Volume 22, Issue 4

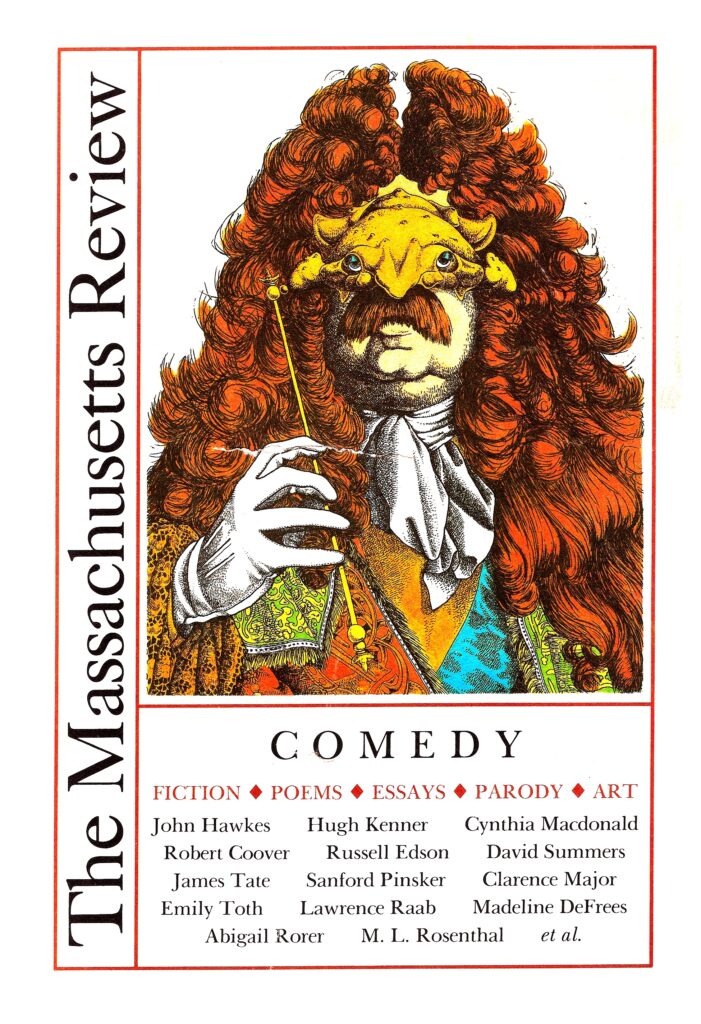

FRONT COVER: Abigail Rorer

CAPTAIN KANGAROO AS LOUIS XIV AT THE BAL MASQUE, 1980

HAND-COLORED ETCHING

FESTIVITY & INVENTION IN COMEDY

MANY PEOPLE WANT VERY MUCH TO READ COMEDY, AND NOT very many are writing it, at the moment. A colleague tells me that writers nowadays are not serious enough to write comedy; his opinion reveals an enlightened attitude towards comedy but is, as I hope this issue will demonstrate, unduly pessimistic. My hope is that this gathering of comic material will display some of the resources of comic writing and of writing about comedy—its many voices, its high spirits, its seriousness—so that in some small way readers, writers and editors alike will better recognize the important place comedy must occupy in our cultural life. After all it is Kierkegaard who said that “The comical is always the mark of maturity … The power to wield the weapon of the comic I regard as an indispensable legitimation for everyone who … is to have any authority in the world of spirit.” Yet it is telling that the comic aspect of Kierkegaard’s work has been ignored. We (Americans, Westerners) so often feel that maturity is a matter of gravity, that the comic is merely a minor relief from what should be the somber tenor of things, that if comic writing is inescapably important its comedy must be ignored or regarded as simply a passing effect, that comedy is fundamentally unserious and seriousness fundamentally uncomic.

As a counter to these shibboleths, here, in the following pages, is a variety of comedy come out of the woodwork, and enough good writing about comedy to help us place it in the proper perspective: as a way of shaping ideas that cannot be shaped in any other way, as a peculiar vision of the world, serious because it addresses important things in a peculiar way. For despite its variety—from X. J. Kennedy’s obscene quatrain to John Hawkes’ surreal deadpan—comic writing should be understood in its unique and essential qualities of festivity and gaiety.

In his lovely essay, “Paris Not Flooded,” Roland Barthes described how the flood of 1955 “partook of Festivity far more than of catastrophe.” This was because, as people boated about in their tasks of mending disaster, they experienced a ”rupture of the everyday”: objects seemed (or were) rootless, detached from normal utility, suddenly and euphorically strange. But because the objects were detached from the habitual, they became available for a more pleasurable manipulation, and so did not seem distorted or frightening or fantastic. Barthes describes the Parisians rediscovering the childhood joys of boating, of damming water with barricades, of enjoying a simplified landscape—all of this a festive activity because, although there had been a vast displacement of things, they still remained accessible for reconstruction and use. Life went on in a more surprising way. The dissolving of reasonable order did not describe a chaos. In the very process of being disorganized, what was familiar came closer to them, the important and mythic activities they enjoyed as children came closer to them.

