Volume 37, Issue 3

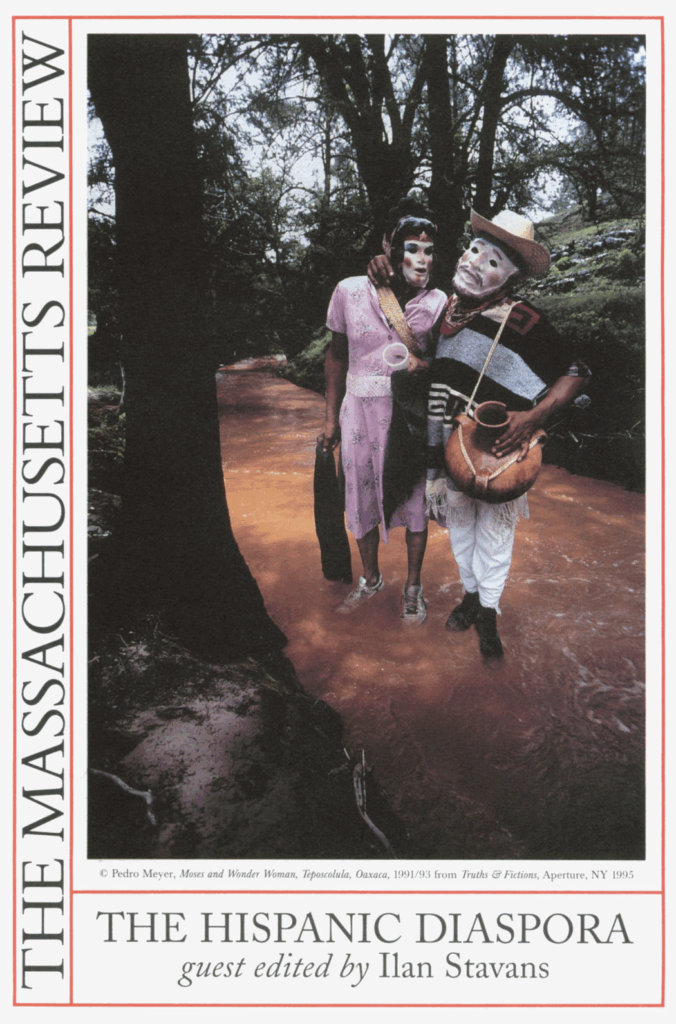

FRONT COVER: PEDRO MEYER

MOSES AND WONDER WOMAN,

Teposcolula, Oaxaca, 1991/93

From Truth & Fictions, Aperture, NY 1995

“If 20,000 el SALVADORANS or the same amount of Britons were to settle tomorrow in West Virginia,” asked Republican presidential hopeful Pat Buchanan not long ago, “guess who would assimilate faster and at far lesser cost to the people of West Virginia.” America, of course, loves stereotypes. Buchanan’s view is symptomatic of the way Hispanics are viewed north of the Rio Grande: uncontrollable numbers of them cross the border every day, looking to drain tax-payers by wasting their dollars in educational programs and health services they themselves won’t contribute a penny to; they are all lazy, primitive, hard-drinking, untrustworthy, and utterly foreign to the Anglo-Saxon sensibility; they refuse, in their unenlightenment, to learn the English language; and their history is a syllabus of barbarism that left both Spanish ancestors and Indian progeny physically and morally misshapen.

Often the general consensus is that the Hispanic world is a unified whole—or better, a unified hole—where a single monolithic race, the mestizo, what José Vasconcelos called la raza cósmica, flourishes by multiplying at great speed. This collective portrait, of course, is not only simplistic and ridiculous; it also manifests a total ignorance of Latin America, a land of immigrants since the immemorial, a melting pot where languages and idiosyncrasies mix but without a self-aggrandizing promotional machine capable of selling its byproduct to the rest of the globe. The literary pieces gathered in this special issue testify to the diversity and heterogeneity of the Hispanic people, polyphonic and multicultural, some 750 million scattered from Rome and the Patagonia to East Los Angeles, Israel and northern Africa.

