Volume 35, Issues 3 & 4

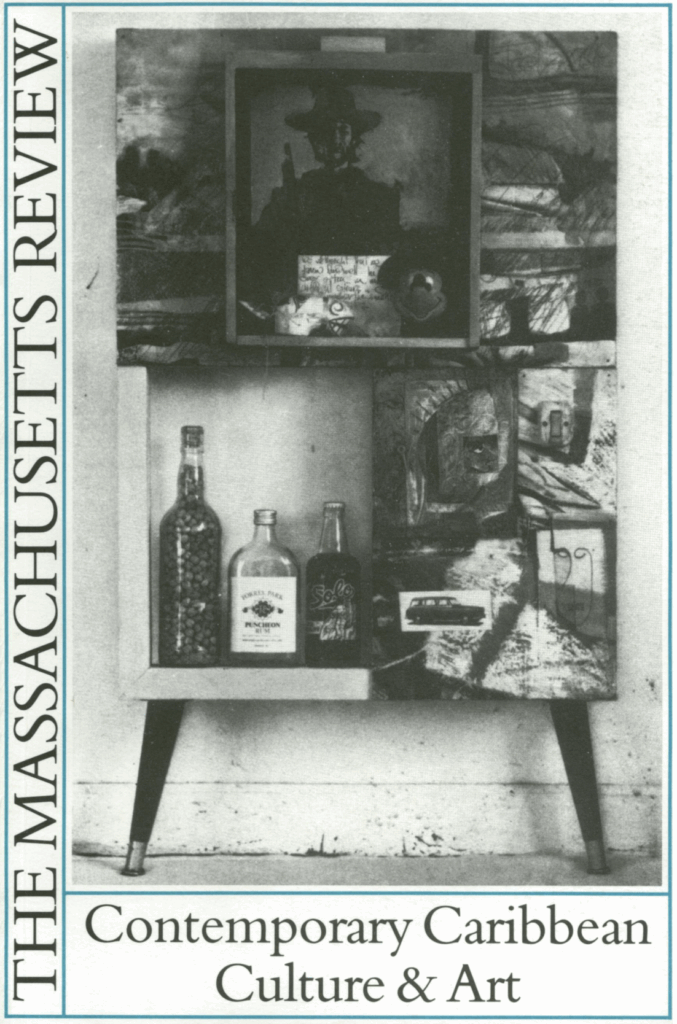

FRONT COVER: Christopher Cozier

Why Does He Always Whistle That Tune While Washing the Car

MIXED MEDIA

So, you want to find out what really is happening in the Caribbean art world, or on the carnival scene, or in the theater, or with dub poetry? Go to the room behind a certain panyard around six o’clock before practice begins, or the rum shop be hind the studio down by the docks on Friday afternoon after work.

As you approach what you hope is the right door to that room, snatches of the conversation reach you between the slam of dominoes and the blare of the sound system “—representation— quality of light—I told you I would pay you back in U.S.—cultural relevance—a who seh Sammy dead?—pram! pram!” The closer you get, the more you feel the urgency, the hilarity, the desperation and the underlying seriousness in the voices. You open the door and everything stops. Everyone turns to inspect the intruder. In a fraction of a second they have worked out who you are. Then everyone is talking again. And yet you have this feeling that it is still quiet.

As a Caribbean person living outside of the region, I’ve been on both sides of that door. It’s not always clear how people work out who’s on the inside and who’s not. Certain foreigners have honorary status. Certain locals elicit a stony silence. There is a way that West Indians fix themselves when they know they are being inspected for the umpteenth time—an intuitive response, nurtured perhaps by innumerable slave auctions, external examiners, televangelists and oversized satellite dishes—that makes us shift infinitesimally in our seats at moments like these in what looks like a gesture of welcome, even deference, but is really a refusal to let the Other see into your soul.

So when I say: “Please send me something on contemporary anglophone Caribbean Culture for a special issue of The Massachusetts Review I’m putting together,” everyone responds, “Sure, man!” But they mostly don’t, or what they send sounds nothing like the conversation did before the door opened. All the creative energy and heady cantankerousness are missing. Time to formalize such conversations for outside consumption is a luxury in societies where currency values are being decimated faster than the natural fauna of the region and the senselessness of crime and poverty, in the words of short story writer Olive Senior, makes God look “one-eyed.” But people are writing, and painting, and creating and contesting all kinds of cultural agendas throughout the Caribbean and its diaspora. We do it so that we can hold on to some sanity and spirituality or hustle a few dollars in a world where value has many meanings and none. We do it because we have big mouths and enjoy playing mas’. We do it because, if we don’t, our points of view may get lost in the cacophony of old talk in the room behind the panyard, beyond the studio, or inside the rum shop.