Just so, the festivity of comic writing lies in the pleasurable manipulation of language in a rediscovery of the world. But one can so manipulate and so rediscover without comic pleasure. What is needed is the equivalent of the flood: a primal irruption that is not merely destructive. Barthes says that the flood “not only seized upon and displaced certain objects, it overwhelmed the very coenesthesia of landscape, the ancestral organization of horizons: habitual lines of the survey map, curtains of trees, rows of houses, roads, the riverbed itself, and that angular stability that so carefully prepares the forms of property, all this was blurred … no more paths, no more banks, no more direction.” This displacement of things and of our perception of them is festive only if we recognize that it is not ultimately threatening—if only we can, like children, remove ourselves from our reliance on order and reason and habit. Then we can begin, like children (those serious individuals!) to adapt ourselves, get out our boats and oars, and enjoy the action of creating and understanding our world again—not from scratch (for that is a heavy and heartbreaking task), but from what survives, what remains as unfirm but essential.

I stress, as Barthes does, the childlike quality of this festive activity, not to consign it to what is silly or sentimental (as adults often do, in the gravity of their attachment to habit), but to point out its gay seriousness. Children are busy at learning the names and functions of things, and as long as this activity is seen as a process of manipulation—the trials and errors of framing words and syntax, the discovery of several functions for simple objects, and so forth—the child can enjoy it. The manipulation is a discovering that knows no bounds of reason. It is when the process becomes strictly directed to the accomplishment of function learned from reason, that the pleasure ceases and the child becomes an adult who will have to work at, or be surprised into, recovering that profound festivity, the spirit of which is invention.

“Of all the strange things that Alice saw in her journey Through the Looking Glass,” what was “the one that she always remembered most clearly?” The gentle and foolish White Knight singing to her his melancholy nonsense song. The song is about invention. An inventor himself, the Knight sings a song of an inventor who listens to an old inventor—and all of them invent comically, that is, they invent, like children, what cannot work by the laws of reason and physics. The Knight ties anklets around his horse to guard against shark bites; the “I” of the song has a plan for boiling a bridge in wine to keep it from rusting; and the aged man he talks to looks for haddocks’ eyes in the heather so that he can work them into waistcoat buttons. Here we are at the heart of the matter: the wellsprings of invention are comic, expressing as they do the desire to explore and join and make, whatever the result. “‘Come, tell me how you live,’ I cried, / ‘And what it is you do!'” Well, we live and do by inventing, and the results are far from certain. If there is melancholy in this, there is gentleness and mildness and beauty in its pure absorption in making, and in the comic realization that what the mind puts together does not square with how the world operates. “The great art of riding,” cries the Knight as he continually falls off his horse, “is—to keep your balance properly.” He regards all his falls as “practice.” What he offers Alice, as she prepares to become a Queen (that is, an adult), is this comic illumination, and he offers it as a spirit of childhood for her as she makes her last step into a world where a more “dreadful nonsense” will occur—where, as the Red Queen says, “when once you’ve said a thing, that fixes it, and you must take the consequences.”

The White Knight’s nonsense does not dissolve all ordering; rather it transports us to that place—for which childhood is a potent example—where ordering begins, and is unfixed and free. In this sense, nonsense is the fundamental form of comic writing, dealing directly, as it does, with language invention. Much of the best comedy involves such invention, and the material in this issue illustrates this well.

In fact, we begin this issue with Robert Coover’s inventor, whose invention cuts corners that aren’t there, and instead of conforming to its intended functions, runs amok, turning the world topsy-turvy. This invention is love, not mind: the irrupting life of all we cannot control, the comic revenge of the body in its overleaping of limitation—what Adriane Despot, in her essay here, would call the clownish transformation of pattern and routine. She talks about how verbal comedy meddles with patterned language, so that sense seems to be an illusion. The spirit of invention is released, as in Russell Edson’s old woman, whose “bunions began to sing hymns in her shoes,” or in Lee Upton’s women scooping mayonnaise into their hair, or in James Tate’s minks sitting in “their old abbeys / and amphitheatres . . . / feeling lavish and cordial toward one another.” Suddenly we are confronted with a new world rising crazily from the syntax of the old, as in the magic act in Mary Koncel’s poem, during which everything seems overturned and bulging with mad life, but “still the show goes on,” including now the audience clapping for more. ” ‘Madness,’ ” says the lost narrator of Kenneth Rosen’s “Influenza Diary,” ” ‘is no masque of life! / But the quick of act become life’s all— / idiosyncratic, yes, worth less and real!’ “—a fine description of comic invention in all its creative disorder.

