Among the Pressing Wild: Cynthia Huntington’s Civil Twilight

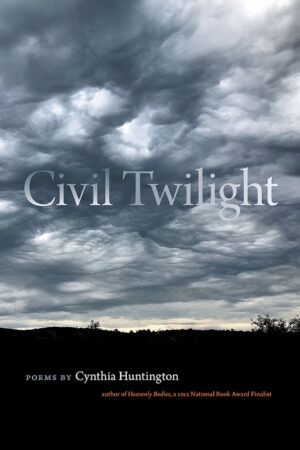

By naming her collection Civil Twilight, Cynthia Huntington situates us in a narrow interval—the few minutes when the sun hovers zero to six degrees below the horizon. Any higher and it’s daytime. One degree lower is twilight of a different kind.

Concerned as it is with precision, however, Huntington’s title also creates ambiguity. Civil twilight occurs twice daily, immediately after sunset and just prior to sunrise. Are we entering a long darkness? Watching for morning? I don’t know—and I don’t know that it matters. Rather than orienting us to what’s approaching, Huntington calls us into a transitory space.

Here’s the thing about transience and liminality: they’re often uncomfortable. We want clarity of understanding. Clarity of direction. We want to keep moving, as do the people in Huntington’s poems. The woman who leaves yoga class early. The mourner who leaves the other mourners to buy groceries. The speaker who “drove for hours in a fugue” even as “the road kept appearing / and disappearing ahead.” Plunged into the silence of savasana or the murkiness of grief, these people hurry away because action can feel like an antidote to unsettledness.

That’s not always the case, Huntington reminds us. Her speaker, while walking, fishes a can from the roadside brush

as if I could save something from all this mess,

but it’s breaking up, breaking down; mud

and the soup of time drip from the can,

shot through with holes, someone’s target practice.

The trouble with time is we only see part of it.

These lines are from “Will Spring Ever Come to the North Country”—a query with an answer so obvious, Huntington omits the question mark. I’ve lived in New England most of my life and every February I’ve said something similar. I know about Earth’s tilt and orbital path. I know each past winter has given way to not-winter. And yet something in me still believes the freeze to be interminable. The trouble with time is we only see part of it—and only through the lens of our own living.

It’s the same for Huntington’s speaker, who, in “Late Tenement, 1974,” sketches the evolution of an apartment building: stairwells opened to comply with codes, a cramped bathroom that improves on previous hallway toilets that were themselves improvements on courtyard privies. We might assume she’s lauding progress, but the poem ends this way:

I was a stranger there and young.

That world, that time, was past, already done,

new city coming into time, all new. But there it stood,

still tenanted and full, and I was there

just living there, though only passing through.

In naming “that time … already done,” the speaker refers not to the era of tenements but her own tenure in the city. She is passing through, observant but uninvested, and solitary.

That sense of aloneness permeates the collection. Consider this section of “After a Line by Tranströmer:”

Turn down the lights

and let dusk fill the window glass,

pour whiskey in a cup and drink

in honor of the day: so long,

nice knowing/not-knowing

you. The low sky gleams.

Huntington isn’t often instructional, so it’s significant that she specifies how we should meet the twilight: with whiskey, with acceptance of how much we cannot know. Not-knowing in the sense of uncertainty but also unfamiliarity. The poem concludes:

A fluttering like birds,

the heat comes up in the furnace.

Then footsteps, someone walking on my ceiling,

someone living in the air above.

I'm living in this air below,

alone, but nearby.

Hearing them, so not alone.

But alone. The glass is dark now

and headlights flick on in the sky,

no, they're winding down the hill.

Behind each light a face

staring into the dark

out of the other dark.

Alone, but nearby; not alone, but alone. This isn’t equivocation—it’s nuance. There is a measure of comfort in the nearness of others and there are ways in which a person can never be near enough.

We see this concern again in “Jackass Angels.” The speaker, on a long car trip, stops for a meal at a bar and is joined by two men she believes are heavenly beings. They eat off her plate and put their beers on her bill, and bum a few cigarettes as they part in the parking lot.

I used to say I'd go anywhere any time

any angel asked, but you don't have to

take them so seriously, you don't have to follow them

into the night, or wrestle them for a blessing,

just laugh and say not this time, and they'll let you go.

And sometimes they'll tell you their names:

Tom. Brian.

These lines reference the Hebrew biblical story of Jacob, who wrestles God, disguised as an angel, until dawn—civil twilight—at which point God renames him and Jacob, now called Israel, marvels that he’s seen God’s face. The grappling and renaming and seeing suggest deep intimacy—a kind of communion we needn’t always pursue. Solitude, Huntington suggests, isn’t failure. To be known even briefly and incompletely is no small thing.

In addition to biblical literature, Huntington engages with the work of Tomas Tranströmer, Hart Crane, Barbara Guest, Fernando Pessoa, and Robinson Jeffers, among others. Her willingness to converse with a wide literary tradition well as her attention to ancient and American history give the collection a gravity that can also be felt in its forms. Huntington favors prose poems, lyric essays, and long- or single-stanza free verse—dense text that demands careful reading. Her tone, while warm and sometimes witty, is also reserved. These are quiet poems that mingle the philosophical with the mundane. Take “River Road,” in which the speaker lists the names of God alongside kinds of train cars, noticing “[h]ow the river / carves a shore, a place of pause where woods stand back, / a swath of light among the pressing wild.”

That image, one of comfort, leads into a final line: “Dread this sun now quickening.” Earlier in the poem, the speaker references one of the biblical psalms, suggesting that we can read this poem—and perhaps the full collection—as a lyric in the psalmic tradition: a song of hope and lament. Huntington is compelled to identify both the wildness and the place of pause. To praise the luminosity of a quickening, burning sun.

ABBIE KIEFER is the author of Certain Shelter (June Road Press, 2024), named a 2025 Julia Ward Howe Award Notable Book. Her work is forthcoming or has appeared in The Atlantic, Copper Nickel, Image, Pleiades, Ploughshares, The Southern Review, and other places. She lives in New Hampshire. Find her online at abbiekieferpoet.com.