10+ Questions for Ahmad Almallah

What does it mean to be a poet, another “Homer”

going home? Trying to find one?

Is it time to prepare?

—from “Loose Strings,” Volume 65, Issue 4 (Winter 2024)

What role does language play in resisting colonialism and precipitating and precipitating? How does your piece engage with this question?

Language is the steppingstone to any movement for liberation. Colonialism understands this reality to the extent of paranoia. After almost a year and a half of genocide in Gaza and Palestine, all these words—genocide, Gaza, and Palestine – instead of becoming self-evident, are now being censored. People who use them are being silenced and harassed. Poetry works to reignite language and remind it of its real function. Poetry anchors language as truth and saves it from becoming a tool for deadly speech, and even a tool for spreading lies and covering the facts. Any poetry that plays into the usual tricks of language is bound to lose force over time. Ultimately, poetry resists all forms officialdom that want language to represent rather than reinvent and imagine new ways to be and witness. In my piece, I refuse to be rewritten or translated. The poem is unapologetically two things at the same time, and the Arabic ends the poem like a sigh, an exhale which doesn’t need to or cannot possibly be translated.

Are there cultural or literary traditions from Palestine that particularly inspire your work? How does community—whether local or diasporic—influence your work?

I wrote a line in the poem “Bitter English” that I live by “I owe everything to one place that owns me, not here, where what I owe I do not own.” Aside from this essential connection to Palestine, I find infinite inspiration from Ghassan Kanafani and Naji Al-Ali…two artists who never settled for being a representation, and their art was the truth that placed them beyond time. Any artist who’s trying to play or use the moment of this genocide to their own advantage will disappear from existence. The future is a witness, and it will only remember those who remained true to Palestine above all else.

I write in conversation with other poets, and Palestine belongs to the rich Arabic Poetic tradition. For me Arabic is the first spark, the beginning of my fascination with language as a child. And although I write in English, I am driven by Arabic sounds, the voices of Imru’ al-Qays, Abu Tammam, al-Mutanabbi and others. Beyond Arabic, one of my most intimate companions is Emily Dickinson. More recently, in the past couple of years, I have befriended Lorca, especially when I found myself taking refuge in is beautiful Granada when I was getting harassed and persecuted in Philadelphia and home in Palestine was beyond reach.

How do you envision the relationship between art and activism in your practice? What responsibility, if any, do you feel as a writer to document the lived experiences and resistance of Palestinians?

Activism is activism. I despise the artist who pretends that only through their art they will liberate Palestine. We must fight for Palestine outside the poem as well, in every facet of our daily lives. Hit the streets. Be part of the actions and protests. Do all you can to be part of the change …and that’s the least we could do as witnesses of Israeli apartheid and genocide.

What challenges do you face when writing about Gaza for international audiences? How, if at all, do you address these challenges in your work?

The main challenge is to not be sucked into the western and American publishing industry that pretends to give space for voices from Palestine and Gaza, as some sort of propaganda for the “liberal” and “open” society that is the West…while at the same time it will take no real steps to stop the genocide. If we play into this and make names for ourselves as artists here, then we have betrayed our cause and our people.

In what ways have you seen grief and anger act as an impetus for change? How have these emotions manifested (or served as powerful drivers) in your own creative process?

Grief and anger made all my poetry collections so far. Anger is a powerful rebellion against silence, but it does not sustain you. You eventually burn out, only to settle in grief…which unlike anger has so many manifestations and gives way to truth in language without pretense or performance.

Who are the artists, writers, and activists you currently follow or admire? What stories or voices from Gaza do you think the world needs to hear more of? What barriers do you believe impede these stories/voices from being heard?

Every story from Gaza is a testimony to a people fighting for a just cause. Every individual in Gaza is a poet that is not in need of a publisher or a venue. To be able to speak against unimaginable violence is in itself a testimony to the power of the human against all massacres and violence. This is the true power of the word, and those words pronounced under the most evil waged upon a people during our time is nothing short of a miracle…a miracle that only the people of Gaza can perform and put us all to shame and awe. Every person in Gaza is the ultimate artist because they have managed to live with the impossible. There is no greater art than what the people of Gaza have invented for all humanity.

How do you nurture yourself and practice self-care throughout the writing process? What role has your community played in helping you endure during this profoundly challenging time?

On one hand, I have lost so many friends because they have been unable or refuse to acknowledge the evil of the Israeli state and its supporters in this genocide, but on the other, I have met new friends in the protests, actions, and gatherings for Gaza. They are now my community and the subject of my admiration. Anyone who accepts normalizing the genocide in Gaza and can go about their lives “business as usual” is no longer worthy of my respect or friendship.

What actions should writers and artists from around the world take to support Palestinian writers? How can they effectively create and hold space for them?

I wish I could answer this question without so much bitterness. Many of the organizations offering support to me as a Palestinian demand that I alter my position, soften it, and betray myself. I think the next step for the struggle for Palestine in the country is for us to create networks of support for the people speaking truth about Palestine and exposing all the complicit, corrupt, and racist systems of hegemony. All the students who have been harassed and their homes raided need us to have their backs and offer them support against isolation and loneliness. If we need supporters of Palestine and Gaza to be strong, we must create the networks to support them and sustain their struggle.

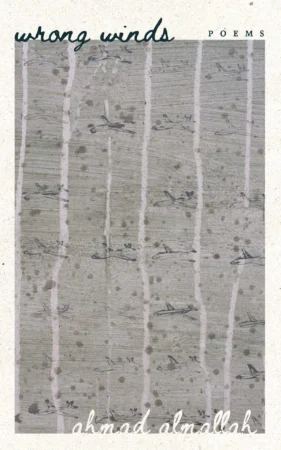

Pre-order Ahmad’s forthcoming book wrong winds, coming March 2025 from fonograf editions

AHMAD ALMALLAH is a poet from Palestine. He currently lives in Philadelphia where he is an artist-in-residence in Creative Writing at the University of Pennsylvania. His poems have been translated into Arabic, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Telugu. He is the author of Bitter English (Phoenix Poets Series, University of Chicago Press, 2019) and Border Wisdom (Winter Editions, 2023). His new collection of poems, Wrong Winds, is available to preorder from Fonograf Editions and will be published on March 18, 2025.