In the essay that accompanies his poems Rosen says that comic poems like his “attempt to overwhelm, to present experience in a manner as absorbing as a hallucinatory state.” This certainly would apply to the rich excerpt from John Hawkes’ new novel, which treats a bizarre subject with, in Rosen’s words, “sober, unsurprised and scrupulous attention.” Hawkes’ vision has the element of the grotesque that is at the heart of festivity: all life is related in a vast sensuality, generous with pleasure and pain alike, and no identity is firm. In Virginie’s story the grotesque has a liberating rather than a satiric effect in its testing of extremes. In the comedy of Ladislav Jerga’s story the world expands in Rabelaisian fashion to include a 500 x 800 foot photograph, a wedding in which several cousins marry the same Hungarian, who has the gift of being everywhere at once, and a newly-born babe who leaves a tip for his laboring mother. The life of an exile imagined as a magical, mythical world in which “what is and what is not ours” is confused, transforms pain into comedy in a celebration of flux. All these are landscapes like Barthes’ flooded Paris, involving “a whole euphoric myth of movement,” in which “disaster itself provide(s) evidence that the world is manageable.”

In Anne Bromley’s poem, “Slow Men Working in Trees,” the pun opens up a new and surreal world in which the unwonted is naturalized. In this essay on Joyce, Hugh Kenner reflects on the ways in which the puns in Finnegans Wake create their own astonishing language, so that reading and misreading become one comic activity, and we are nourished by the instability of written communication. The late Peter Farb, near the end of his survey essay on comic theory, makes a connection between understanding a joke and understanding speech: in both we process enormously complex material instantaneously. We “get” something, accord ing to laws of syntax, logic, reference. In the joke, however—and indeed, in all comic writing—the creativity of this process is made more evident, just as the mechanism of the process is exposed. What we “get” is something surprising, unwonted, and we get it anyway. Our habits become suddenly flexible, and invention is possible again. What a pleasure.

What makes Lawrence Raab’s a comic rather than a terrifying story is that its narrator accepts the game that everything that was usual, identifiable by name, can dissolve. “I just want to wait and see how things turn out,” he says. His unflappability is festive: he may well learn what his child already knows, that names are a game, and so the identities they fix are unsure: that the world is available—painfully but gaily—for invention: that things are. worthless and real! Barbara Reisner’s “The Coat Song” is a comic story because the detachment that allows Harriet to be funny about her relationship with her psychiatrist is the source of her being able to sing when things have come to nothing. The story is fundamentally about the singing that comes from nothing, not the painful diminishing itself, and it’s a comic song. Harriet will manage.

This issue begins, in Coover, with the invention of mind and ends, in Gilian Conoley’s poem, with someone vanishing “divinely barefoot”: death as it can only be described by the living. So it is that we can comically overcome anything final in a celebration of everything that moves, whether it stumbles, runs amok, or translates itself, in a constant inventing.

A final word should be added about Abigail Rorer’s beautiful etchings, those strange dances in the midst of desolation. They are—like so many of the references in the comedies here to animals and plants and potatoes and deflated balloons and “glorious energies”—comic testimonials to the life of the body, of the world’s body, ugly, triumphant and strong. They are realized images of a festival song whose variations we can hear throughout this issue.

Fred Miller Robinson

Table of Contents

Introduction: Festivity & Invention in Comedy, by Fred Miller Robinson

The Tinkerer, Fiction by Robert Coover

An Amorous Bestiary, Fiction by John Hawkes, drawing by Wang Hui-Ming

Rimini Diary & Plum Season: Comic Poems, Essay by Kenneth Rosen

Charity; Elephant Tears; A Dog’s Tail; The Restaurant Explosions; The Park Bench, Poetry by Russell Edson

Autochthonous; The Mink Cemetery, Poetry by James Tate

Slow Men Working in Trees; DaVinci Crashes in Joy Dawson’s Hog Farm, Poetry by Anne Bromley

After the Usual, Fiction by Lawrence Raab

Cubism as a Comic Style, Non-Fiction by David Summers

An Interview with the Oracle, Poetry by Jack Flavin

Some Principles of Clowning, Non-Fiction by Adriane L. Despot

Doing the Town in Cleveland, Ohio; Ho-Hum, Poetry by Mary A. Koncel

Etchings & Drawings 1977-1981, by Abigail Rorer; 10 Reproductions and an Afterword, by the Artist

Rolling Dogs; Emergency Cannibals, Poetry by Lee Upton

To the Point of Folly: Touchstone’s Function in “As You Like It”, Non-Fiction by David Frail

