Volume 47, Issue 2

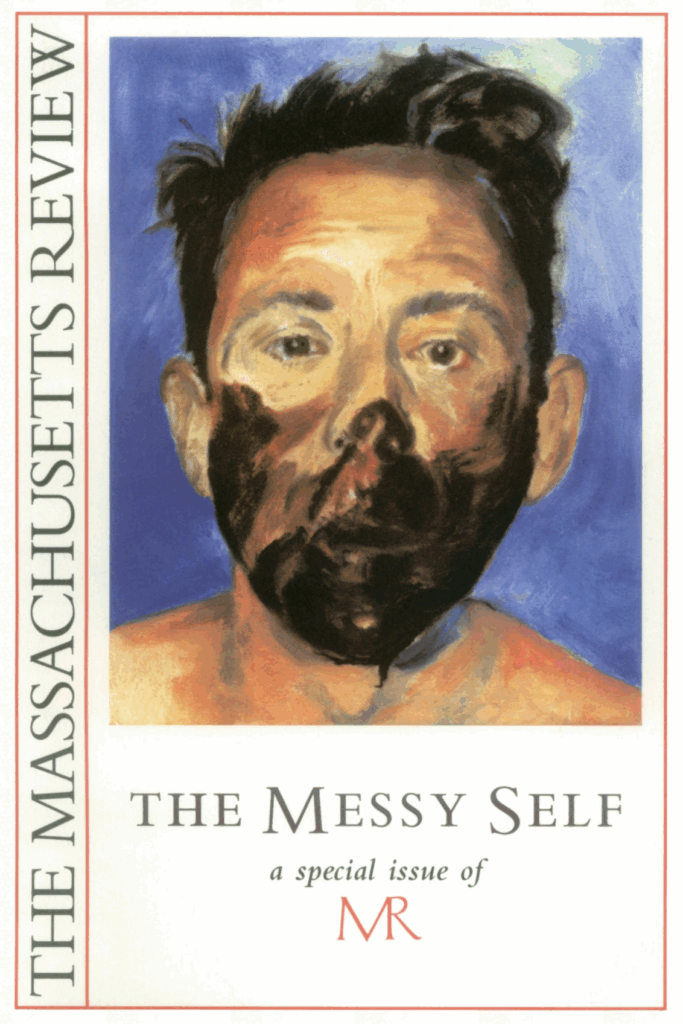

FRONT COVER: Lee Gordon

The Chocolate Eater, 2006

OIL AND PENCIL ON CANVAS

11 X 14 INCHES

I am large; I contain multitudes.

Walt Whitman

One must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star.

Friedrich Nietzsche

THERE IS NOTHING SIMPLE about being a self. Even the drive for simplicity is complicated; the yearning for tidiness, messy. Being a self is messy and we are messy selves. We are ambivalent when we yearn to be resolute and restless when striving for calm. Our feelings clash, our wills waver, our desires are incompatible. Our minds take leaps that defy logic; our dreams visit us as decodable illogic. We are only partly rational. Our growth is rarely linear. We can think in wishes and deny reality. Even as we doubt and deceive ourselves, we are creative, evaluative, and self-interpreting. And, always, we live with the possibility of falling apart.

The instability in our constitution is not a modern phenomenon. It is part of human nature; it has been true of us for as long as we have existed.The ancients recognized interior conflict, but it was the moderns who squarely acknowledged the disorder, the irrationality and the disharmony at humanity’s heart. Freud, like Plato, conceived of the self as constituted of parts, ideally reconcilable yet always (and in reality) prone to clashing. But where Plato saw irrationality issuing from clashes among the self’s elements, Freud saw irrationality inhering in the elements themselves, thereby locating the roots of our chaos and disorder far deeper than in the incidental clashing of ordered parts. Freud’s view of the irrational self was echoed in other modern movements, like cubist painting, atonal music, expressionistic literature, and existentialist theory, each reacting against classical and Enlightenment themes and together eroding confidence in thoroughgoing rationality, order, and contented civilization. The self—and indeed the universe in its entirety—lay largely outside the categories of human understanding.

We manifest a variety of reactions to this modern diagnosis of unreason: reactions of struggle, of acceptance, of denial, and alter nations between. Denial is a favored strategy when our messiness gets too uncomfortable. We tidy our work-desks and our houses and find ourselves buoyed by the promise that we ourselves might thereby be tidied. We saturate ourselves with antidotes to ambiguity and uncertainty, and grope for methods to reduce tension and ambivalence. We read magazines like Real Simple. We respond to the chaos that lurks beneath the thin veneer of civilization by rubbing another coat of polish on the veneer.

