No Time to Panic

Back in the mid-eighties, for those of us who studied the dark arts of ninja theory in the Parisian dojos of Derrida and Deleuze, S/Z by Roland Barthes was a seminal scripture. One of many keys it offered was its lesson that books don’t have to read from beginning to end—that, instead, they’re more like the subway, with dozens of ways in and out. Readers should use them to get where they need to go.

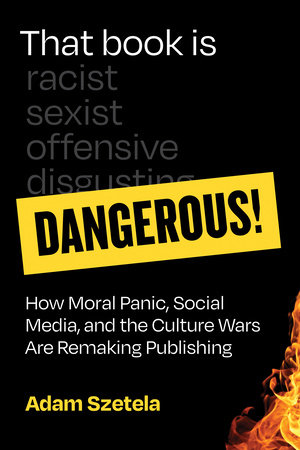

Yet books are also material objects, and authors, together with their publishers, craft them carefully, hoping to shape our response. As such, in responding to a work like Adam Szetela’s That Book Is Dangerous! How Moral Panic, Social Media, and the Culture Wars Are Remaking Publishing, reviewers would be well advised to adopt an extra, meta level of care, given how much of the book is itself an analysis of book reviewing and reviewers. As its online summary avers,

Szetela investigates how well-intentioned and often successful efforts to diversify American literature have also produced serious problems for literary freedom […] What he finds is unsettling: mandatory sensitivity reads; morality clauses in author contracts; even censorship of “dangerous” books in the name of antiracism, feminism, and other forms of social justice [… R]ather than genuinely address the economic inequities of literary production, this current moral crusade over literature serves only to entrench the status quo. “While the right is remaking the world in its image,” he writes, “the left is standing in a circular firing squad.”

So where to begin? Readers of the Mass Review, I predict, will find much to argue with in Szetela’s work; they may also wish to hear more about some things and would likely have preferred less discussion of others. I assume this, because that’s how I responded. I do worry, however, that his book-length essay, where each of its chapters builds a different angle on what the author refers to as the “Sensitivity Era,” might be accused of fighting the last war, rather than confronting the enemy we now face. If sensitivity was an era, isn’t it over? Isn’t cruelty the order of the day?

The best way to read Szetela’s book, I believe, is backwards. So that’s what I plan to do. (Not word-by-word, obviously, though you might catch some typos that way.) Reading backwards does begin with the blurbs, and Szetela’s are more important and more impressive than most. His endorsers include a former president of the ACLU and chaired professor of law from NYU, a chaired professor of psychology from Harvard, a Pulitzer prize-winning author of fiction, an NYU professor of sociology, and a Dartmouth professor of English and American Studies. Interdisciplinary breadth seems nearly as important as prestige here, though the key to blurbage is always the cultural capital of names it lends to a project. All but one blurber identifies censorship as the book’s subject; the other describes our current moment as the “wreckage” the book will help us crawl out from. This apocalyptic register is reached by the others as well: “modern-day book-burning” and “madness,” for example, are mentioned. The novelist urges you to read this book “[i]f you believe in literature and wish it to have a future.”

I also spent a good bit of time with Szetela’s index, mainly to satisfy my curiosity about something I found jarring, given both the book’s title and its blurbs (not to mention the summary on inside flap of its dust jacket). I quickly counted and roughly categorized everything the index lists in italics. Forty-six different titles of YA literature and a somewhat smaller number written for adults, thirty-five, are given; the latter number is about the same as that of literary critical titles. (Smaller numbers of titles reference magazines, academic journals, newspapers, or works of visual culture, such as movies or comic books.) What I find odd, therefore, and suspect intentional, is that nowhere—in any of the blurbs, in the summary, or, for that matter, in the title of the book or its chapters—do you find YA lit mentioned. This omission does seem significant: discussions of reader responses to young adult literature dominate book’s first two chapters (and there are only four chapters). When you open a can labeled as Italian tomatoes, you’re not expecting the contents to be ketchup.

The indexical breakdown of authors and titles is equally informative. Here YA titles dominate: Blood Heir is mentioned on 6 separate pages, both American Heart and A Birthday Cake for George Washington on 5; Seuss books are discussed on 7 and the Harry Potter series on 5. Of literary classics, commentary on Miller’s The Crucible occurs on 6 pages, on Orwell’s 1984 across 7, and there are mentions of Twain and Shakespeare on 7 pages as well. Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 tops the list, named on 10 different pages; it is also the only book broken down into subcategories.

Next up in my reverse read: Szetela’s over fifty pages of end notes. I won’t say much about them, though I will remind readers that the pages of a book cost money; as such, the decision of the author and his publishers to dedicate nearly 20% of the text to its bibliographic buttressing was no idle choice—it is a manifestation of scholarly work. Szetela’s notes, I should add, also tend to be short: nearly all supply references, not annotations, digressions, or qualifications.

