a story by Elizabeth Denton

I Like Aluminum Foil for It Has No Emotions,

a poem by Dara Wier

No Name Commune, a memoir by Marianne Boruch

Sayonara Marijuana Mon Amour,

a poem by Chase Twichell

IV. Hand-Picked Poets

On Being Asked What Result of Racism Would You

Have Difficulty Giving Up?, a poem by Aracelis Girmay

Stolen, a poem by Shira Erlichman

My Love is Like Oh, a poem by Christopher Kang

God, a poem by Amy Leach

Helwa's Stories, a poem by Deema Shehabi

V . Ghost Memory

The Ghost of Stephen Foster,

a story by Aaron Hellem

The Years between Wars,

a poem by Steve Orlen

Global Art, National Values, Monumental Compromises:

"German" 9/11 Commemoration in America,

"American" Holocaust Commemoration in Germany,

an essay by Peter Chametzky

Palm Reading, a poem by Barbara Ras

The Door Man, a story by Lisa Vogel

Yakov, a poem by Philip Levine

The Day We Buried You in the Park,

a poem by Martín Espada

VI. I Carried the Things I Loved in a Red Sack

Golden Birds, a story by Robert H. Abel

At the Pitch, a poem by Maxine Kumin

Richard Dawkins: My Encounter with a Heartthrob,

an essay by William Giraldi

Where Are You Now?, a poem by Naomi Shihab Nye

Pure Love, a story by Amy Bordiuk

The Wisdom of Solomon, a poem by Brigit Pegeen Kelly

This Morning I Pray for My Enemies, a poem by Joy Harjo

Apples and Angels, a story by Elizabeth Collins

Value, a poem by Christopher Howell

Love Is the Crooked Thing, a story by Stephen O'Connor

Poem, a poem by e. e. cummings