Our discomfort obscures the fact that breaks in reason enable creativity; that doubts lead to richer analysis and evaluation; that discordances bring texture to relationships that would otherwise be flat. The image of a tidy self is reassuring, yet falsely so. To tidy up our messes, or to deny them, can lead to an impoverished life: a narrowing of our aspirations, a stunting of our creativity, a less robust recovery from our traumas, paler friendships, and muted loves.

A messy self may be disconcertingly easy to relate to, identify with, and describe. But it is by no means easy to define. Indeed, a tidy definition will miss the point. My own field of contemporary analytic philosophy works predominantly with an ideal of the self as resolute, unified, and rational—an ideal I question, as surely as I fail to achieve it. This ideal is, of course, championed by the larger culture, with added emphasis on simplicity and its dangerous relative, oversimplification, exercised in much of public, especially political, discourse. I have felt propelled—by a sense of alienation from this ideal and the reductionism it encourages—to seek out new ideals and conceptions of self that can accommodate the ambivalence, incoherence, and irrationality that mark our human experience. As a starting point, I have invited thinkers from a variety of disciplines to write of lives, and of selves, that are—in a word—messy.

At the risk of appearing orderly, the writings in this MR issue broadly span five categories: love, self-understanding, self-deception, identification, and well-being.

Love takes many objects and forms; it pulls us in many directions. In the words of Jonathan Lear, “it establishes an ever present undertow.” Some have thought that love is a longing for beauty or for goodness. Others have speculated that love aims to restore a lost unity with another. In Aristophanes’ myth, as depicted in Plato’s Symposium, love is a pressure to be reunited with our long-lost halves. In Freudian theory, it is a drive to restore our own pasts, a longing to return to an un-individuated, merged state.1 In some traditions of thought, love ascends toward greater fulfillment, understanding, and flourishing; in others, love descends, with humility, into longing, incompleteness, and passivity.2

Certainly, loving is a messy venture in which boundaries blur, dependencies transfer, self-conceptions are lost and traded and reclaimed. Diane Ackerman aptly titles her poem “A Strange Disorder,” and in it she deftly hunts out what is haunting both about caution and about passion. Gayle Pemberton celebrates love’s power to affirm and heal, even if through tics, in “My Tourette’s.” In “Conservation,” Debra Spark evokes sheer long ing in a characters unmet desires for connection and comfort. Beth Ann Fennelly’s poem, “Mommy at the Zoo,” grapples with the dissolution of memory (and self?) in the throes of mothering. Jane Crosthwaite’s “Prologue for Psyche” orients us to the layers of identity-contortion and moral challenge we confront in Wendy Wasserstein’s never-before-published play. In Psyche in Love, Wasserstein dramatizes love’s messiness in a tale of betrayal and regained trust, through a sloughing off of sister-selves and a slathering on of beauty creams. John O’Donohue’s “Since You Came” captures what utter transformation can come in the encountering of another.

“This ramshackle, this unwieldy, this jerry-built assemblage/ this unfelt always felt disarray; is this the sum of me?” In C. K. Williams’ poem, “The Clause,” we witness a mind reaching to unfold the layers of its own unknowability, and we share in its unease to forge on as it cannot help but do, with longing and with judgment. In “The Last Place on Earth,” Patricia Foster exposes an illness-shattered core, as she struggles against a break down that neither she nor her doctors understand. In Mary Kinzies poem, “Facing North,” the self is out of place, a traveler pilgrim for whom attempts at self-understanding and repair result in new brokenness. Each of these writings represents a quest for deeper self-understanding, for clues to identity, even legitimacy, and for pathways to wellness. Rebecca Goldstein works from the process of writing itself, to show how we become receptive to large truths that transcend our personal experience when we enter into the lives of the fictional selves we write about and read. Knowledge seeps in as the bounds and constraints of person hood and time are loosened in our engagement with the selves of fiction. In “The Real Story,” Liv Pertzoff artfully questions whether a bounded self, or story, makes any sense at all.