I have limited the contents to stories, memoirs, conversations, and personal essays (no academic jargon, thank you!), and tried, as much as possible, to resist overexposed signatures. A third of the pieces are translated from the Spanish, and the rest were written in English but thought out in other tongues, including Arabic, Yiddish, Latin, Spanglish. Five of the contributors are under the age of 30, and five others are consummate masters. In one way or another, they are all itinerant travelers. Ana María Shua, a best-selling Argentine writer of Jewish descent born in 1951, has novelized the Jewish immigration to the southern cone in The Book of Memories, which still awaits publication in the United States. Her story “A Good Mother” is about motherhood as a diasporic existence. Rodrigo Rey Rosa, whose work has been translated into English by Paul Bowles, was born in Guatemala in 1958 and has lived a considerable portion of his life in Morocco. His story “The Worst of It,” set in a violent city where an Oriental learns an obscure Mayan language and human dialogue is eternally fractured, is about unwanted arrivals and forced departures. José Antonio Burciaga, a seasoned Chicano muralist, activist, and essayist, is responsible for Drink Cultura and Spilling the Beans. Raised in the West Texas border town of El Paso, he is a founding member of the comedy group Culture Clash. His story in this issue is part of an unpublished fiction manuscript. Cal vert Casey, known in the Havana of the sixties as La Calvita, was a white gay born in Baltimore in 1923 and raised in Cuba. He switched from English to Spanish—a unique transformation, since most literary tongue-snatchers, from Joseph Conrad to Joseph Brodsky, travel in the opposite direction, from a less to a more commercial language. Casey began his publishing career in the New Mexico Quarterly and then, in an astonishing revamping of his own self, produced a handful of admirable stories about alienation and internal exile, all forthcoming in a volume of his collected fiction by Duke University Press. His tragic descent to hell and his ultimate death in Rome, in 1969, chronicled by his friend Guillermo Cabrera Infante in Mea Cuba, were the result of his ”unwelcomed” sexuality under the regime of Fidel Castro.

Vivian Leal, Verónica González, and James López are also language dwellers: they are Latinos, north-of-the border Hispanics, whose linguistic negotiation, their navigating between English and Spanish, can be felt in various degrees, at times only as an unconscious rumor, in their pieces. But language is not the sole leitmotif of the following pages; so are race and politics. Irene Vilar, the granddaughter of a famous Puerto Rican independentista, chronicles in her memoir, which serves as a prologue to her forthcoming book A Message from God in an Atomic Age, her personal experiences in a psychiatric hospital and a family legacy where freedom and blood intertwine, where rape, metaphorical and literal rape, is considered the spark of history, and where women are always weaving their own death shroud.

Piri Thomas, well known for his classic 1967 autobiography Down These Mean Streets, explores issues of blackness (la negritud) and redemption in a Caribbean island and in the mainland. His stature as a role model to young Hispanic writers in the United States makes this rare conversation an invaluable tool to understand his identity as a dark-skinned Nuyorican. Also rare is Edward Rivera’s essay. His career mirrors that of Henry Roth. After his promising 1982 debut, Family Installments, published with the help of editor Ted Solotaroff, had gone through many reprints and had become standard reading in high schools and colleges, Rivera has fallen into a deep silence. He repeatedly claims to be at work on a sequel, but no portion has appeared in print. “Stable Manners” humorously recounts his odyssey through the publication maze: he is punished, time and again, for not being a homeless alcoholic, a careless father whose illegitimate children depend on welfare—in short, he is penalized for not being a stereotype. The lessons to be learned from this essay are many, particularly if one reads it in light of the current tendency of New York publishing houses to bring out Latino books at whatever cost, regardless of quality.

Always puzzling, always enchanting, is Augusto Monterroso, an erudite Guatemalan living in Mexico whose stature as a modern master of the short story and literary essay is internationally recognized (he is often compared to Borges), but whose exposure to American readers remains, sadly, almost non-existent. (His Complete Works and Other Stories, published in English translation by the University of Texas Press, is a book I would gladly take with me if I were to survive a plane crash in a deserted island.) In the following conversation Monterroso recalls reading the Greek and Roman classics in his Guatemalan adolescence—he is, by the way, the only Latin American writer ever to have a book of his translated into Latin—and discusses, among other themes, his world-famous one-line story “The Dinosaur,” as well as his one-line essay “Fecundity.”

The rest of the material offers various experiences of dislocation. Jack López Estavillo, in “Pathos, Bathos, and Mexiphobia,” reflects on the video-taped police beating of illegal Mexicans in the border—and is stupefied. José Matosantos ponders the hybrid nature of Salsa as a mirror of Caribbean identity. And Enrique Anderson-Imbert, a distinguished Argentine critic and scholar at Harvard, displays his fantastic storytelling talents to create a story of lo fantástico, much like those Borges and Julio Cortázar got us used to. Superficially, all the pieces in this issue might seem disconnected. They are not. What unites them is their ambivalence, their feeling of belonging to a fractured, heterogeneous culture, which Cortázar once masterfully described as el sentimiento de no estar del todo. The word “diaspora” brings to mind images of dispersion, but among Hispanics dispersion is not only geographical but spiritual, the result of a precipitous drive toward modernity. After all, as Octavio Paz once argued, Hispanic culture is modern in spite of itself; its people hold folklore and tradition sacred, but have trouble protecting them on the road to progress. A poor Zapoteca Indian begging in broken Spanish in the streets of Mexico City, a hysterical Buenos Aires mother struggling to retain control of her identity, a Guatemalan Latinist, a black Puerto Rican at home neither in an African milieu nor fully accepted among white Caribbeans, an American-born Cuban dreaming of a room of his own in Cervantes’ tongue—all of them are alien wanderers, salamanders in eternal metamorphosis, diasporic organisms each with a very different understanding of what Hispanic culture is all about.