So in the end it comes down to networks. By cajoling, eavesdropping, talking fast and plundering other publications, I have pulled together here a completely unrepresentative collection of voices and images culled from cultural conversations taking place within anglophone Caribbean communities today. Some times the only way I could catch a conversation was to lift material wholesale out of its original context. I hijacked two essays from the Trinidad art magazine Galerie with the active connivance of its editor Geoff McLean. If you read them closely, you will notice that, behind Derek Walcott’s generous tribute to the painter, Jackie Hinkson, and Chris Cozier’s thoughtful descriptions of work by Cabral and Beckles, a serious bacchanal is still raging in the backroom about what constitutes “Art” and what direction “committed” Caribbean visual artists should be taking. Gordon Rohlehr’s essay on folk culture is the text of an address to the Folk Research Centre in St. Lucia. He works hard in the piece to incorporate a variety of constituencies that have a stake in folklore in the region—the churches, the governments, the cultural nationalists and “the folk” (whoever they are—probably the brother of the guy holding the video camera filming the event). I don’t know that he finds a convincing way to get all the new constituencies he identifies into the same frame (American televangelists? yaadis?). But it’s his struggle to ar ticulate a dynamic cultural reality which I want the reader to understand. You see another version of that struggle in the essay by Natasha Barnes when she tries to locate where Chinese Jamaicans fit into the black/white contest for representational legitimacy in Jamaican beauty pageants. Yet another version informs Carolyn Cooper’s controversial insistence on a space from which to read, without censorship, the cultural politics of rhetorical violence and anti-gay sentiment in Jamaican Dance Hall music.

Bruce King’s forays into the Rockefeller archives reconstruct the steps by which the creative energy nurtured in those back room sessions establishes itself in the international arena. Thanks to the first wave of Caribbean cultural historians, we know about the little magazines, local patrons and international institutions that facilitated or disrupted all kinds of connections between Caribbean artists up to the 1950s. We know a lot less about the mechanics of cultural production since Independence. Where does the funding come from? How do the networks function? That, too, is part of the conversation that stops when the door to the backroom opens.

Autobiographical memoirs are a much-favored form of cultural expression among such established Caribbean writers as V. S. Naipaul, Derek Walcott, Jamaica Kincaid and, most spectacularly in recent months, Kamau Brathwaite in Barbajun Poems (1994). Two new voices here continue this tradition. Thomas Glave’s essay on growing up gay and Jamaican in New York and becoming a writer opens up a dialogue with Cooper’s piece on heterophobia and cultural chauvinism. The trains that thundered over his father’s vegetable garden in the Bronx pro vide a vivid metaphor for the ways in which aesthetic boundaries constantly are displaced and re-established in the Caribbean diaspora. Ramabai Espinet’s “Indian Cuisine” pushes past yet another cultural door that swings open and shut within the Caribbean itself, marking the shifting boundary between “Indianness” and “Creoleness” in places like Trinidad and Guyana. Sometimes it’s hard to tell where that door is until it slams shut in your face.

Visual clichés about “indigenous” peoples may seem in escapable, but Abigail Hadeed’s “Guyana-Rupununi 1994” juxtaposes such images in ways that help us see them from a different angle. She is one of a new generation of Caribbean filmmakers, photographers, and video artists challenging the relationship between the viewer and the object viewed that we have come to expect in glossy magazine spreads about the region.

My only criterion for selecting the creative writing that makes up the rest of this issue was that it be by contributors whom readers are not likely to have encountered as “Caribbean writers” in other publications. Honor Ford-Smith’s work with Sistren is well-documented. Few readers will have seen her poems, how ever, especially the new prose poems like “My Mother’s Last Dance.” Writers such as Kelvin James and Everton Sylvester usually are associated with American themes. But their sensibilities have been shaped by the Caribbean islands where they grew up, and it is important to read their work in this context as well. Jane King and Kendel Hippolyte remind us that there are poets in St. Lucia besides its famous Nobel laureate. Very few people, even in the Caribbean, think of the Bahamas, the Virgin Islands or Bermuda as part of the Caribbean literary loop. Yet, from political poetry to quiet, domestic fiction, I received more interesting materials from these locations (thanks in part to the good offices of Sandra Paquet and the Caribbean Writers Work shop at the University of Miami) than from many other, more familiar, addresses. Nicolette Bethel, the Bahamian author of our lead story, is one such accomplished new writer. “Eating the Raccoon” will hold you spell-bound until its very last word. Cynthia James has been around for a bit longer, but her stories and poems make use of a form of Trinidadian speech that is less familiar to readers outside the region than the more frequently heard Jamaican Patwah. The energy and symmetry of her work remind me of an exquisitely crafted carnival costume that comes to life only when the wearer dances in it. Although Erna Brodber’s novels are well-known within Caribbean liter ary circles, they have had a very limited circulation in North America. The extract from her forthcoming Louisiana, included here, may be difficult to follow because of its allusive, elliptical style. But once its rhythms take over, a deeply spiritual sensibility asserts itself.