Of course, our desires to know ourselves and our world are most times tempered by our suspicions and fears of what we might discover. The strategies by which we perpetuate our own ignorance and befuddlement are numerous, and whether or not we intentionally deceive ourselves or engage in less paradoxical strategies there is no doubt that we do much to avoid facts about ourselves that would be difficult to confront. Perhaps human flourishing requires judicious doses of self-deception. Certainly, we can tolerate even injudicious doses without apparent loss of integration. In “The Superficial Unity of Mind,” Sarah Buss con tends that an integrated sense of self requires only the most superficial unity. Our powers of self-interpretation enable us to accommodate a vastly heterogeneous set of impulses and to toler ate, even if by glossing over, very deep internal conflict. According to Steven Pinker, what is intolerable to a sense of self is not its disunity but the idea (and evidence) that one is not as beneficent and effective as one would like people to think. In “Kidding Ourselves,” Pinker shows the ingenuity of minds threatened by the appearance (and reality) of a lack of “beneffectance.”

Conflict amongst our desires, hopes, dreams, and beliefs may challenge our sense of authenticity, even if it does not challenge our sense of unity. What is it to be authentic? And how do we emerge as individuals, related to others through sameness and through difference, in the larger community? In Ilan Stavans’ “The Disappearance,” the authenticity of a self is so compromised—the boundaries of reality and fantasy so blurred—as to prompt an interrogation into the very nature of subjectivity, reality, longing, and a sense of belonging. Richard Chess reveals a person in a pained straddle of faith, longing for refuge in this vast universe, in “With Solomon Ibn Gabirol.” “Gifts,” by Faith Adiele, shines a two-year-old’s light on burgeoning authenticity and identification with others in the face of racial, religious, and economic difference. Meena Alexander’s lyric “Song of the Red Earth” carries us to the dust, the dissolution, of an irretrievable childhood identity. In “We Are All Colored,” Huston Diehl illuminates muddles of color-perception, as she recalls teaching ele mentary school in rural Virginia in 1970.

To flourish, authentically, in the larger social world—is it possible with all our messiness? Perhaps it is impossible without it. In “Surprises of the Self,” Martha Nussbaum examines the life and work of Donald Winnicott, a psychoanalyst for whom models of love, creativity, and good relationships necessarily pre suppose the acceptance of messiness and imperfection in one self and in others. When applied to society, Winnicott’s ideas have rich implications for expression and growth. In “Buried,” by Carol Edelstein, we find perfectionism posing a subterranean threat to wellness. Donald Morrill conjures creativity’s golden magic and its maddening limits in “You,There, Listening…”

Perhaps it is because of our inherent instability, with threats to our integrity coming from inside and out, that it is also in our natures to impose order on our experience whenever possible. We categorize, organize, filter in, and filter out information about ourselves and the world around us. Moreover, we reflect on our desires and beliefs and guide our actions in accordance with our reflections: we act for reasons. Certainly, we need to structure, in order to comprehend, the data of our experiences, and there is benefit to authorizing our actions through reflection and reasoned deliberation. Just as certainly, our restless minds need to break through the structures of understanding and the dictates of reason, to make leaps in growth and creativity. Well being may require the acceptance of ourselves as much in the ways we are irrational, as in the ways we are rational. “The Messy Self” is intended as a forum in which to highlight our self-complexities. Taken together, the writings herein analyze, accept, bemoan, resist, frown upon, and ultimately celebrate our essential messiness.

Jennifer Rosner

Northampton, Massachusetts

Spring 2006

NOTES

1. Jonathan Lear, Love and Its Place in Nature: A Philosophical Interpretation of Freudian Psychoanalysis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 148ff.

2. For a fascinating and comprehensive discussion of love, and its role in ethical thought, see Martha Nussbaum, Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Table of Contents