Perhaps the safest way to approach the Hispanic orbit, as pictorial artist Pedro Meyer does in his extraordinarily stimulating digital collages, is as a territory of appropriations and masks, a complex site, made of endless diasporas, both internal and external, an aleph where all things happen at once and where originality is non-existent—or better, where the only way to be original is to be unoriginal. Its people communicate by means of European tongues: Spanish, Portuguese, French, English, Polish, Russian, and so on. They write novels and plays and poems, just as they were taught to by one foreigner after another. But they have revamped these artistic forms, injecting them with a hallucinating joi de vivre. Its people are white and black and brown and yellow and looking to understand why and where everybody can fit in. It is not a unified hole but a universe made of oldcomers and newcomers, both sedentary and explosive, who make love and masturbate, eat Kellogg’s Corn Flakes and arepas, read Gabriel García Márquez at a downtown Taco Bell and watch the latest chapter of a popular telenovela while planning the next revolution. No, the Hispanic world wasn’t created by a merciless deity, un dios de poca madre, looking to inflict suffering on the United States. It is autonomous, baroque, labyrinthine, self-referential, and has a life of its own, with ups and downs and in betweens, a point of arrival and departure, a myriad of possibilities—a fiesta of diasporas where everybody can be lost and found. If 20,000 El Salvadorans were to settle tomorrow in West Virginia, guess how enriched the people of West Virginia would be. It would take some education, though.

In this last line: a word of gratitude to José Matosantos, without whose help this issue would not have come together, and my wholehearted thanks to Pedro Meyer for permission to use an image from his masterful book Truths & Fictions. His subverting art is unparalleled in exploring the ever-shifting paths of the Hispanic diaspora.

—Ilan Stavans

Table of Contents

Introduction to the Hispanic Diaspora, Non-Fiction by Ilan Stavans

A Message from God in the Atomic Age: A Memoir, Non-Fiction by Irene Vilar, Translated by Gregory Rabassa

Pigeons, Fiction by Vivian Leal

Race and Mercy: A Conversation With Piri Thomas, Non-Fiction by Ilan Stavans

Pathos, Bathos, and Mexiphobia, Non-Fiction by Jack López Estavillo

The Worst of It, Fiction by Rodrigo Rey Rosa, Translated by Gilbert Alter-Gilbert

Stable Manners; Or, How The Publication of Family Installments was Stalled for Three Years and $3,000.00, Non-Fiction by Edward Rivera

Emilio’s Revenge–1960, Fiction by José Antonio Burciaga

The Skeleton, Fiction by Enrique Anderson-Imbert, Translated by Gilbert Alter-Gilbert

On Brevity: A Conversation with Augusto Monterroso, by Ilan Stavans

Cousin Myth; or, Beside the Tracks, Fiction by James Lopez

Between the Trumpet and the Bongó: A Puerto Rican Hybrid, Non-Fiction by José Matosantos

A Little Affair, Fiction by Calvert Casey, Translated by John H.R. Polt

A Good Mother, Fiction by Ana María Shua, Translated by Dick Gerdes

Come Like a Dog to Mama, Fiction by Verónica González

Contributors

Gilbert Alter-Gilbert is a Critic and translator living in California. He edited the anthologies Life and Limb and Pipe Dreams (both Hijinx Press).

Enrique Anderson-Imbert was born in Argentina in 1910. His literary career began in journalism, but in 1947 he was exiled to the United States under Perón and he entered academia. Best known as a literary critic, he has also produced various novels and short stories. His many books include Spanish-American Literature: A History (Wayne State University) and the story collections Woven on the Loom of Time (University of Texas Press) and The Other Side of the Mirror (Southern Illinois State University).

José Antonio Burciaga was raised in the West Texas border town of El Paso. He is a seasoned Chicano cultural activist, muralist, humorist and founding member of the comedy group Culture Clash. Burciaga lives in Monterrey. Among his works are Undocumented Love, awarded the Before Columbus American Book Award for poetry, Spilling the Beans and Drink Cultura: Chicanismo (both Joshua Odell Editions).