Even in a double issue, space eventually runs out. Apart from a few poems by John Agard, Grace Nichols and Fred D’Aguiar, there is almost no work in this collection by Caribbean authors based in Britain or by some of the better-known poets writing out of Jamaica, Barbados or Canada. With any luck you will have heard about some of these writers through other conversations. Even without their inclusion, however, this issue may overwhelm. As you stagger out of the backroom, having consumed, so to speak, the literary equivalent of a joint, three rums and coconut water, half a plate of jerk pork and a leftover Big Mac—you may feel a twinge of cultural indigestion. That’s okay. Tomorrow, when the hangover wears off, you can go back and linger over just one thing—this time something that you really, really like.

—Rhonda Cobham-Sander

Table of Contents

Introduction, Non-Fiction by Rhonda Cobham-Sander

Eating the Raccoon, Fiction by Nicolette Bethel

At Sea, Poetry by Fred D’Aguiar

Blackout, Poetry by Grace Nichols

Folk Research: Fossil or Living Bone?, by Gordon Rohlehr

Port-of-Spain by Night, Poetry by Cynthia James

Soothe Me, Music, Soothe Me; Let the Tourist Play, Fiction by Cynthia James

Domesticity; Jealousy, Poetry by Jane King

Jackie Hinkson, introduction, Non-Fiction by Derek Walcott

Searching for a Way Out, Non-Fiction by Christopher Cozier

Conflict of Interest, Art by Francisco Cabral

Mancrab, Art by Peter Minshall

Sculpture Caribbean Basin, Art by John Stollmeyer

Outhouse, Art by Francisco Cabral

Once a Man, Art by Guy Beckles

“Lyrical Gun”: Metaphor and Role Play in Jamaican Dancehall Culture, Non-Fiction by Carolyn Cooper

Baychester: A Memory, Non-Fiction by Thomas Glave

Three Sonnets for Mister Kent; Castries, Poetry by Kendel Hippolyte

Face of the Nation: Race, Nationalisims and Identities in Jamaican Beauty Pageants, Non-Fiction by Natasha Barnes

West Indian Drama and the Rockefller Foundation, 1957-70: Derek Walcott, The Little Carib and the University of the West Indies, Non-Fiction by Bruce King

Guyana-Rupununi, 1994, seven photographs by Abigail Hadeed, with commentary by the photographer

Where the Remote Bermudas Ride, Fiction by Angela Barry

Liberation Theology, Non-Fiction by Lasana M. Sekou

Born Again, Poetry by Ras Changa

Prospero Caliban Cricket, Poetry by John Agard

A Place of Learning, Fiction by Kelvin Christopher James

Taino Rebirth, Poetry by Marion Bethel

Indian Cuisine, Fiction by Ramabai Espinet

Way to Wendell Wedding, Poetry by Everton Sylvester

Louisiana, Fiction by Erna Brodber

My Mother’s Last Dance, Fiction by Honor Ford-Smith

Contributors

John Agard was born and lived in Guyana until 1977 when he moved to Britain. He worked at the Commonwealth Institute for several years, giving talks, readings and workshops, but is now a freelance writer and performer of poetry for both adults and children.

Natasha B. Barnes is a doctoral candidate in the Dept. of English Language and Literature at the Univ. of Michigan where she is writing a dissertation on the formation of national identity in Caribbean literature and culture.

Angela Barry is an English Lecturer at Bermuda College, Bermuda. She has published an essay on the representation of Black People on British Television, and fiction in the anthology Palmetto Wine.

Born in Nassau, Bahamas, where she still lives and works, Marion Bethel writes poetry, fiction, drama and essays. She was awarded a James Michener Fellowship in 1991 and the Casa Prize, in 1994, for her collection of poetry, Guanahani, My Love, which will be published in a bilingual edition in 1995.

Nicolette Bethel is completing her work on Yoruba retentions in Bahamian Culture in the Doctoral Program at Cambridge Univ. Of her several performed plays, one, Music of the Bahamas, represented the Bahamas at the Edinburgh Festival, 1991. She has published several short stories and a book, Junkanoo: Festival of the Bahamas, based on work her father had begun before his untimely death.

Erna Brodber has been a Lecturer/ Research Fellow at the Univ. of the West Indies, as well as visiting professor at a number of US colleges. She has published two books, Jane and Louisa Will Soon Come Home and Myal, as well as papers and monographs in history and sociology. She is now developing reading materials for programs in the study of the African diaspora.

Born on the island of Aruba, Ras Changa has published one collection, Illegal Truth, and is a co-founder of the St. Martin Poets Society.