The Messy Self: An Introduction, Non-Fiction by Jennifer Rosner, guest editor

A Strange Disorder, Poetry by Diane Ackerman

My Tourette’s, Non-Fiction by Gayle Pemberton

Conservation, Fiction by Debra Spark

The Mommy at the Zoo, Poetry by Beth Ann Fennelly

Prologue to Psyche, Non-Fiction by Jane Crosthwaite

Psyche in Love, Drama by Wendy Wasserstein

Since You Came, Poetry by John O’Donohue

The Clause, Poetry by C.K. Williams

The Last Place on Earth, Non-Fiction by Patricia Foster

Facing North, Poetry by Mary Kinzie

The Fiction of Self and the Self of Fiction, Non-Fiction by Rebecca Goldstein

The Real Story, Non-Fiction by Liv Pertzoff

The Superficial Unity of the Mind, Non-Fiction by Sarah Buss

Kidding Ourselves, Non-Fiction by Steven Pinker

The Disappearance, Fiction by Ilan Stavans

With Solomon Ibn Gabriol, Poetry by Richard Chess Gifts, Fiction by Faith Adiele

Self-Portraits, Art by Lee Gordon

Song of the Red Earth, Poetry by Meena Alexander

We’re All Colored, Fiction by Huston Diehl

Winnicott on the Surprises of the Self, Non-Fiction by Martha Nussbaum

Buried, Poetry by Carol Edelstein

(You there, listening . . . ), Poetry by Donald Morrill

Contributors

Diane Ackerman is the author of twenty works of poetry and nonfiction, including most recently An Alchemy of Mind (prose) and Origami Bridges: Poems of Psychoanalysis and Fire.

Faith Adiele‘s account of being the first black Buddhist nun in Thailand, Meeting Faith, won the PEN Beyond Margins Award for Best Biography/Memoir of 2004. Her work has appeared in O, Essence, Ploughshares, Transition: An International Journal, Ms., Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, and numerous anthologies. Adiele resides in Pittsburgh, where she is Assistant Professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh. Currently, she is finishing a memoir about growing up Nigerian/ Nordic/American, which has inspired the PBS documentary My Journey Home.

Meena Alexander‘s volumes of poetry include Illiterate Heart (winner of a 2002 PEN Open Book Award) and Raw Silk, 2004. Her memoir Fault Lines (Publishers Weekly Choice, Best Books of 1993) was reissued in 2003 with a chapter “Lyric in a Time ofViolence.” She is the editor of the anthology Indian Love Poems (Knopf/Every man’s Library, 2005). She teaches at Hunter College and is Distinguished Professor of English at the Graduate Centre of the City University of New York.

Sarah Buss is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the University of Iowa. She is co-editor of Contours of Agency and has published numerous articles on autonomy, happiness, moral responsibility, weakness of will, and respect for persons.

Richard Chess has published two books of poetry, Tekiah and Chair in the Desert. His poems have appeared in several anthologies, including Telling and Remembering: A Century of American Jewish Poetry, as well as many journals. In 2002, he received the N. C. Board of Governors’ Award for Teaching Excellence. He has also been the recipient of UNCA’s Ruth and Leon Feldman Professor Award in 1999/2000 and the Distinguished Teacher in the Humanities Award in the same year. He directs the Center for Jewish Studies at UNCA and UNCAs Creative Writing Program. He is also on the MFA faculty of the Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College.

Jane F. Crosthwaite is a member of the Mount Holyoke College Religion Depart ment. Although her earliest work was on Emily Dickinson and the interface of religion and literature, her most recent work has focused on a range of Shaker studies. She has published articles and given numerous presentations on Shaker women, theology, and spirit drawings, and is currently completing a book with Christian Goodwillie on the theology and music of the first Shaker hymnal.

Huston Diehl is a Professor of English and Collegiate Fellow at the University of Iowa. She has published extensively on Renaissance drama and the religious and visual cultures of early modern England. Currently, she is completing a memoir, Dream Not of Other Worlds, about her experience teaching in a segregated “Negro” school in rural Virginia.

Carol Edelstein is a poet, fiction writer, and essayist whose work has appeared in numerous literary magazines and anthologies. Her second book of poems, The Disappearing Letters, won the 2005 Perugia Press Intro Award.

Beth Ann Fennelly is the recipient of a 2003 National Endowment for the Arts Award. Her poems have been anthologized in The Pushcart Prize 2001, The Penguin Book of Sonnets, Poets of the New Century, and The Best American Poetry 1996 and 2005. Her first book, Open House, published by Zoo Press, won the 2001 Kenyon Review Prize for a First Book and the GLCA New Writers Award. Her second book, Tender Hooks, was published by W.W Norton in the spring of 2004. A book of nonfiction, Great With Child, will be published by Norton in 2006. She is an Assistant Professor at the University of Mississippi, and lives in Oxford, MS.

Patricia Foster is the author of All The Lost Girls (memoir) and Just Beneath My Skin (essays), editor of Minding The Body and Sister To Sister and co-editor of The Healing Circle. She is a professor in the MFA Program in Nonfiction at the University of Iowa.