Calvert Casey was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1923, of Cuban parents. He was educated in Cuba but lived abroad from 1946-57, sometimes publishing in English. His first story appeared in the New Mexico Quarterly and won him a prize from the publisher Doubleday. After the outset of the Cuban Revolution, he worked as a magazine editor of the prestigious Casa de las Americas until forced to exile. He died in Italy in 1969. Casey published a collection of stories, El Regreso (Ediciones R), forthcoming in English by Duke University Press.

Jack López Eestavillo has an MFA from the University of California at Irvine. His work is featured in Iguana Dreams (HarperCollins), Current from the Dancing River (Hartcourt Brace), and Muy Macho (Anchor). He teaches at California State University at Northridge.

Dick Gerdes is a critic and translator. His translations include A World for Julius, by Alfred Bryce Echenique (University of Texas Press) and The Forth World, by Diamela Eltit (University of Nebraska Press). He teaches at The University of New Mexico.

Verónica González was born in Mexico City, raised in Los Angeles and now lives, writes and teaches in New York. She is currently at work on her first novel.

Vivian Leal is a Cuban-American writer who grew up in San Juan, Puerto Rico. She holds an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Her work is included in the upcoming anthology New World: Young Latino Writers (Delta). She currently writes and lives in Michigan.

James López holds a Master’s degree in Contemporary Latin American Narrative from the Universidad de Chile. Cousin Myth: or, Beside the Tracks forms part of his novel Emoria at the Tracks, a portion of which will be included in the upcoming anthology New World: Young Latino Writers (Delta). López is currently living in Miami, where he is completing a collection of stories written in Spanish.

José Matosantos is a graduate of Amherst College. A native of Puerto Rico, in Spring 1996 he was an Amherst College Copeland Fellow.

Augusto Monterroso, a native of Guatemala, has lived in Mexico since 1956. His books in English include The Black Sheep and Other Fables (Doubleday) and Complete Works and Other Stories (University of Texas Press).

John H.R. Polt is Professor Emeritus of Spanish at the University of California, Berkeley. His research has concentrated on modern Spanish literature, especially that of the 18th century. His translations include works by Juan Bautista Alvarado, Camilo José Cela, and Victoria de Stefano. His translation of the complete short stories of Calvert Casey is forthcoming by Duke University Press. The present translation of “A Little Affair” is from the 1962 edition of Casey’s El regreso.

Gregory Rabassa is an internationally renowned translator. His credits include the translations of One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Marquez, Hopscotch by Julio Cortazar, and Paradiso by José Lezama Lima. He teaches at Queens College.

Edward Rivera was born in Puerto Rico in 1944 and came to New York City at the age of seven. He graduated from the City College of New York and received an M.A. from Columbia University. His major work is Family Installments (Penguin), a semi-fictional memoir about a Puerto Rican family in New York’s El Barrio. Rivera teaches at The City College of New York.

Rodrigo Rey Rosa was born in Guatemala in 1958 where he completed his studies. He then lived in New York and Morocco. Paul Bowles has translated two collections of his work into English: The Beggar’s Knife and Dust on her Tongue (both City Lights). He has also been translated into German and French. Rosa divides his time between Morocco, Guatemala, and the United States.

Ana María Shua was born in Argentina in 1951. She has published children’s books, novels, and story collections, including Viajando se Conoce Gente and El Libro de los Recuerdos (both Planeta). She has received a Guggenheim Fellowship and currently teaches at the Universidad Nacional de Buenos Aires.

Ilan Stavans is a Mexican novelist and critic. His works in English include The Hispanic Condition (Harper Perennial), The One- Handed Pianist and Other Stories and Art and Anger: Essays on Politics and the Imagination (both University of New Mexico Press). He is currently editing The Oxford Book of Latin American Essays. Nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award, he teaches at Amherst College.

Piri Thomas lives in Berkeley, California. His classic autobiography Down These Mean Streets (Penguin) was published in 1967. His other books include Savior, Savior, Hold My Hand and Seven Long Times (both Arte Publico Press).

Irene Vilar was born in Puerto Rico and graduated from Syracuse University. She has co-authored a children’s book, Diario de Viaje (Scholastic), and is currently working on a novel. She divides her time between Syracuse and Man-o’ War Cay, Abaco, in the Bahamas. Her piece in this issue is the prologue to her book A Message from God in the Atomic Age, to be published by Pantheon later this year.

cover artist: Pedro Meyer has won numerous awards for his photography, including a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, with which he supported his many photographic expeditions represented in his book Truths & Fictions. Meyer’s innovative use of the medium was also featured prominently in Metamorphoses: Photography in the Electronic Age (Aperture 136, 1994). A traveling exhibition of Truths & Fictions will be on view at major museums in Europe, Mexico and the United States through 1997.