About seven and a half pages of acknowledgments precede the notes. This section provides readers with an intellectual autobiography as well as a further assemblage of supporting scholars. One of the book’s most frequently repeated terms is “lived experience,” so it is not unimportant that these pages list the author’s predilections for mixed martial arts, bodybuilding, skateboarding, mosh pits, rap music, and stand-up comedy as well as his blue-collar upbringing—along with his Cornell pedigree and dissertation advisor, who gets called a “batshit crazy woke feminist” (not by Szetela [198]). In the interests of transparency, I should also note that Szetela’s undergrad degree was from UMass, and that the scholar credited with convincing him to jettison his business major was for many years an editor at MR. Nor is it inconsequential that these acknowledgements follow the text proper, rather than preceding it—an order reversed here.

Time to dig into Szetela’s arguments directly. The final pages of his final chapter, in a final section titled “The Path Out of the Sensivity Era,” cites a critique of PC behavior by Stuart Hall: “Our enemies are bad enough; God save us from our friends” (196). This quote, Szetela comments, “could be the epigraph to That Book is Dangerous!” By the end of the book, readers will be well aware of who these so-called friends are: the self-proclaimed progressives who have organized social media campaigns against “Brooke Nelson, Jessica Cluess, Kosoko Jackson, Amélie Wen Zhao, Keira Drake, Laura Moriarty, Laurie Forest, Ramin Ganeshram, Vanessa Brantley-Newton, Andrea Davis Pickney, Dav Pilkey, Emily Jenkins, Sophie Blackall, Alexandra Duncan, E.E. Charlton-Trujillo,” as well as, Szetela alleges, “countless others” (195). Some or all of these names may be familiar to readers of MR, but since most weren’t familiar to me, I’ll add that they are the authors of YA novels and/or recent targets of cancel culture—the victims, according to Szetela, of a moral panic.

Only in Szetala’s final chapter, unless I’ve missed it elsewhere, is there an explicit argument about the relationship between the YA literary world and publishing as a whole. There, after discussing a 2011 report in Adweek about a morality clause inserted in HarperCollins contracts, Szetala does comment that, “sensitivity readers, morality clauses, and other interventions have spread from literature written for children and young adults to literature written for adults,” and he then goes on to document this claim (184). Moral panics about children no doubt date back to the invention of childhood, but whether the concerns of YA publishing now drive decision-making elsewhere in the industry seems an open question, and one well worth developing further. In an observation that must have written long before the second coming of Trump, Szetela cautions progressives against “championing morality clauses, sensitivity readers, and other interventions that give publishers even tighter control over their authors” (186). In a now sadly prescient observation, he also notes,

[C]onservatives might not want to read a children’s book that celebrates Black Lives Matter, a YA novel that humanizes a gay teenager, or an adult memoir written by an antifa protester […] As Donald Trump put it in an April 2021 statement about “woke cancel culture,” “We can play the game better than them” (186-7).

Today, one must add picture books celebrating Palestinian culture to this list. The path out for progressives, Szetela argues, requires them to refuse to remain silent; they must speak out when degradation ceremonies are performed by other progressives—surely Szetela’s goal in writing his book.

Szetela’s third chapter, “The Political Economy of the Sensitivity Era,” was the section of the book I was anticipating most. Last June 14, Becky Tuch’s always essential Lit Mag News! began with a query: “Q: Is class a feature of marginalization and underrepresentation in lit mags? ‘Do the voices of the poor not bear mention?’” She then noted that she had been reading an ARC of Szetela’s book and was particularly struck by its discussion of how class identity seems invisible to publishers today. As does Szetela, Tuch went on to cite an assortment of lit mags who encourage submission by authors defined according to various identities, yet where, in each, class does go missing. Seems like an easy thing to fix, and I would encourage MR to do so.

Szetela’s political economy chapter begins with the example of Jason Allen, a writer who has been employed as a cashier, bartender, and construction worker, and at least once, as a pool boy for another writer in Bridgehampton, New York. Szetela also argues that, as a marker of identity, class is not equivalent to others: whereas BIPOC, gender, and other identities could potentially coexist in equality, any society with economic classes is based by definition on inequality. Within communities of gender, color, et al., Szetela reminds us, class differences persist and are often determinative.

