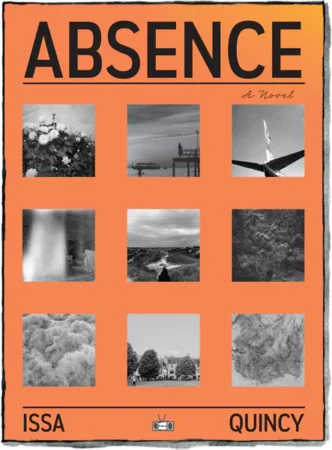

A Review of Issa Quincy’s Absence

In Issa Quincy’s debut novel, Absence, the unnamed narrator mythologizes a series of figures

that he directly or indirectly encounters, including a disgraced teacher and the student he seduced and forever changed; a lonely bus driver in Boston; a disabled landlord who mourns the lesbian aunt his family abandoned; and other strangely compelling people.

Each of these episodes stages the revelation of a life. The subject of or a witness to this life offers

it up in language—tells the story—to the narrator, who takes up the pose and position of

attentive listener. Almost all of the episodes are bookended by the death of one or more of their

subjects, so that they can be read as chronicles that guard against the subjects’ oblivion, that is,

their being forgotten. The entire novel is structured by the death of the narrator’s parents, who

are similarly mythologized and recur throughout as storytellers in their own right, or as points of

connection to the other protagonists—through, for example, a poem that the narrator’s mother

often recited to him when a child and which he later, repeatedly, finds traces of in others’

personal effects; or a photograph of his adolescent self taken at his godfather’s funeral that his

father carried with him around the world.

The prose is consistently and incredibly beautiful. The truest iteration of the text would be in the

form of a live reading to a rapt audience. Verses and images that travel in and reappear through

time and space are instructive signs for how the novel approaches language. The lines are so

rhythmic and resonant (“the tremor of a true and deep-rooted spirit”; “to suffuse that slowly

appearing gap”) that they echo in the reader’s mind, and later return, unbidden. Each word is

precise and carefully chosen so that the text rewards rereading: first for the story, then for its

craft.

Early in the novel, the narrator describes the painting Winter Landscape with Ice Skaters by

Hendrick Avercamp, and says that it is “the close detailing of the variance of life,” with “death,

pleasure, ecstasy, frivolity, poverty, and secrecy … all perceived from a heightened position.” He

posits that, “what is presented is the sight of the intangible spectator that sees what is in front of

him, recognizes everything, and curtails judgment of anything.” It appears, then, that the novel is

an attempt to achieve with words what Avercamp achieves with brush and color. Here is a “close

detailing of the variance of life” from the perspective of a narrator who “curtails his judgment of

anything.”

Though the narrator is not completely effaced, he is certainly an “intangible spectator,” or rather,

an intangible listener. We have only a vague sense of his age, occupation, and motivations. He

listens to the stories that others have told him and reiterates them to the reader. When he offers

his perspective or emotional reaction, it is usually one of stupefaction, a being dazed by the story

told, unable to respond because the intensity of the story itself forecloses the possibility of an

adequate or meaningful response. He also need not respond because the storyteller does not

require his feedback. Rather, they are simply grateful for his listening ear. Sharing, of himself, only his dazed reaction, the narrator has the room relay at length everything that he is told,

including all manner of diversions, because everything matters, and all of it is encompassed in

“the variance of life.”

Each word is precise and carefully chosen so that the text rewards rereading: first for the story, then for its craft.

In a long episode on the narrator’s godfather, Max, the novel most clearly articulates its method

of showing singular hearts and the wider, infinite world through the threading together of

different, connected stories. Prompted by the photograph from Max’s funeral that his father

loved, the narrator, who never knew Max, goes in search of his life story. He meets Margaret,

Max’s family friend, and she tells him about Max’s childhood, his art, and his continuously

interrupted becoming. She tells of her friendship with his mother, Sarah, the trajectory of Sarah’s

own life, that of his father, Adam, and of his brother, Patrick. Sarah’s parents and Adam’s

parents, too, are evoked. The racist attack against Max’s employer, a Black magazine editor, is

also integral to the story. As is Max’s journey to Thailand, and the experiences he recorded in a

journal of his time in its forests. One gets the sense reading this episode that each character who

figures is a portal to a new, different story. And in each portal that one opens and enters, one

finds suffering. Not constantly, but eventually. Eventually, there is sickness, eventually there is

betrayal, eventually madness, eventually poverty, eventually loneliness. But the universality of

this suffering, and its role as connective tissue between people and the fabric of their storytelling,

confers beauty onto it. The story of Max and his family is a story of people who were basically

doomed by the horrific histories of their ancestors to live lives of unfulfillment. But even in these

thwarted lives, they were witnessed, remembered, and loved—by Margaret, by the narrator’s

father, by the narrator himself.