Rebecca Goldstein is the author of five novels, including The Mind-Body Problem, The Late Summer Passion of a Woman of Mind, The Dark Sister, Mazel, and Properties of Light, as well as a collection of short stories, Strange Attractors. She is also the author of Incompleteness: The Proof and Paradox of Kurt Gödel, and the forthcoming Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity. The recipient of numerous prizes for fiction and scholarship, she became a Mac Arthur Fellow in 1995. Lee Gordon is an alumnus of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst (1979). Upon completion of his MFA at Rutgers (1982), he was in the first museum show to explore the idea of a homosexual sensibility in contemporary art at The New Museum, NYC, where his work was called “diabolically intelligent.” Since then he has been in hundreds of exhibitions including solo shows in New York City, Paris, Chicago, New Orleans and The University of California in Santa Barbara.

Mary Kinzie is the author of Drift (poems) and of A Poet’s Guide to Poetry. “Facing North” is part of a verse meditation to be called The Poems I Am Not Writing. She is the literary executor of the American poet Louise Bogan.

Donald Morrill is the author of three books of nonfiction, The Untouched Minutes (winner of the River Teeth Literary Non fiction Award), Sounding for Cool and A Stranger’s Neighborhood, as well as two volumes of poetry, At the Bottom of the Sky and With Your Back to Half the Day. Currently, he is a visiting professor in the Nonfiction Writing Program at the University of Iowa and poetry editor of Tampa Review.

Martha Nussbaum is Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics at the University of Chicago, appointed in the Philosophy Department, Law School, and Divinity School. Her most recent books are Hiding From Humanity: Disgust, Shame, and the Law (2004), and Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership (2006).

John O’Donohue is an Irish poet and philosopher who lives in the solitude of a cottage in the West of Ireland and speaks Gaelic as his native language. He has degrees in philosophy, English literature and was awarded a Ph.D in philosophical theology from the University of Tubingen in 1990. His books include Anam Cara, Eternal Echoes, and Beauty.

Gayle Pemberton is the author of The Hottest Water in Chicago: Notes of a Native Daughter and the forthcoming The Road to Gravure: Black Women and American Cinema. She is the author of a number of creative nonfiction essays on American culture and African American life. She is Professor of English, African American Studies, and American Studies at Wesleyan University.

Liv Pertzoff writes short fiction and essays. She lives in Williamsburg, MA.

Steven Pinker is Johnstone Professor of Psychology at Harvard University, and author of The Language Instinct, How the Mind Works, Words and Rules, and The Blank Slate.

Jennifer Rosner, guest editor of this issue, holds a Ph.D. in Philosophy from Stanford University. She is author of several articles on the nature of the self and human agency. Currently, she is writing a memoir about deafness in her family, which she traces back from the 1800s to the present day.

Debra Spark is author of the novels Coconuts for the Saint (Faber&Faber, Avon) and The Ghost of Bridgetown (Graywolf) and editor of the anthology Twenty Under Thirty: Best Stories by Americas New Young Writers (Scribners). Her most recent book is Curious Attractions: Essays on Fiction Writing (University of Michigan Press).

Ilan Stavans is Lewis-Sebring Professor in Latin American and Latino Culture and Five College-40th Anniversary Professor at Amherst College. His most recent books are Dictionary Days (Graywolf) and Lengua Fresca (Houghton Mifflin). The story in this issue is included in The Disappearance: A Novella and Stories, to be published in August by Northwestern University Press. A feature movie based on the novella will be released in the fall.

Wendy Wasserstein, the Pulitzer-Prize winning playwright who passed away in 2006, is the author of The Heidi Chronicles; The Sisters Rosensweig; Bachelor Girls; An American Daughter; Seven One-Act Plays; Uncommon Women and Others; and Shiksa Goddess.

C. K. Williams is the author of nine books of poetry, the most recent of which, The Singing, won the National Book Award for 2003. His previous book, Repair, was awarded the 2000 Pulitzer Prize, and his collection Flesh and Blood received the National Book Critics Circle Award. His Collected Poems will appear in 2006. He has published translations of Sophocles’ Women of Trachis, Euripides’ Bacchae, and poems of Francis Ponge, among others. His book of essays, Poetry and Consciousness, appeared in 1998, and a memoir, Misgivings, in 2000. He teaches in the Writing Program at Princeton University.