Postcard of Child Peeking Out from Under Its Mother’s Skirt; Supplanting the Beloved; Degrees of Pen/Man/Ship, Poetry by Cynthia MacDonald

The Jokes at the Wake, Non-Fiction by Hugh Kenner

Poem for a Refrigerator Door, Poetry by Alison Luterman

Late Late Fiction, Fiction by Ladislav Jerga

Instruments of American-Jewish Humor, Non-Fiction by Sanford Pinsker

Tattoo, Fiction by Clarence Major

Speaking Seriously About Humor, Non-Fiction by Peter Farb

LIGHT VERSE

Drawing by Hui Ming Wang

Some Differences, by Richard Wilbur

Coinland: Gold Bought Here; Acumen, by X.J. Kennedy

Shirley, Good Mrs. Murphy, by Sarah Provost

Hopkins: The Bedspring; Wordsworth: The Moose Flayer, by David Lenson

Female Wits, Non-Fiction by Emily Toth

Writer’s Diary, by Caroline Rosenstone

The Coat Song, Fiction by Barbara Reisner

Variations on the Edible Tuber, Poetry by Madeline DeFrees

Volatile Matter: Humor in Our Poetry, Non-Fiction by M. L. Rosenthal

Lust; Death, as Described by the Living, Poetry by Gillian Conoley

Contributors

ANNE BROMLEY‘s poems have appeared in Prairie Schooner, Mississippi Valley Review, and others. She teaches English at Virginia Polytechnic Institute.

A displaced Texan in the Northeast, GILLIAN CONOLEY used to be a reporter for a Dallas newspaper.

ROBERT COOVER‘s latest books are The Public Burning, A Political Fable, and Spanking the Maid.

Presently on a Guggenheim Fellowship, MADELINE DeFREES directs the MFA program at the University of Massachusetts. Her latest book of poems is forthcoming from Copper Canyon.

ADRIANE DESPOT is a free-lance editor in Washington, D.C.

RUSSELL EDSON lives in Stamford, Connecticut, is a printmaker and the author of seventeen books.

The late PETER FARB wrote Consuming Passions (1980), with George Armelagos.

JACK FLAVIN is a librarian in Spring field, Ma., and the author of a book of poems, Circle of Fire.

DAVID FRAIL is currently writing his Ph.D. thesis on William Carlos Williams.

JOHN HAWKES teaches at Brown University. His new novel, Virginie; her two lives, will be published this spring by Harper feRow.

LADISLAV JERGA has lived in Detroit ever since leaving Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Free-lance writer and editor, X. J. KENNEDY has just published an annotated anthology of invective, Tygers of Wrath.

HUGH KENNER is Mellon Professor of Humanities and chairman of the English Department at Johns Hopkins.

MARY KONCEL has published poems in The Titmouse Review and Virgin Mule.

DAVID LENSON teaches Comparative Literature at the University of Massachusetts, and is the best rhythm and blues sax player in New England.

ALISON LUTERMAN is currently working with Haitian refugees in Florida.

CYNTHIA MACDONALD, whose books include Amputations and Transplants, directs the Creative Writing Program at the University of Houston.

CLARENCE MAJOR presently teaches at the University of Nice.

Author of The Schlemiel as Metaphor, SANFORD PINSKER chairs the English Department at Franklin and Marshall College.

SARAH PROVOST runs The Nocturnal Canary Press of Pelham, Ma.

LAWRENCE RAAB, an NEA and Robert Frost Fellow, is the author of two books of poems.

BARBARA REISNER is a librarian in Allentown, PA.

FRED MILLER ROBINSON teaches at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and is the author of The Comedy of Language.

ABIGAIL RORER lives on a farm and tends pigs. She has done drawings for Houghton-Mifflin, David Godine and others.

Professor of English at the University of Southern Maine, KENNETH ROSEN directs the Stonecoast Writer’s Conference.

M. L. ROSENTHAL‘s most recent books are She: A Sequence of Poems and Sailing into the Unknown: Yeats, Pound and Eliot. His Poems: 1964-1980 will soon be published.

CAROLINE ROSENSTONE teaches in the expository writing program at Yale.

In the Art Department at the University of Virginia, DAVID SUMMER‘s most recent book is Michelangelo and the Language of Art.

JAMES TATE reports he is “currently on leave from [his] biography.” Nevertheless, he has published numerous books; the most recent is Riven Doggeries.

EMILY TOTH has just published Inside Peyton Place: The Life of Grace Metalious. She teaches at Penn State University.

LEE UPTON‘s poems have appeared in Salmagundi, Chicago Review, and elsewhere. She is presently living in Japan.

WANG HUI-MING, artist and teacher, is a frequent contributor to MR.

RICHARD WILBUR has been writer-in-residence at Smith College since 1977. His translation of Racine’s Andromache is forthcoming from Harcourt Brace.