Volume 28, Issue 3

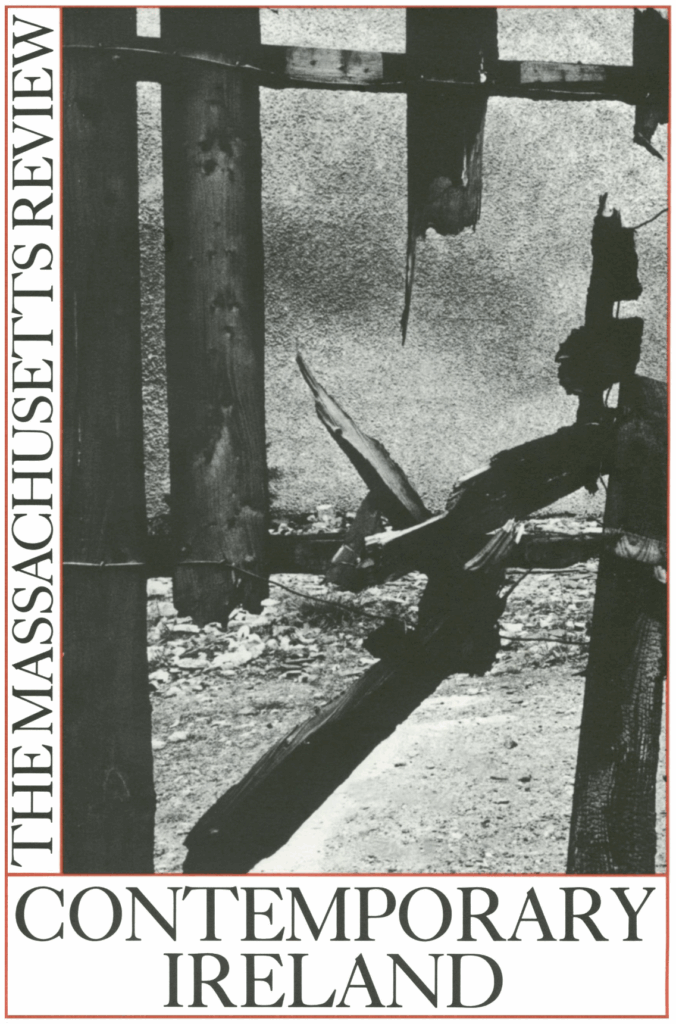

FRONT COVER: Gilles Peress

Same Day, Williams Street, Derry (Catholic)

In “Modern Ireland: An Address To American Audiences, 1932-1933,” W. B. Yeats wrote,

You may think that I over-rate some of the writers I have named, and [it] may be that I do so, for I am prejudiced in my favours, but I [am sure] of this: They are writing and living in the midst of the kind of historical crisis which produces literature because it produces passion.

Over half a century later, Ireland, as Auden might say, has her passions and her poetry still. Yet Ireland’s finest literature is shaped by more than passion. Yeats defined the challenge for Irish writers when, in “Meditations in Time of Civil War” (1928), he said that he wrote so that

My bodily heirs might find,

To exalt a lonely mind,

Befitting emblems of adversity.

More than forty years after Yeats published those words, when Irishmen were again engaged in what Padraig O’M alley has called “uncivil wars “in the streets and bogs of Ulster, Seamus Heaney wrote that Ireland’s writers faced new burdens and obligations: “From that moment, the problems of poetry moved from being simply a matter of achieving the satisfactory verbal icon to being a search for images and symbols adequate to our predicament. ” Here Heaney renews Yeats’s affirmation of artistic integrity during a time of political “troubles.” “Befitting” and “adequate” are terms which at once demand passionate intensity and artful control. Irish writers still seek such emblems, images and symbols, satisfactory verbal icons through which we can imagine a new Ireland.

Yeats’s essay was published in a special section of The Massachusetts Review (Winter, 1964), “An Irish Gathering: Letters, Memoirs, Poems, Articles of Twentieth-Century Ireland,” edited by Robin Skelton and David R. Clark. This important contribution to Irish studies emphasized the continuity of Irish writings by including works by and on writers of the Irish Renaissance–Yeats, Joyce, Synge and Shaw–along with contemporary voices: Richard Murphy, Thomas Kinsella, John Montague and others.

Events of the late 1960’s and subsequent responses by paramilitary organizations in Ulster, the governments of England and the Republic of Ireland, suggest a different, more discontinuous, state of Ireland. Thomas Kinsella finds a “gapped, discontinuous, polyglot tradition” in Irish life and letters. This “Irish Issue” of The Massachusetts Review emphasizes those Irish writers who came of age in a divided, static Ireland, a time when Unionist Stormont Parliament muffled dissent in Ulster and Eamon de Valera tried to create a Catholic, pastoral Ireland in the Republic. All seemed to change utterly for everyone on the island of Ireland after the renewal of “Troubles” in Belfast and Deny in 1968. (In 1972 England suspended Northern Ireland’s Parliament at Stormont; in 1975 de Valera, who had retired from active leadership and became his country’s President in 1959, died.) All of the writers here included, as well as many more who might have been included, were, in their lives and their arts, affected by political, social, economic and religious changes in Ireland. In particular, writers from Ulster–here represented by Seamus Heaney, Brian Friel, Michael Longley, Paul Muldoon and Derek Mahon–responded with original intensity to their transformed, divided homeland.