Notwithstanding the moral ambivalence of some of its characters, Absence is a deeply ethical

novel. It is, before anything else, the expression of an ethic: a commitment to “the unseen and the

unheard,” to people whose stories are usually and otherwise untold. This much is made explicit

in the second chapter, through the narrator’s witnessing of a bus driver whose chief complaint is

her invisibility, and who, because of this novel, is no longer unheeded. The unnamed, unseen,

and rarely heard narrator seems to be taking on the erstwhile absence of these abandoned people

so that they might become present. The narrator (and Quincy) seem to be wagering that this

narratorial absence will allow their subjects to come into focus and be seen clearly, fully. And

they are largely correct.

Because of this close attention to diverse figures, Absence spans decades and continents with

ease. It captures moments in history from the Algerian War of Independence to the degradation

of working-class life in postwar England, and it does all this in 160 pages. It is a small book, and

in this way it is of the twenty-first century, but its spirit is older, belonging to the long novels of

the nineteenth century, with their far-reaching, world-encompassing ambitions. By telling these

particular stories through these particular figures, the novel reveals that every story is a frame

story, all narrative is recursive, and mise en abyme is as legitimate a method as social realism in

revealing the wideness of the world. In this way, the novel departs from Avercamp’s model and

finds a model, instead, perhaps, in Borges’s aleph, the point through which all things can be

seen, not because of a high vantage, but because it is refractive, kaleidoscopic.

There is one question concerning the novel’s range, that remains, however, and it returns us one

final time to Avercamp. Does Absence as it praises the winter landscape for doing, show “death, pleasure, ecstasy, frivolity, poverty, and secrecy”? To be sure, there is death, there is poverty,

there is secrecy, but I did not encounter much pleasure or ecstasy or frivolity. Most of the

episodes are portraits of lives not very well lived, and where one finds some sense of frolic

alongside tragedy, the telling is primarily tragic, and does not live much in other modes. But

perhaps the novel seeks only to represent what is tragic, and I am overtaxing its brief allusion to

the winter landscape. Its other important allusion is to a verse that begins with the lines, “He is at

peace — this wretched man — / At peace, or will be soon” (from a poem by Oscar Wilde,

unattributed in the text), and this verse, with its emphasis on wretchedness in life and peace in

death, might better serve as evidence of the novel’s goals. Still, even if this were the case, it

would probably be a more moving text, its tragedy more deeply felt, if it were counterbalanced

by moments of relief.

Likewise, the novel might have acknowledged its artifice once or twice. Many of the stories the

narrator hears and reports are arriving at him a few degrees separated from firsthand experience,

but they are written with a level of detail that would imply that each person involved in the

retelling is gifted with immense powers of both recall and oration, a situation which is unlikely.

The narrator, then, is clearly embellishing, erring, empathizing, imagining (and what beautiful

empathy it is, what impressive imagining), but there is no winking mention of this artifice, no

levity around it. The narrator is obviously omniscient, but the novel disavows his status as author

and creator, and identifies him only as a faithful listener and recorder. This feels like a missed

opportunity. To acknowledge the narrator’s creative act, to present him both as a faithful listener

and a reporter using his poetic license, would have established between the reader and narrator

the same complicité we find between the narrator and his interlocutors.

Still, there are advantages to this disappearing act. The narrator’s absence—the absence,

therefore of his intention, his creation, his remembering, his exaggerating, his

poeticizing—makes it possible for the novel to achieve the incredible feat of feeling true and

based on the author’s real-life encounters and at the same time, further-reaching than lived

experience and capacious in the way that the best fiction is. Its characters have a life and

resonance beyond the intrigue of their possible real-life counterparts. Absence is representative

of fiction at its most human and its most comprehensive. It is full of imaginative empathy and

marked by its breadth, its multivocality, and its truth. It is a novel that views storytelling as

sacred, as the key to revealing connections between people that are not always or easily apparent.

It is an intelligent, beautifully written text that betrays its author’s intimate relationship with

language. And it is a wonderful debut which proves that Issa Quincy has closely observed the

world and promises that he will continue to find new and care-filled ways of presenting it.

KANYIN AJAYI is a stage director, writer, and scholar with a PhD in Comparative Literature. She recently translated and directed Marie NDiaye’s play Rien d’humain and has published short fiction in Angel Food.