Szetela does some controversial work of his own in documenting the economic privilege of those he calls “moral entrepreneurs,” the authors and publishers who profit from the campaigns of “moral panic” that mobilize “degradation ceremonies.” At several points in the book, Szetela takes on Philip Nel, the author of Was the Cat in the Hat Black? (128), suggesting, for example, that it seems easier for Nel to confess “his white male, straight, cisgender privilege” than to name the economic benefits of class (128). He also argues that, for Dhonielle Clayton, board chair for the non-profit We Need Diverse Books, “There is no distinction between [her] personal financial interests and the moral crusade over literature” (137). Ibram X. Kendi is a target as well: Szetela lists the eight publications on antiracism that Kendi has published since 2019 and then comments: “In all seriousness, Kendi should title his next book How to Be a Capitalist” (141). Readers should also note that, published by MIT Press, sales and distribution of That Book is Dangerous is handled by Penguin Random House—a conglomerate that comes in for repeated, sustained criticism in its pages.

One has to wonder, though, whether Szetela’s critique is likely to bring the left to a moment of self-reflection, or whether it will ultimately provide simply more fodder for the right. One also needs to ask whether Szetela, in his takedowns of Nel, Clayton, Kendi, et al., may be instigating a moral panic of his own. On the left, we are very familiar with moments in US history where progressive victories were won and then followed by concerted efforts at counter-reformation. Polemics against “tenured radicals” and Bloomian defenses of the classics have also resurfaced regularly on bestseller lists—surely such crusades are not company that Szetela would care to keep. Today, all work in the humanities, if not the very idea of higher education itself, is under attack; another screed calling out academia as elite culture will likely have many conservative fans. In any case, my graduate students today, whether aspiring literature professors or writers, are generally sanguine about their chances of joining this so-called elite. More likely they’ll struggle for years, working for barely subsistence wages, before landing anything that puts even a temporary end to their precarity. The star system in academia and publishing, though of lesser magnitude, is organized like neoliberal capital elsewhere.

In his second chapter, on “The Behavior of the Sensitivity Era,” Szetela develops the connections between the social-media mobbing of today and the history and sociology of earlier moral panics. This chapter leans heavily on literary classics such as Fahrenheit 451 and Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery”; Szetela reminds us that when Jackson’s story, where “a village randomly stones one of its own to death,” “hundreds of readers canceled their New Yorker subscriptions or wrote angry letters (101). He then comments, “Seventy years later, ‘The Lottery’ should be read by anyone trying to understand the social dynamics of literary culture today” (101). This chapter also introduces another important historical parallel: the moral crusade against comic books in the fifties. Though puritanical zealots have certainly taken up other causes in other moments (think, for example, of the temperance campaigns against alcohol and masturbation), I for one was happy to hear Szetela explain why, when I was a kid, my parents sent me to a Great Books class but didn’t let me buy comic books.

As noted above, I hope this reverse read of Szetela’s pages will encourage progressives to take his crusade seriously and take their own stands on the behavior and issues he describes. Among the hundreds of scholars Szetela cites, a quote from Todd Gitlin stands out. In the late sixties, Gitlin observes, the left was “marching on the English department while the right took the White House.” Szetela adds, “Five decades later, the left has won all the English departments. Yet, at a moment when the right controls the majority of state houses, the majority of state senates, the majority of state houses, the US Senate, the US House of Representatives, the Supreme Court, and the Oval Office, progressives still have their eyes focused on literature” (152). Sounds like a scene from a Hollywood Western, doesn’t it? The path of liberation suddenly reveals the university to be a box canyon, a trap leaving us open to the enemies’ guns.

If there is a central, crucial axiom that Szetela wishes to attack, it is offered in a Kirkus Review comment cited early in his first chapter, on “The Ideas of the Sensitivity Era” (17). There it is claimed “there is no substitute for lived experience.” Though Szetela does not, one might easily contest this statement by rewriting it, noting, for example, that “there is no substitute for imagination”—or for “empathy,” “good writing,” or “talent.” One might also remind readers that—so long as oxymoronic concoctions like “autofiction” or “creative nonfiction” are excluded—by definition, in fiction there is no such thing as “lived experience.” That’s why we call it fiction.

In early 2020, in the pre-COVID era, I heard John Sayles present his novel Yellow Earth at a book launch event in Amherst. Given its setting—a shale oil boomtown on a reservation—it wasn’t hard to predict that Sayles would be asked how, as a white writer, he is able to create Native American characters. His answer was simple: “You just have to get it right.”

Arguably Sayles offers the only possible answer, even if what makes readers believe make-believe stories is itself anything but simple. Surely many readers endorse narratives because they reinforce pre-existing stereotypes. Others, e.g. our readers, find value in stories that push back against this sort of story and thereby open up a wider, more inclusive world. What any given case represents is subject to debate, and there are rules for reasonable discussion, familiar since at least Milton’s Areopagitica or the Age of Enlightenment.

As Szetela argues, we should have that debate and quit with the circular firing squads.

We need to get this right.

JIM HICKS is former Executive Editor of the Massachusetts Review