Rhonda Cobham-Sander, Assoc. Professor of English & Black Studies at Amherst College, is the co-editor of Watchers and Seekers, an anthology of writing by Black Women in Britain, and of a forthcoming edition of the Sistren Theatre Collective’s play Bellywoman Bangarang. Her critical essays have appeared in Research in African Literatures, Callaloo, and WLWE.

Carolyn Cooper is a senior lecturer in the English Dept. at the Univ. of the West Indies in Jamaica, where she has initiated the establishment of the International Reggae Studies Center. She is the author of Noises in the Blood: Orality, Gender and the Vulgar Body of Jamaican Culture.

Christopher Cozier is a multi-media artist and critic who writes about the challenges of contemporary Caribbean art. His most recent work, “Blue Soap,” a video installation, was presented at the 5th Havana Bienal in Cuba in 1994. He lives in Trinidad with his wife, also a painter, and three children.

Fred D’Aguiar grew up in Guyana. He has published three books of poems and made a documentary film for the BBC. His first novel, The Longest Memory, will be published by Pantheon in January 1995. He currently teaches creative writing in Maine.

A writer of fiction and poetry, a critic and academic, Ramabai Espinet was born in Trinidad & Tobago and has lived in Canada for many years. Her published works include a collection of poetry, Nuclear Seasons, an anthology, Creation Fire, and two children’s books. Her poetry/performance piece, Indian Robber Talk, was recently produced in Toronto.

Honor Ford-Smith was founding director and writer for the Sistren Theatre Collective. Her poems have appeared in several anthologies of Caribbean work. Her book Lionheart Gal: Live stories of Jamaican Women appeared in 1986.

Thomas Glave is a Fellow of the National Endowment for the Arts/Travel Grants Fund for Artists and is currently a writer-in-residence at Altos de Chavon in the Dominican Republic. His work has appeared in Mule Teeth, Callaloo, Gay Community News and is forthcoming in Best Short Stories by Black Writers. He lives in New York City.

Though a commercial and advertising photographer by trade, Abigail Hadeed has a passion for photographing theatre and the performing arts. Her first solo exhibition was in 1992 and she is presently the photographer for Eddie Grant’s Ice Records and for the Trinidad Theatre Workshop.

Born in St. Lucia, Kendel Hippolyte has published several collections of poetry, most recently The Labyrinth, 1993. His work, including a play, has appeared in various anthologies.

Cynthia James, a teacher and writer, lives in Trinidad, and has published a collection of stories, Soothe Me, Music, Soothe Me, and one of poetry, Iere, My Love, both published in Trinidad in 1990. She has also received several play writing awards, and writes articles on the theater.

Kelvin Christopher James was born in Trinidad and now lives and writes in Harlem, NY. His stories and poems have been published in a number of magazines, and a collection of stories, Jumping Ship and Other Stories and Secrets, a novel, were published by Random House.

Bruce King has held professorships in Nigeria, France, New Zealand, and several other countries, and is now an independent scholar working on a biography of Derek Walcott. He has written or edited a number of books, most recently V. S. Naipaul, published in 1993 by St. Martin’s Press.

Jane King has published two collections of poetry, In To The Centre and Fellow Traveler, as well as publishing work in magazines and anthologies.

Grace Nichols worked as a reporter and freelance journalist in Guyana before moving to Britain in 1977, where she published a novel, several children’s books and collections of poetry. Her first collection, i is a long memoried woman, won the 1983 Commonwealth Poetry Prize.

Gordon Rohlehr is a professor of West Indian Literature, Univ. of the West Indies. He has published three books, most recently My Strangled City & Other Essays (Longman, 1992), and has co-edited anthologies, Voiceprint, an anthology of oral and related poetry from the Caribbean, and The Shape of That Hurt & Other Essays, both published by Longman.

Lasana M. Sekou is the Editor of the St. Martin Newsday newspaper. He is part of a publishing circle that has published nine of his titles, one with an introduction by Amiri Baraka, and gives poetry readings in St. Martins and England. A Jamaican living in New York City,

Everton Sylvester records and performs his poetry with the band, Brooklyn Funk Essentials. He received the 1993 James Michener Fellowship, and his books include Riverrun, Gathering of the Tribes and Aloud.

Derek Walcott has won numerous awards for his poetry and plays, including a MacArthur Fellowship in 1981 and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1992. Apart from his accomplishment as a poet and as director of the Trinidad Theatre Workshop, Walcott is a gifted painter who works mostly in watercolors. He divides his time between Trinidad, St. Lucia and Boston, where he teaches drama and poetry at Boston University.

An earlier version of Thomas Glave’s essay, “Baychester,” is scheduled to appear in Mule Teeth, Vol. 1, #1, a new journal by the Dark Room Writers’ Collective. The essays by Derek Walcott and Christopher Cozier are reprinted from Galerie: Magazine, Vol. I, no. 2, 1992.