In a recent poem, “From the Republic of Conscience, “first published in a limited edition by Amnesty International, Seamus Heaney describes a poet’s journey to the Republic of Conscience, where “you what you had to. ” This is a humble land, where children are exposed to the sudden illuminations of lightning and leaders weep for their own presumptions of power. When the poet returns, his “two arms the one length, “he is unburdened by baggage; his only “allowance” is himself. The poet has become a “dual citizen, ” one who has been urged to represent Conscience and its citizens, one who will “speak on their behalf in my own tongue. “Each of these Irish writers represents the country of Conscience in his/her unique tongue. Taken together, these writers have fulfilled the prediction made by David R. Clark in his 1964 “Notes On An Irish Gathering”:

One leaves this Irish gathering, I think, with a sense of important work coming–the increased understanding of the great generation [of Yeats and Joyce] which new documents will supply, but, less calculably and more excitingly, the creation of new, individual, disciplined, and impassioned writing, by Irishmen of the second half of the Twentieth Century.

Shaun O’Connell

Editor

Table of Contents

Introduction, by Shaun O’Connell

The Emigrant Irish; Another Country; The Fire in Our Neighbourhood; Fond Memory; Fever; Suburban Woman; A Detail, Lace, Poetry by Eavan Boland

The Placeless Heaven: Another Look at Kavanagh, Non-Fiction by Seamus Heaney

The King of the Island; Conversations, Poetry by Michael Longley

The Soap-Pig, a poem by Paul Muldoon

Derek Mahon: The Lute and the Stars, Non-Fiction by Robert Taylor

A Decade of Seamus Heaney’s Poetry, Non-Fiction by John Hildebidle

Straying, Poetry by Brendan Kennelly

The Rag-Tree, Boherard; Carnaross 2; The Meadow; Dipping Day; Neighbors; An Open Fire; Caesarean; Madeline; My Care, Poetry by Peter Fallon

An Eye for an Eye: Northern Ireland, Summer 1986, Non-Fiction by Nan Richardson, photographs by Gilles Peress

Pilgrim’s Tale, Fiction by Maeve Kelly

The Persistent Pattern: Molly Keane’s Recent Big House Fiction, Non-Fiction by Vera Kreilkamp

The Summer of My Last Chance, Fiction by Jeannette Haien

The Silly and the Serious: An Assessment of Edna O’Brien, Non-Fiction by Peggy O’Brien

William Trevor’s “System of Correspondences,” by Kristin Morrison

Nono, Fiction by Julia O’Faolain

Friel and the Politics of Language Play, Non-Fiction by Richard Kearney

The Paradox of Ideological Formalism, Non-Fiction by David Krause

A Gathering From Elizabeth Corbet Yeats’ Dun Emer & Cuala Press

Contributors

Eavan Boland has written five volumes of poetry. Her selected poems are due from Carcanet in 1988.

This year Peter Fallon won the Meath Merit Award for Art and Culture, and is co-editing with Derek Mahon The Penguin Book of Contemporary Irish Poetry; he lives on a farm in north Meath.

Jeannette Haien‘s novel, The All of It, received the American Academy of Arts and Letters Kaufman Prize for First Fiction, 1987; she is a concert pianist.

Seamus Heaney‘s most recent book of poems is called The Haw Lantern. He is currently teaching at Harvard.

Poet, critic, and fiction writer John Hildebidle teaches at MIT and is at work on a study of 20th century Irish poetry. His latest book–of fiction–is Stubborness: A Field Guide.

Richard Kearney lectures in philosophy in University College, Dublin, and is co-editor of The Crane Bag, The Irish Review, and The Irish Literary Supplement. His latest book is Transitions: Narratives in Modern Irish Culture.

Author of Necessary Treasons, a novel, and Resolution, a collection of poetry, Maeve Kelly now lives in Co. Limerick and works as an administrator in the Refuge for abused women and children, which she helped establish.

Professor of Modern Literature at Trinity College, Dublin, Brendan Kennelly has written numerous books of poetry, two novels, and edited The Penguin Book of Irish Verse.

David Krause is Professor of English at Brown University and is presently editing the letters of Sean O’Casey.

Vera Kreilkamp teaches at Pine Manor College, Chestnut Hill, Mass., and is completing a book on the Big House novel in Anglo-Irish literature.

Born and raised in Belfast, Michael Longley is Combined Arts Director, Arts Council of Northern Ireland. His most recent book is Poems 1963-1983.

Kristin Morrison teaches English at Boston College and is part of the Irish Studies Program there. She is writing a book on William Trevor’s fiction.

Paul Muldoon was born in Northern Ireland and is currently teaching at Columbia and Princeton. His Selected Poems 1968-86 will soon appear from the Ecco Press.

Peggy O’Brien is presently Visiting Professor at Mount Holyoke College, on leave from Trinity College Dublin, where she teaches American literature.

Shaun O’Connell teaches at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, and has written numerous articles and journalism on Irish and American literature.

Irish fiction writer Julia O’Faolain‘s most recent U.S. publication is No Country for Young Men.

The photographer Gilles Peress has been photographing people and places in Northern Ireland since 1970; he is preparing a collection of those photographs with writer Nan Richardson supplying the text, to be published by Aperture in 1988 with the title An Eye for An Eye: Northern Ireland 1970-1987.

Robert Taylor is Professor of English at Wheaton College and Art Editor for the Boston Globe.